The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1851.

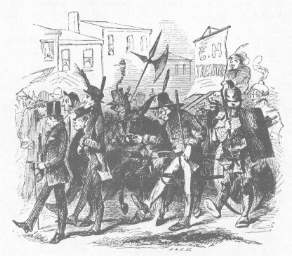

MAY 28th.—The custom-house, at the corner of Montgomery and California streets, having been destroyed by the fire of the 4th instant, another building was speedily fitted up for the same purposes at the corner of Kearny and Washington streets. The treasure, amounting to upwards of a million of dollars, had been preserved in a large safe (which had escaped damage from the fire) in the old building. To-day the removal of this treasure to the new custom-house took place; and the manner of doing so created some little excitement and much laughter in the town, from the excessive care and military display which the collector thought fit to adopt on the occasion. Some thirty gigantic, thick-bearded fellows, who were armed with carbines, revolvers and sabres, surrounded the cars containing the specie, while the Honorable T. Butler King stood aloft on a pile of ruins with a huge “Colt” in one hand and a bludgeon in the other, marshalling his men and money “the way that they should go.” The extraordinary procession proceeded slowly along Montgomery street to the new custom-house, Mr. King, marching, like a proud drum-major, at the head of his miniature grand army. The people, meanwhile, looked on with astonishment, and with some grief, that their city should be considered so lawless and wicked a place as to require so formidable a force even to guard millions of treasure in broad daylight, and along one or two of the principal streets, where there were continually present thousands of the most respectable inhabitants. But immediately the farcical nature of the whole exhibition struck the most phlegmatic, and peals of laughter and cries of ironical applause accompanied the brave defenders of “Uncle Sam’s” interests to the end of their perilous march. It was felt that there was but one thing wanted to make the show complete—half-a-dozen great guns from the presidio.

In

the absence of other matters of local importance, this bloodless achievement

formed the subject of a humorous song, composed by a young man of the town,

and which he sang in one or more of the public saloons, on many occasions,

“with much applause.” The thing had a run, and served to fill the clever

author’s purse. He had a large number of copies lithographed, on which

was a caricature print of the procession, and these he disposed of at a

dollar apiece. In a single night he sold five hundred copies at this rate.

As the tune to which the song was set was a popular and easy one, soon

the town rang with the story of “The King’s Campaign.” But besides this

effusion, there immediately appeared innumerable paragraphs, squibs, jests,

good sayings in social circles and the public journals. It is one of the

penalties which people must pay for their superiority in place over their

neighbors that their actions are pretty severely criticised, and, when

occasion serves, ridiculed. It was so here “with a will,” and to Collector

King’s great mortification. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

But kings and collectors have potent remedies for the many evils that beset

them. Frank Ball, the writer of the song in question, was shortly afterwards

sent for by the collector, and favored with a private interview. Ordinary

men might have “beat about the bush,” or employed a friend in the little

transaction which followed; but the Hon. T. Butler King, with the same

dauntless face which he showed on occasion of the treasure removal, bluntly

began conversation with the anxious poet, by asking whether he would not

like to have a desirable post in the customs. Mr. Ball, gasping with surprise,

mumbled, “Yes, surely!” “Then, Sir, it is yours,” said the

collector, gravely. In gratitude Mr. Ball could do no less than stop singing

his famous song, which was doubtless what his honorable and doughty chief

expected. Cerberus was sopped. This anecdote would be incomplete unless

we told that certain underlings attached to the custom-house, struck with

a new light, began forthwith to chant the obnoxious stanzas. Unluckily

they had mistaken the game, for the fact reaching the ears of the collector,

one of them, caught in the act, was instantly, though quietly, dismissed

from the service. It was a pretty illustration of the fable of “The Man,

the Spaniel, and the Ass.”

In

the absence of other matters of local importance, this bloodless achievement

formed the subject of a humorous song, composed by a young man of the town,

and which he sang in one or more of the public saloons, on many occasions,

“with much applause.” The thing had a run, and served to fill the clever

author’s purse. He had a large number of copies lithographed, on which

was a caricature print of the procession, and these he disposed of at a

dollar apiece. In a single night he sold five hundred copies at this rate.

As the tune to which the song was set was a popular and easy one, soon

the town rang with the story of “The King’s Campaign.” But besides this

effusion, there immediately appeared innumerable paragraphs, squibs, jests,

good sayings in social circles and the public journals. It is one of the

penalties which people must pay for their superiority in place over their

neighbors that their actions are pretty severely criticised, and, when

occasion serves, ridiculed. It was so here “with a will,” and to Collector

King’s great mortification. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

But kings and collectors have potent remedies for the many evils that beset

them. Frank Ball, the writer of the song in question, was shortly afterwards

sent for by the collector, and favored with a private interview. Ordinary

men might have “beat about the bush,” or employed a friend in the little

transaction which followed; but the Hon. T. Butler King, with the same

dauntless face which he showed on occasion of the treasure removal, bluntly

began conversation with the anxious poet, by asking whether he would not

like to have a desirable post in the customs. Mr. Ball, gasping with surprise,

mumbled, “Yes, surely!” “Then, Sir, it is yours,” said the

collector, gravely. In gratitude Mr. Ball could do no less than stop singing

his famous song, which was doubtless what his honorable and doughty chief

expected. Cerberus was sopped. This anecdote would be incomplete unless

we told that certain underlings attached to the custom-house, struck with

a new light, began forthwith to chant the obnoxious stanzas. Unluckily

they had mistaken the game, for the fact reaching the ears of the collector,

one of them, caught in the act, was instantly, though quietly, dismissed

from the service. It was a pretty illustration of the fable of “The Man,

the Spaniel, and the Ass.”

There are so many serious matters—murders, suicides, larcenies, grand and petty burglaries, assaults, fires, and the dismal-like in these “Annals,” that we are glad, and so too may the reader be, to have an opportunity such as this of introducing a facetious subject, which once delighted the San Franciscans. We, therefore, give an illustration of the caricature above alluded to, and the song itself:—

“THE KING’S CAMPAIGN; OR, REMOVAL OF THE DEPOSITS.

“Come, listen a minute, a song I’ll sing,

Which I rather calculate will bring

Much glory, and all that sort of thing,

On the head of our brave Collector King.

Ri tu di nu, Ri tu di nu,

Ri tu di nu di na.

“Our well-beloved President

This famous politician sent,

Though I guess we could our money have spent

Without aid from the general government.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“In process of time this hero bold

Had collected lots of silver and gold,

Which he stuck away in a spacious hole,

Except what little his officers stole.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“But there came a terrible fire one night,

Which put his place in an awful plight,

And ‘twould have been a heart-rending sight,

If the money had not been all right.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“Then he put his officers on the ground,

And told ‘em the specie vault to surround,

And if any ‘Sydney Cove’ came round,

To pick up a cudgel and knock him down.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“But the money had to be moved away,

So he summoned his fighting men one day,

And fixed ‘em all in marching array,

Like a lot of mules hitched on to a dray.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“Then he mounted a brick and made a speech,

And unto them this way did preach,—

‘Oh, feller-sogers, I beseech

You to keep this cash from the people’s reach.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“‘For,’ said he, ‘ ’well convinced I am,

That the people’s honesty’s all a sham,

And that no one here is worth a d—n,

But the officers of Uncle Sam.’

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“Then he drew his revolver, and told ‘em to start,

But he sure to keep their eyes on the cart,

And not to be at all faint of heart,

But to tread right up, and try to look smart.

Ri tu di nu, &c.

“Then each man grasped his sword and gun,

The babies squalled and the women run,

And all agreed that the King was one

Of the greatest warriors under the sun.

Ri tu di nu, Ri tu di nu,

Ri tu di nu di na.”

They were a wild, perverse race, the San Franciscans in those days, taking much delight in whatever mortified the “city fathers.” They are immoderately fond of fun and devilment still; and any thing of a peculiar spicy nature,—from a simple fall in the mud, or the kissing of a pretty girl, up to the five thousand dollar bribe of a senator, or a municipal papa, or grand-papa being caught lurking about the premises of a jealous married man, flies like lightning, or their own great fires over the whole city. The people live so much together in hotels and boarding-houses, they meet so frequently for talk and drink (in vino veritas) at bars and billiard-rooms, that every piece of scandal or matter of public interest is sure to ooze out and be discussed in all its bearings. A dozen daily papers by hint, inuendo, broad allusion, and description, considerably assist the promulgation and spreading of idle tales. Hence, they often assumed an importance which other communities may think they scarcely deserve. The year of which we write, 1851, had a full share of such local and temporary facetioe, some of which may appear worthy of record, if it were only to illustrate the times. The affairs of the aldermen’s salaries and the curious medal business were both prolific subjects for jesting and outrageous merriment. Dr. D. G. Robinson, a proprietor of the Dramatic Museum, gained considerable popularity by a series of doggerel, “random rhymes” which he gave on his own stage, in which almost every municipal man of mark was hit off, and sometimes pretty hardly too. So highly were these verses relished, and so much favor did the author gain thereby with the people, that Dr. Robinson was triumphantly returned as alderman to fill a vacancy which had occurred in the first board. He was afterwards seriously named as likely to be the most popular candidate for the mayoralty in 1852. Such rewards do the generous citizens bestow upon those who amuse them. Dr. Robinson’s rhymes were subsequently collected into a small printed pamphlet, which will no doubt possess much interest to such as still relish the gossip and scandal of the day. It would be out of place to give here any characteristic quotations from the work. People look back already with surprise to the favorable notoriety which these songs gained for their author, and more especially to the elevated position to which they were the means of raising him. We have narrated the absurd affair of the removal of the treasure, and given the relative song, only because they were reckoned rather important events of the time, and concerning which there was much public merriment for a long period afterwards. The parties interested can now well afford to laugh heartily at the whole business. These things, also, form one illustration of the state of society and “life” in San Francisco at the date of their occurrence.

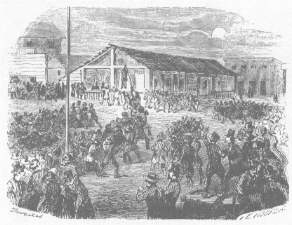

JUNE 3d.—For some time back the attempts of incendiaries to fire the city seem to be increasing. Cases of this nature are occurring daily, where the suspicious circumstances are evident, but where unfortunately the really guilty party cannot be detected. It is extremely difficult to discover criminals in the very act of committing arson. Incendiaries do their deeds only in dark and secret corners, and if interrupted, they have always ready a dozen trifling excuses for their appearance and behavior. The train and the slow match can be laid almost any where unobserved, while the “foul fiend” quietly steals away in safety. The inhabitants had got nervously sensitive to the slightest alarm of fire, and were greatly enraged against the presumed incendiaries. This day one Benjamin Lewis underwent a primary examination on the charge of arson. As the evidence was being taken, the Recorder’s Court began to fill, and much excitement to spread among the people. At this time, a cry of “fire!” was raised, and great confusion took place in the court-room, people rushing desperately out and in to learn particulars. This was a false alarm. It was believed to be only a ruse to enable the prisoner’s friends to rescue him from the hands of justice. The latter was therefore removed for safety to another place. Meanwhile, some three or four thousand persons had collected outside of the building, who began to get furious, continually uttering loud cries of “Lynch the villain! Hang the fire-raising wretch! Bring him out—no mercy—no law delays! Hang him—hang him!” Colonel Stevenson harangued the crowd in strong language, encouraging the violent feelings that had been excited against the prisoner. Mayor Brenham endeavored to calm the enraged multitude. Loud calls were at length made for “Brannan,” to which that gentleman quickly responded, and advised that the prisoner should be given in charge to the “volunteer police,” which had been recently formed. A motion to this effect was put and unanimously carried. But when the prisoner was looked for, it was found that the regular police had meanwhile carried him out of the way—nobody knew, or would tell where. Perforce the crowd was obliged to be satisfied, and late in the afternoon it gradually dispersed.

This is one instance of the scenes of popular excitement which were now of frequent occurrence in the city. Repeated losses by fire, and the terrible array of unpunished, undetected, triumphant crime, were turning the inhabitants absolutely savage against the supposed criminals. Matters were coming fast to a head, which was immediately to ripen into the “Vigilance Committee.” All these popular “demonstrations” were ineffectual in deterring the “Sydney coves,” and those of a like character, from the commission of the most reckless, wanton, and flagrant outrages. Incendiary attempts were now remarked almost daily. Not only the desire for plunder, but malice against individuals, and an unnatural lust for general destruction, seemed to inspire the villains.

In regard to the particular case of Lewis, it may be mentioned that the grand jury found a true bill against him for arson. Twice shortly afterwards was he brought before the District Criminal Court for trial, and on each occasion his counsel found a “flaw” in the indictment, which quashed the proceedings. These delays and defects in the law were working the suffering people up to madness. This is only one case, but it may be taken as a fair specimen of the general inefficiency of the judicial officers and tribunals in punishing crime. The grand juries were continually making formal complaints that their presentments were disregarded, and that criminals were somehow never convicted and punished, while generally their trials were so long delayed that the prisoners either escaped from confinement, or the essential witnesses in the case had gone nobody knew whither; and so the prosecutions failed. San Francisco was truly in a desperate condition at this period of its history. Though few arrests were made in proportion to the number of offences actually committed, yet it may be mentioned, that, to take one instance, on Monday morning, the 9th June of this year, there were thirty-six cases before the Recorder’s Criminal Court from one district alone (the second), out of the eight composing the city. “ Of the whole,” we quote from a journal of the time, “six were for drunkenness, six for fighting, six for larceny, three for stabbing, one for burglary, four for fast riding, four for assaulting officers, three for keeping disorderly houses, one for an attempt at robbery,” &c. Yet the previous day, Sunday, on which these offences had been committed, had been remarked by the press as having been unusually quiet and decently observed—without any noise or crime worth noticing.

Of this date an ordinance was passed by the council boards, and approved of by the mayor, granting to Mr. Arzo D. Merrifield and his assigns, the privilege of introducing fresh water by pipes into the city. It had happened at the various fires that the numerous public water reservoirs were either wholly or partially empty; and great difficulty was at all times experienced in filling them. This reason, as well as the desire to have an abundant supply of pure, fresh water for household purposes, had long led parties to consider the best means of bringing it into the city by pipes from a distance. Various schemes were talked of among the public, and discussed in the journals. The plan of Mr. Merrifield to bring water from a small lagoon, called the “Mountain Lake,” situated about four miles west of the plaza, and which was well supplied by springs, was at length approved of by the common council, and under the ordinance noticed the projector became entitled to certain privileges for the term of twenty-five years, upon condition of his plans being carried into effect. Mr. Merrifield, his associates and assigns, were authorized to break open the streets, and lay down water-pipes in the same, upon properly filling up and replacing the openings. The quantity of water to be provided in a general reservoir, and the amount of discharge by pipes, were both fixed; while provision was made for the amount of rates to be paid by the citizens using the water, which rates were to be adjusted by a board of commissioners to be chosen annually by the common council. At the end of twenty-five years, from and after the 1st day of January, 1853, the entire water-works were to be deeded to the city, in consideration of the privileges and benefits that might accrue to the projector and his assigns and associates during the said term of years. The corporate authorities were also to be entitled to the gratuitous use of the water for the purpose of extinguishing fires, and for hospital and other purposes. In terms of this act, Mr. Merrifield granted a bond for fifty thousand dollars that the works should be completed on or before the 1st of January, 1853.

The gentleman named having conveyed his privileges to a joint-stock company, called the “Mountain Lake Water Company,” another ordinance was, of date 14th of July, 1852, passed and approved of, whereby the former one was amended to the following effect, viz.: That the new company should only be entitled to the privileges granted by the first ordinance for the term of twenty years:—that the board of commissioners to fix the rates payable by those who used the water should be chosen, three by the common council, and two by the Mountain Lake Water Company, under the regulations specified in the ordinance:—that the term within which the works should be completed should be extended to the 1st of January, 1854, provided the Water Company should expend fifty thousand dollars on the works within six months of the date of the ordinance, and at least a similar sum every six months thereafter until the said last mentioned date:—that the privileges granted to the said Water Company should be exclusive for the term of five years after 1st of January, 1853 ;—and, lastly, that the said ordinance should expire at such time after the 1st day of January, 1855, as the said Water Company should refuse, or be unable, to supply the city, at such elevation as the common council should fix, “one million of gallons of pure and wholesome fresh water during every twenty-four hours.”

JUNE 11th.—The “Vigilance Committee” is at last formed, and in good

working order. They hanged at two o’clock this morning upon the plaza one

Jenkins, for stealing a safe. For the particulars of the trial and execution,

we refer the reader to a subsequent chapter, where also will be found an

account of the other doings of this celebrated association.