The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1851.

JUNE 22d.—The sixth great fire. It began a few minutes before eleven o’clock in the morning, in a frame house situated on the north side of Pacific street, close to Powell street. The high winds which usually set in about this hour from the ocean during the summer season, speedily fanned the flames, and drove them south and east. All day they spread from street to street, consuming one building-square after another. The water reservoirs happened to be nearly empty, and even where the firemen had water enough for the engines, their exertions were of little use in stopping the conflagration. Nor was it much better with the hook and ladder companies, whose useful operations were thwarted by the owners of the property they were seeking to pull down for the common good. Subsequent inquiries seemed to show that the fire must have been raised by incendiaries, while several attempts were detected during the day to kindle various distant quarters of the town, yet untouched by the flames. The fire extended from Powell nearly to Sansome street, and from Clay street to Broadway. Within these limits ten entire squares were destroyed, and large parts of six others. The total damage was estimated at three millions of dollars. Happily the chief business portion of the town escaped, and which had suffered so severely six or seven weeks before. In the fire of the 4th May, every newspaper establishment in the city, except that of the “Alta California,” was totally destroyed. In the fire of the 22d instant, all escaped, except that of the journal named. These conflagrations made no distinctions of persons or properties; but with a wild justice, sooner or later, reduced all to the same level. The proprietors of the Alta now lost their building, presses, types, paper and office furniture, just as their brethren of the broad sheet were ruined before. The City Hall, located at the corner of Kearny and Pacific streets, which had been originally erected at an immense expense as a hotel, and was purchased more than a year before by the corporation for one hundred and fifty thousand dollars, and improved at a heavy cost, was totally consumed, although the principal office records were saved. Mr. Thomas Maguire, the proprietor of the “Jenny Lind Theatre,” on the plaza, which was a most valuable building, now lost all again,—a sixth time, by fire! But it is needless to particularize losses, where every citizen may be said to have been burned out several times, and to have again and again lost his all. With a sigh or a laugh, according to the temperament of the sufferer, he just began once more to raise his house, stock it with new goods, and arrange his future plans. The indefatigable spider was at work again.

Many of the buildings erected since these last fires show a wonderful improvement in strength and grandeur. When the work was to be done it was now well done; and it is believed that if any buildings can possibly be made fire proof in the most trying circumstances, many have now been made so in San Francisco. Solid brick walls, two and three feet in thickness, double shutters and doors of malleable iron, with a space two feet wide between them, and huge tanks of water, that could flood the whole building from roof to cellar, seem to defy the ravages of the fiercest future conflagration. Of that substantial character are many of the banking establishments, the principal stores and merchants’ offices, and the most important houses in the city. This improved style of building has chiefly been rendered necessary by the great conflagrations we have had occasion to notice. Of the different companies formed for extinguishing fires we treat in a subsequent chapter. It is believed that they form the most complete and efficient organization of their kind in the world.

The

six great fires successively destroyed nearly all the old buildings

and land-marks of Yerba Buena. We extract the following pleasantly

written lamentation on this subject from the “Alta California” of 21st

September, 1851:— “The fires of May and June of the present year, swept

away nearly all the relics of the olden time in the heart of the city.

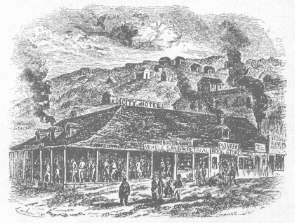

The old City Hotel [corner of Kearny and Clay streets], so well known and

remembered by old Californians, after standing unscathed through three

fatal fires, fell at the fourth. How many memories cling around that old

building! It was the first hotel started in San Francisco, then the village

of Yerba Buena, in the year 1846. When the mines were first discovered,

and San Francisco was literally overflowing with gold, it was the great

gaming head-quarters. Thousands and thousands of dollars were there staked

on the turn of a single card, and scenes such as never were before, and

never again will be witnessed, were exhibited in that old building during

the years 1848 and 1849. In the spring of ‘49, the building was leased

out at sixteen thousand dollars per annum, cut up into small stores

and rooms, and underleased at an enormous profit. Newer and handsomer buildings

were erected and opened as hotels, and the old ‘City’ became neglected,

deserted, forgotten: then it burned down, and this relic of the olden time

of San Francisco was among the things that were. Then the old adobe custom-house

that had been first built for that purpose, and then used as a guard-house

and military office by the Americans, and then afterwards as the American

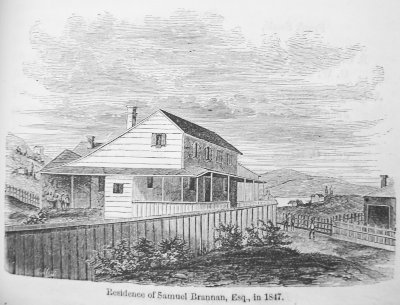

custom-house, was also burned. The wooden building directly back of it,

with the portico, was also one of the old buildings—erected and occupied

by Samuel Brannan, Esq. in 1847. [In this house were exhibited the first

specimens of gold brought from the placeres.] This also was burned,

and all that remains of 1847, in the vicinity of the plaza, is the old

adobe on Dupont street. This building, in the latter part of ‘47 and ‘48

was occupied by Robert A. Parker as a large trading establishment. This

has stood through all the fires, and it is hoped that it may remain for

years as a relic of the past.” That hope was vain. In the following year

the adobe on Dupont street was pulled down to make way for finer houses

on its site. So has it been with all the relics of six or eight years’

standing. What the fires left, the progress of improvement swept from the

ground.

The

six great fires successively destroyed nearly all the old buildings

and land-marks of Yerba Buena. We extract the following pleasantly

written lamentation on this subject from the “Alta California” of 21st

September, 1851:— “The fires of May and June of the present year, swept

away nearly all the relics of the olden time in the heart of the city.

The old City Hotel [corner of Kearny and Clay streets], so well known and

remembered by old Californians, after standing unscathed through three

fatal fires, fell at the fourth. How many memories cling around that old

building! It was the first hotel started in San Francisco, then the village

of Yerba Buena, in the year 1846. When the mines were first discovered,

and San Francisco was literally overflowing with gold, it was the great

gaming head-quarters. Thousands and thousands of dollars were there staked

on the turn of a single card, and scenes such as never were before, and

never again will be witnessed, were exhibited in that old building during

the years 1848 and 1849. In the spring of ‘49, the building was leased

out at sixteen thousand dollars per annum, cut up into small stores

and rooms, and underleased at an enormous profit. Newer and handsomer buildings

were erected and opened as hotels, and the old ‘City’ became neglected,

deserted, forgotten: then it burned down, and this relic of the olden time

of San Francisco was among the things that were. Then the old adobe custom-house

that had been first built for that purpose, and then used as a guard-house

and military office by the Americans, and then afterwards as the American

custom-house, was also burned. The wooden building directly back of it,

with the portico, was also one of the old buildings—erected and occupied

by Samuel Brannan, Esq. in 1847. [In this house were exhibited the first

specimens of gold brought from the placeres.] This also was burned,

and all that remains of 1847, in the vicinity of the plaza, is the old

adobe on Dupont street. This building, in the latter part of ‘47 and ‘48

was occupied by Robert A. Parker as a large trading establishment. This

has stood through all the fires, and it is hoped that it may remain for

years as a relic of the past.” That hope was vain. In the following year

the adobe on Dupont street was pulled down to make way for finer houses

on its site. So has it been with all the relics of six or eight years’

standing. What the fires left, the progress of improvement swept from the

ground.

JULY 11th.—Trial and execution of James Stuart.

AUGUST 24th.—Recapture from the legal authorities of Whittaker and McKenzie, and their execution by the “Vigilance Committee.”

SEPTEMBER 3d.—Annual election for the County of San Francisco. The following were the officials chosen: —

Senate.

Frank Soulé,

Jacob R. Snyder.

Assembly.

B. Orrick,

A. C. Peachy,

A. J. Ellis,

H. Wohler

G. W. Tenbroeck,

R. N. Wood.

Isaac N. Thorne.

Judge of the Superior Court.

John Satterlee.

County Judge.

Alexander Campbell.

Sheriff.

John C. Hayes.

County Clerk.

James E. Wainwright.

County Recorder.

Thomas B. Russum.

District Attorney.

H. H. Byrne.

County Treasurer.

Joseph Shannon.

County Surveyor.

C. Humphries.

Coroner.

Nathaniel Gray.

County Assessor.

Henry Vandeveer.

Harbor Master.

George Simpton.

The new city charter had provided that the first general election for municipal officers should be held on the fourth Monday of April, 1851, and “thereafter annually at the general election for State officers.” Under this section of the charter it was understood by some that the second city election should take place in September of the year named, when the usual annual election of State officers occurred. Another construction was put upon the section in question by the parties already in office and by a large number of the inhabitants, to the effect that the second election under the charter could only take place in September, 1852. Thus one party would give the existing common council and municipal officers only half a year in power, while another party, including the present incumbents, claimed a year and a half.

So dignified, or so satisfied with the legal strength of their position, were the existing city officers, that they took no steps to order a new election in September, 1851. Their opponents, however, relying on their own interpretation of the words of the charter, proceeded to act without them, and, unopposed in any way, elected the whole parties on their ticket. The general public took little interest in the matter, and most people seemed to believe that the new election would end in nothing. So little did the citizens concern themselves, that some of those newly elected, polled but a very few votes. When the election was finished the new officers made a demand upon the old ones for a surrender of the public books and documents. This being refused, the new mayor elect, Stephen R. Harris, immediately raised the necessary legal action against the old mayor, C. J. Brenham, for a declaration of his own rights and the ejection of the latter from office. In the district court a judgment was given to the effect that the present incumbents should hold office till April, 1852, and that then those elected in September, 1851, should enter upon and remain in office for one year. The result of this decision would have been that six months would always intervene between the election and the entering upon office of the municipal authorities. This decision was unsatisfactory to most people. Mr. Harris next carried the case into the supreme court, where a majority of the judges (24th December), after able arguments were heard from the parties, reversed the judgment of the court below, and found Mr. Harris entitled to enter upon office as in September, 1851. Mr. Brenham promptly acknowledged the weakness of his position, and at once yielded to his legal successor. Party feeling prevented the other city officers from surrendering their seats so readily. Those already in power consisted of men of both of the great political parties—whig and democratic; and had been originally selected chiefly from among the independent candidates, as men who would earnestly work for the common good and the purification of the city from official corruption and wide-spread crime. On the other hand, those newly elected were altogether of the democratic party. The old council offered to resign, if the new one would do the same; when both could appeal a second time to the poople. But the latter council refused to do this. Meanwhile, the legal courts had adjourned, and it would have cost much time and expense to drive out the old council from the places which they persisted in retaining; and their year of office would probably expire before this could be managed. In the end, however, the old council thought it best for their own honor and the interests of the city, to quietly retire from the unseemly contest, and make way for their unexpected successors. The names and offices of the latter were as follows.—

Mayor.—Stephen R. Harris.

Recorder.—George W. Baker.

Marshal.—David W. Thompson.

Street Commissioner.—Theodore Payne.

Comptroller.—Jas. W. Stillman.

Treasurer.—Smyth Clarke.

Tax Collector.—D. S. Linell.

City Attorney.—Chas. M. Delaney.

Recorder’s Clerk.—Thomas W. Harper.

City Assessors.—James C. Callaghan, David Hoag, Arthur Matthews.

Aldermen.

E. L. Morgan,

Wm. G. Wood,

Jos. H. Blood,

John Cotter,

Caleb Hyatt,

James Grant,

N. S. Pettit,

Wm. Moore.

Assistant Aldermen.

Henry Meiggs,

Jos. Galloway,

W. H. Crowell,

N. Holland,

D. W. Lockwood,

James Graves,

J. C. Piercy,

John W. Kessling.

SEPTEMBER 16th.—The “Vigilance Committee” agreed to suspend indefinitely farther operations regarding crime and criminals in the city. The old extensive chambers in Battery street were relinquished, and new rooms, “open at all times, day and night, to the members,” were taken in Middleton and Smiley’s buildings, corner of Sansome and Sacramento streets. During the three preceding months this association had been indefatigable in collecting evidence and bringing the guilty to justice. It had been formed not to supersede the legal authorities, but to strengthen them when weak; not to oppose the law, but to sanction and confirm it. The members were mostly respectable citizens, who had, and could have, only one object in view—the general good of the community. They exercised an unceasing vigilance over the hidden movements of the suspected and criminal population of the place, and unweariedly traced crime to its source, where they sought to stop it. They had hanged four men without observing ordinary legal forms, but the persons were fairly tried and found guilty, while three, at least, of the number, confessed to the most monstrous crimes, and admitted death to be only a due punishment. At this small cost of bloodshed, the “Vigilance Committee” freed the city and country of many reckless villains, who had been long a terror to society. When these had disappeared, outrages against person and property almost disappeared too, or were confined to petty cases. The legal and municipal authorities now acquired, what previously they lacked, sufficient power to master the remaining criminals; and the committee, having no longer a reason for continued action, gladly relinquished the powers they had formerly exercised. Grand juries, instead of offering presentments against them, only praised in the usual reports their useful exertions, while, like all good citizens, they lamented their necessity. Judges occasionally took offence at the terms of such reports, and sought to have them modified; but the grand juries were firm. Judge Levi Parsons applied to the Supreme Court to have certain obnoxious sentences in one of these reports struck out; but his petition was refused. People felt that there was much truth in the repeated declarations of the grand juries, and they hailed with delight their expressions of implied confidence in the Vigilance Committee. The weak, inefficient, and sometimes corrupt courts of law were denounced as strongly by the juries as by that association itself. In one report the grand jury said:—“The facilities with which the most notorious culprits are enabled to obtain bail, which, if not entirely worthless, is rarely enforced when forfeited, and the numerous cases in which by the potent influence of money, and the ingenious and unscrupulous appliance of legal technicalities, the most abandoned criminals have been enabled to escape a deserved punishment, meets with their unqualified disapprobation.”

But the worst days were over, and comparative peace was restored to society. Therefore the Vigilance Committee ceased to act. The members, however, did not dissolve the association, but only appointed a special or executive committee of forty-five to exercise a general watchfulness, and to summon together the whole body when occasion should require. This was shortly afterwards done in one or two instances, when instead of being opposed to the authorities, the members now firmly supported them by active personal aid against commotions and threatened outrages among the populace. They had originally organized themselves to protect the city from arson, murder and rapine, when perpetrated as part of a general system of violence and plunder by hardened criminals. In ordinary crimes, and when these stood alone, and did not necessarily lead to general destruction, the Vigilance Committee did not interfere farther than as good citizens and to merely aid the ordinary officials whose duty it was to attend to all cases of crime. When, therefore, some six months later, a body of two thousand excited people sought to “lynch” the captain and mate of the ship Challenge for cruelty to the crew during the passage from New York to San Francisco, the Vigilance Committee, instead of taking the side of the enraged multitude, firmly supported the legal authorities. On many occasions, both before and after this time, the committee were of great service to the authorities. At their own cost, they collected evidence, apprehended criminals and delivered them into the hands of legal justice. When the city offered a reward of $2500 to any person who would give information which might lead to the apprehension and conviction of an incendiary, the committee offered a reward of $5000 for the same services. The members gave large contributions to hasten the completion of the public jail; and, in many ways, by money, counsel and moral aid, and active personal assistance, sought earnestly to raise the character of the judicial tribunals and strengthen their action. There could not be a greater calumny uttered against high-minded men than to represent, as was frequently done in other countries, and in the Atlantic States, the members of the Vigilance Committee as a lawless mob, who made passion their sole guide and their own absolute will the law of the land. Necessity formed the committee, and gave it both irresistible moral and physical force. One might as well blame a drowning wretch for clinging to a sinking brother, or to a straw, as say that the inhabitants of San Francisco did wrong—some in joining the association, and others in not resisting but applauding its proceedings. People out of California could know little at best of the peculiar state of society existing there; and such as condemned the action of the Vigilance Committee positively either knew nothing on the subject, or they outraged the plainest principles of self-preservation. We all defend the man who, with his own hand, violently and unscrupulously slays the midnight robber and assassin, because he would otherwise lose his own life and property, and where the time and place make it ridiculous to call for legal protection. So also should we defend the community that acts in a similar manner under analogous circumstances. Their will and power form new ex tempore laws, and if the motives be good and the result good, it is not very material what the means are. This subject is treated at greater length in the chapter on the Vigilance Committee, and to it the reader is referred.

OCTOBER 3d.—”Wells & Co.” bankers, suspended payment. This and the bankruptcy of H. M. Naglee already noticed, are the only instances of failure among that class of the citizens of San Francisco. When the place and the speculative spirit of the people are borne in mind, it is high testimony to the general stability of the banking interest, that only two of their establishments have become bankrupt.

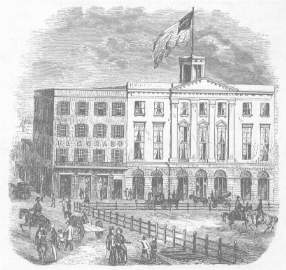

OCTOBER

4th.—Opening of the new Jenny Lind Theatre on the Plaza. This was a large

and handsome house. The interior was fitted up with exquisite taste; and

altogether in size, beauty and comfort, it rivalled the most noted theatres

in the Atlantic States. It could seat comfortably upwards of two thousand

persons. The opening night presented a brilliant display of beauty and

fashion, and every part of the immense building was crowded to excess.

A poetical address was delivered on the occasion by Mrs. E. Woodward. A

new era in theatricals was now begun in San Francisco; and since that period

the city has never wanted one or two first class theatres and excellent

stock companies, among which “stars” of the first magnitude annually make

their appearance. Before this date there had been various dramatic companies

in San Francisco, but not before had there been so magnificent a stage

for their performances. The “Jenny Lind” did not long remain a theatre.

The following year it was purchased by the town for a City Hall for the

enormous sum of two hundred thousand dollars. The external stone walls

were allowed to stand, but the whole interior was removed and fitted up

anew for the special purposes to which it was meant to be applied.

OCTOBER

4th.—Opening of the new Jenny Lind Theatre on the Plaza. This was a large

and handsome house. The interior was fitted up with exquisite taste; and

altogether in size, beauty and comfort, it rivalled the most noted theatres

in the Atlantic States. It could seat comfortably upwards of two thousand

persons. The opening night presented a brilliant display of beauty and

fashion, and every part of the immense building was crowded to excess.

A poetical address was delivered on the occasion by Mrs. E. Woodward. A

new era in theatricals was now begun in San Francisco; and since that period

the city has never wanted one or two first class theatres and excellent

stock companies, among which “stars” of the first magnitude annually make

their appearance. Before this date there had been various dramatic companies

in San Francisco, but not before had there been so magnificent a stage

for their performances. The “Jenny Lind” did not long remain a theatre.

The following year it was purchased by the town for a City Hall for the

enormous sum of two hundred thousand dollars. The external stone walls

were allowed to stand, but the whole interior was removed and fitted up

anew for the special purposes to which it was meant to be applied.

OCTOBER 20th.—The “American” theatre opened. This was a large brick and wooden house in Sansome street, between California and Sacramento streets. It could contain nearly two thousand persons, and was very elegantly furnished inside. Mrs. Stark gave the opening address. The walls sank nearly two inches on the opening night, when the “house” was densely crowded. The site formed a portion of the bay, and the sand which made the artificial foundation had been deposited upon a bed of soft yielding mud. Considerable fears were entertained in such circumstances for the safety of the structure. Happily the sinking of the walls was regular, and after the first night no material change was perceptible.

OCTOBER 31st.—To enable the distant reader to form an idea of the crowded

state of the harbor, and which it may be mentioned was at all times about

as well filled, we give the following accurate list of the number of vessels

lying there at this date, viz:—

| Ships. | Barques. | Brigs. | Schooners. | Ocean Steamers. | Total. | |

| American | 42 | 64 | 67 | 50 | 9 | 232 |

| British | 5 | 23 | 5 | 3 | 36 | |

| French | 9 | 1 | 1 | 11 | ||

| Chilian | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 sloop & 1 galliot | 6 | |

| Bremen | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 10 | |

| Austrian | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Swedish | 3 | 3 | ||||

| German | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Italian | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Dutch | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Storeships | 148 | |||||

| Total number of vessels | 451 |

The store-ships had originally belonged to all nations, though chiefly to America. In 1848 and 1849, most of the vessels that then arrived in the bay were deserted by their crews, while both in these years and in 1850, many old and unseaworthy vessels had been hurriedly pressed into the vast emigration service to CalIfornia. A considerable number of all these vessels were not worth the expense of manning and removing, and so they were left to be used as stores and lodging-houses in the suddenly thronged town, or to rot and sink, dismantled and forsaken. We have had occasion at various places to mention that several of these ships are now lying on dry land, in the very centre of the city.

NOVEMBER 6th.—A grand ball was given in the evening of this day at the Parker House, by the Monumental Fire Company. It was one of the finest affairs of the kind held in the city. Upwards of five hundred ladies and gentlemen were present. Such balls were becoming too numerous to be all chronicled, while amidst the general brilliancy it is difficult to select any one as a specimen to show forth the times.

DECEMBER.—The southern portion of the State, having been recently in great danger from attacks of the confederated Indian tribes, applied for aid to Gen. Hitchcock, commanding U. S. forces in California. He accordingly sent as many of his troops as could be spared, and authorized the raising of two companies of mounted volunteers. Great excitement, in consequence of this permission and the previous alarming news, existed in the city, and numbers hastened to enroll themselves in the proposed companies. To the disappointment of many applicants, a selection only could be received. The two companies were placed under the respective commands of Col. John W. Geary and Capt. Daniel Aldrich, while Col. J. C. Hayes was appointed to the command in chief. Later intelligence from the south, to the effect that the Indian difficulties were being arranged, rendered it unnecessary for the volunteers to proceed thither.

DECEMBER 21t.—This day was remarkable for an unusually severe storm of wind and rain, which continued during the night, and lasted several days without abatement. The tide was several feet higher than ordinary, and the swell from the bay rolled in so heavily as to wash away the sand from many of the newly-piled water lots. Several vessels dragged from their moorings and came in collision with others. Store-ships, that had long been imbedded in the sand, were set afloat and drifted to other quarers. The water at Jackson street rose so high as to cross Montgomery street, causing, at their junction, a lake of no inconsiderable dimensions. The cellars in the lower part of the city were inundated.