The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

THE Mission of San Francisco, as mentioned in the first part of this work, was founded in the year 1776. It was situated about two and a half miles to the south-west of the Cove of Yerba Buena. Besides the mission buildings, there were erected, at the same time, a presidio and fort, along the margin of the Golden Gate, the former being distant from the mission about four miles, and from the cove nearly the same space. The latter was situated about a mile nearer the ocean than the presidio, close upon the sea-beach, and on a rocky height at the narrowest point of the strait.

Before 1835, the village of Yerba Buena had neither name nor existence. The Mexican Government had some time before resolved to found a town upon the cove of that name, which was reputed the best site on the shores of the Bay of San Francisco for establishing a port. Much discussion and litigation, involving immense pecuniary interests, have occurred as to the date and precise character of the foundation of Yerba Buena. It has long been matter of keen dispute whether the place was what is called a Spanish or Mexican “pueblo;” and although, after previous contrary decisions, it was assumed (not being exactly decided upon evidence) by the Supreme Court to be a “pueblo,” the subject seems to be still open to challenge. It is unnecessary in this work to do more than merely allude to the question. In the year last above mentioned, General Figueroa, then governor of the Californias, passed an ordinance, forbidding the commandant of the presidio of San Francisco to make any grants of land around the Yerba Buena Cove nearer than two hundred varas (about one hundred and eighty-five yards) from the beach, without a special order from the governor, the excluded portion being intended to be reserved for government uses. Before any steps could be taken for the survey and laying out of the proposed town, General Figueroa died; and the place was neglected for some years, and left to proceed as chance and individuals would have it. There had been previous applications for grants of the whole land around the cove for professedly farming purposes, which circumstance led to the governor’s passing the temporary ordinance, lest, some time or another, the portion of ground intended to be reserved should, through accident or neglect, be granted away.

Captain W. A. Richardson was appointed the first harbormaster, in the year 1835, and, the same year, he erected the first house, or description of dwelling, in the place. It was simply a large tent, supported on four red-wood posts, and covered with a ship’s foresail. The captain’s occupation in those days seems to have been the management of two schooners, one belonging to the Mission of San Francisco, and the other to the Mission of Santa Clara. These schooners were employed in bringing produce from the various missions and farms around the bay to the sea-going vessels which lay in Yerba Buena Cove. The amount of freight which the captain received was twelve cents a hide, and one dollar for each bag of tallow. The tallow was melted down and run into hide-bags, which averaged five hundred pounds each. For grain, the freight was twenty-five cents a fanega (two and a half English bushels).

Some years before this period, Yerba Buena Cove had been occasionally approached by various ships of war and other vessels. For many years, the Russians had continued to pay it annual visits for supplies of meat and small quantities of grain. One of their vessels took away annually about one hundred and eighty or two hundred tons of such provisions. In 1816, the English sloop of war “Racoon” entered the port; also, in 1827, the “Blossom,” of the same nation, on a surveying cruise. In the last named year, the French frigate “Artemesia,” of sixty guns, arrived. In 1839, there appeared the English surveying ships, the “Sulphur” and the “Starling.” In 1841, the first American war vessel, the “San Luis,” sloop, arrived; and, later in the same year, the “Vincennes,” also American, on a surveying expedition. In 1842, came the “Yorktown,” the “Cyane,” and the “Dale,” all of the American navy; and in the same year, the “Brillante,” a French sloop-of-war. From this last named year downwards both ships of war and merchantmen of all nations occasionally entered the port. Whale ships first began to make their appearance for supplies in the fall of the year 1822, increasing in number, year by year, since that period. However, some impolitic port restrictions by the authorities had the effect latterly of sending off a considerable number of this class of ships to the Sandwich Islands, a place much less convenient for obtaining supplies than San Francisco Bay. Since likewise the discovery of gold in the country, and the consequent temptation of seamen to desert, as well as the enhanced price of most supplies, whale ships have not found it their interest to visit San Francisco, but prefer victualling and refitting at the Sandwich Islands.

Previous to 1822, a small traffic was carried on between the coast of Mexico and the California ports; the latter exporting principally tallow and a little soap. Some small vessels from the Sandwich Islands also visited occasionally San Francisco and the other harbors in California. It was in the last year named that the trade began between California and the United States and England. The country then sent its tallow chiefly to Callao and Peru, and its hides to the States and to England. The price of a hide in 1822, was fifty cents, and of tallow, six dollars per hundred weight. These prices had the effect of soon decreasing the number of cattle; and, in the following year, hides rose to one and a half dollars apiece, payable in cash, or two dollars, if the amount was taken in merchandise. The trade value of hides continued at nearly this rate until the war between the United States and Mexico.

Some few natural occurrences during these early years of the place are worth recording. In December 1824 and in the spring of the following year, very heavy rains fell over all this part of the country. The Sacramento and tributaries rose to a great height, and their valleys were flooded in many places to a depth of fourteen feet. It was partly owing to the great volumes of fresh water brought down through the bay, in 1825, that a portion of the land at the southern side of the entrance, was washed away as stated in a previous chapter. In September, 1829, several very severe shocks of an earthquake were experienced in San Francisco, which forced open lock-fast doors and windows. In 1839, an equally severe earthquake took place. In 1812, however, a much more serious convulsion had been felt over all California, which shook down houses and some churches in several parts of the country, and killed a considerable number of human beings. The Church of San Juan Capistrano was completely destroyed, and forty-one persons, chiefly Indians, were killed by its fall. We have already said that an Indian tradition attributes the formation of the present entrance to the Bay of San Francisco to an earthquake, which forced open a great passage through the coast range of hills for the interior waters. It may be mentioned, when on this subject, that since these dates, no serious occurrences of this nature have happened at San Francisco; though almost every year slight shocks, and occasionally smarter ones have been felt. God help the city if any great catastrophe of this nature should ever take place! Her huge granite and brick palaces, of four, five and six stories in height, would indeed make a prodigious crash, more ruinous both to life and property than even the dreadful fires of 1849, 1850 and 1851. This is the greatest, if not the only possible obstacle of consequence to the growing prosperity of the city, though even such a lamentable event as the total destruction of half the place, like another Quito or Caraccas, would speedily be remedied by the indomitable energy and persevering industry of the American character. Such a terrible calamity, however, as the one imagined, may never take place. So “sufficient for the day is the evil thereof.” This maxim abundantly satisfies the excitement-craving, money-seeking, luxurious-living, reckless, heaven-earth-and-hell-daring citizens of San Francisco.

We have elsewhere explained the nature of the climate in respect that the winter and summer months are simply the rainy and dry seasons of the year. We have seen above, the effects of excessive rains; and we may also mark the result of unusual drought. In the personal recollections of Captain Richardson, who is our authority on this subject, there have been several such seasons in the country around the Bay of San Francisco since 1822, when that gentleman came to California. The grass on such occasions was completely dried up, and cattle perished in consequence. The missionaries were under the necessity of sending out all their Indian servants to cut down branches of oak trees for the herds to subsist upon. In these dryer seasons, too, the crops suffered greatly from grasshoppers; which insects, about the month of July, when the corn was still green, would sweep all before them. It may be remarked generally, that while the year is divided into two seasons—wet and dry—there is great irregularity, in the case of the former, as to the average quantity of rain falling annually. During some winters heavy rains pour down, without intermission, for months together; while, on other and often alternate winters, the sky is clear for weeks—then for only a few days slight showers will descend—and again there occurs a long period of the most delightful and dry weather imaginable. Slight frosts are occasionally felt during the winter months; and ice, from the thickness of a cent to that of an inch is seen for a day or two, nearly every season. Generally, however, the winter climate is mild and open, and the winter months are the most pleasant of the year.

The excessively and injuriously wet and dry seasons are exceptional cases, and do not impugn the accuracy of the statements, made elsewhere, of the general mildness of the climate, productiveness of the soil, and safety of the harvest. A fertile field or a fruitful tree will not lose its character, because occasionally there happens to be a short crop. The Pacific is still reputed a serene ocean, though sometimes a gale or tempest sweeps over it. Even in the case of possible earthquakes, nobody would hold France, or Spain, or even Italy—the bella Italia of the old world, as California is of the new one—to be dangerous countries to live in, although historical records show that much damage has been done in them, at long intervals, by volcanic eruptions and subterranean movements.

In

May, 1836, Mr. Jacob Primer Leese arrived in the Cove of Yerba Buena, with

the intention of establishing a mercantile business at San Francisco, in

partnership with Mr. Nathan Spear and Mr. W. S. Hinckley, who were to remain

at Monterey, and manage the business of the firm there. Mr. Leese brought

letters from the then governor of California, Don Mariano Chico, to the

alcalde and commandante of San Francisco, desiring them to render him all

assistance in their power in arranging a location and otherwise. Mr. Leese

at once fixed on the beach of Yerba Buena Cove for his establishment, but

as the ordinance of General Figueroa, concerning the government reserve,

was still in force, he could not procure an allotment nearer the beach

than at the distance of two hundred varas. The alcalde and commandante

were much pleased that Mr. Leese should come to settle among their people,

and at once offered him a choice of two locations, one being at the mouth

of Mission Creek, and the other at the entrance to the bay near the presidio.

Mr. Leese, however, had made up his mind on the subject; and, partly for

his own business convenience, and probably, in part, foreseeing the increased

future value of sites around Yerba Buena Cove, would accept no grant but

one in that quarter. In this the local authorities could not legally aid

him; so Mr. Leese returned forthwith to Monterey with his story and complaint

to Governor Chico. On explanations there, the governor informed Mr. Leese

that he would instruct the alcalde of San Francisco to grant an allotment

within the limits of the government reserve, and in the mean time authorized

Mr. Leese to select for himself the most convenient place he could find

elsewhere.

In

May, 1836, Mr. Jacob Primer Leese arrived in the Cove of Yerba Buena, with

the intention of establishing a mercantile business at San Francisco, in

partnership with Mr. Nathan Spear and Mr. W. S. Hinckley, who were to remain

at Monterey, and manage the business of the firm there. Mr. Leese brought

letters from the then governor of California, Don Mariano Chico, to the

alcalde and commandante of San Francisco, desiring them to render him all

assistance in their power in arranging a location and otherwise. Mr. Leese

at once fixed on the beach of Yerba Buena Cove for his establishment, but

as the ordinance of General Figueroa, concerning the government reserve,

was still in force, he could not procure an allotment nearer the beach

than at the distance of two hundred varas. The alcalde and commandante

were much pleased that Mr. Leese should come to settle among their people,

and at once offered him a choice of two locations, one being at the mouth

of Mission Creek, and the other at the entrance to the bay near the presidio.

Mr. Leese, however, had made up his mind on the subject; and, partly for

his own business convenience, and probably, in part, foreseeing the increased

future value of sites around Yerba Buena Cove, would accept no grant but

one in that quarter. In this the local authorities could not legally aid

him; so Mr. Leese returned forthwith to Monterey with his story and complaint

to Governor Chico. On explanations there, the governor informed Mr. Leese

that he would instruct the alcalde of San Francisco to grant an allotment

within the limits of the government reserve, and in the mean time authorized

Mr. Leese to select for himself the most convenient place he could find

elsewhere.

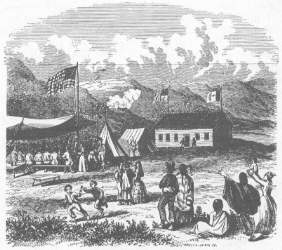

Back to Yerba Buena Cove hastened Mr. Leese, and on the first of July presented to the alcalde his new letters. On the following day he landed boards and other materials for building, and immediately took possession of a one-hundred vara lot, adjoining on the south side that on which Captain Richardson’s tent was already erected. Mr. Leese’s lot was situated about two hundred or two hundred and fifty yards from the beach, and is the spot where the St. Francis Hotel was subsequently erected, at the corner of Clay and Dupont streets. Mr. Leese was indefatigable in hastening the erection of his dwelling, which was finished by ten o’clock on the morning of the 4th of July—the first glorious fourth—when the independence of America was commemorated in style in California. These two houses, belonging to Capt. Richardson and Mr. Leese, were the earliest houses erected in Yerba Buena, and formed the beginning of the City of San Francisco. It is but eighteen years since their erection, and now there is a population of over fifty thousand around the spot!

While Mr. Leese was erecting his mansion, which seems to have been rather a grand structure, being made of frame, sixty feet long and twenty-five feet broad, Captain Richardson was kindly proceeding across the bay to Sonoma, where he invited all the principal folks of the quarter to a banquet in the new building. Two events—each great in their way—were to be celebrated: first, Independence Day, and next, the arrival of Mr. Leese in the country, his welcome and house-warming. The two worthy souls, cordially fraternizing, were determined to make a great affair of it; and so indeed it happened. As it was the first grand scene in the future San Francisco, where there have since been so many, we are tempted to dwell a little on the eventful occasion. Future generations will pleasantly reflect on this auspicious commencement to the pride of the Pacific, then like a new-born infant cradled by its tender parents, Capt. Richardson and Mr. Leese, and tricked out in all the magnificence of an heir’s baby clothes.

At this time there was lying in the cove the American barque “Don Quixote,” commanded by Mr. Leese’s partner, Capt. Hinckley, and on board of which were their goods. There were also at anchor in the port another American ship and a Mexican brig. These vessels supplied every bit of colored bunting they could furnish, with which was decorated Mr. Leese’s hall. A splendid display was the result. Outside of the building floated amicably the Mexican and American flags—the first time the latter was displayed on the shore of Yerba Buena. Captain Hinckley seems to have been somewhat extravagant in his passion for sweet sounds, since he always travelled with a band of music in his train. Through this cause the most stylish orchestra, perhaps, ever before heard in California, was provided by him. This consisted of a clarionet, flute, violin, drum, fife and bugle; besides two small six pounders to form the bass, and to add their emphatic roar to the swelling din, when a toast of more than usual importance should be given. These last, however, were borrowed from the presidio.

The

feast was prepared; the minstrels were met; and the guests began to assemble

about three o’clock on the afternoon of the Fourth. They were about sixty

in number, and included General M. G. Vallejo and all the principal families

from the neighborhood of Sonoma, such as the Castro, Martinez, &c.,

as well as the chief inhabitants of San Francisco. Besides the banqueting

hall, Mr. Leese had erected a number of small tents, in which to receive

his numerous guests and provide for them comfortably. At five o’clock dinner

was served, and immediately afterwards followed the toasts. First of all

was given the union of the Mexican and American flags. (How little did

the convivial parties then dream of the near advent of the sole and absolute

sway of the Americans in the country!) General Vallejo next paid the honors

to Washington. Then followed appropriate national and individual toasts

in their order; but which it is needless to particularize. The guests were

as happy as mortals could well be; and, in short, “all went merry as a

marriage bell.” The abundance and variety of liquors at table seemed to

tickle the Californians amazingly. One worthy gentleman took a prodigious

fancy to lemon syrup, a tumbler full of which he would quaff to every toast.

This soon made him sick, and sent him off with a colic; which was all matter

of mirth to his “jolly companions, every one.” At ten o’clock our “city

fathers” got the table cleared for further action, and dancing and other

amusements then commenced. The ball was kept hot and rolling incessantly,

all that night, and it appears, too, the following day; for, as Mr. Leese

naively observes, in his interesting and amusing diary, “our fourth

ended on the evening of the fifth.” Many of the simple-minded Indians

and such lower class white people as were not invited, had gathered around

while the festivities and sports were going on among the people of quality,

and could not contain themselves for joy, but continually exclaimed, “Que

buenos son los Americanos! “—What capital fellows these Americans are!

And doubtless the white gentry thought, and often said the same.

The

feast was prepared; the minstrels were met; and the guests began to assemble

about three o’clock on the afternoon of the Fourth. They were about sixty

in number, and included General M. G. Vallejo and all the principal families

from the neighborhood of Sonoma, such as the Castro, Martinez, &c.,

as well as the chief inhabitants of San Francisco. Besides the banqueting

hall, Mr. Leese had erected a number of small tents, in which to receive

his numerous guests and provide for them comfortably. At five o’clock dinner

was served, and immediately afterwards followed the toasts. First of all

was given the union of the Mexican and American flags. (How little did

the convivial parties then dream of the near advent of the sole and absolute

sway of the Americans in the country!) General Vallejo next paid the honors

to Washington. Then followed appropriate national and individual toasts

in their order; but which it is needless to particularize. The guests were

as happy as mortals could well be; and, in short, “all went merry as a

marriage bell.” The abundance and variety of liquors at table seemed to

tickle the Californians amazingly. One worthy gentleman took a prodigious

fancy to lemon syrup, a tumbler full of which he would quaff to every toast.

This soon made him sick, and sent him off with a colic; which was all matter

of mirth to his “jolly companions, every one.” At ten o’clock our “city

fathers” got the table cleared for further action, and dancing and other

amusements then commenced. The ball was kept hot and rolling incessantly,

all that night, and it appears, too, the following day; for, as Mr. Leese

naively observes, in his interesting and amusing diary, “our fourth

ended on the evening of the fifth.” Many of the simple-minded Indians

and such lower class white people as were not invited, had gathered around

while the festivities and sports were going on among the people of quality,

and could not contain themselves for joy, but continually exclaimed, “Que

buenos son los Americanos! “—What capital fellows these Americans are!

And doubtless the white gentry thought, and often said the same.

But let a Yankee alone for knowing his own interest in spending money lavishly! In a few days afterwards, Mr. Leese had concluded the landing of his twelve thousand dollars worth of goods, when he opened his store for business. The grateful guests, and all the people around, at once flocked to purchase; and trade, he says, became quite brisk, at most satisfactory prices.

Shortly after this event, Mr. Leese, upon a hasty courtship—or rather, for he seems to have had no time to wait, and California was beginning to shake off her lethargy and be a go-ahead country; in fact, none beyond “popping the question,” in smart business fashion, on the 1st of April, 1837 (ominous day for such a deed!)—was married to a sister of General Vallejo. On the 7th of the same month they were tied together, for life, by the “holy bands of matrimony;” and from this union, on the 15th of April, 1838, sprung their eldest child—ROSALIE REESE—being the first born in Yerba Buena.

In this year, Mr. Leese erected a large frame building on the beach, with consent of the alcalde, the latter observing that the governor had informed him he was going to lay out a few town lots. He therefore permitted Mr. Leese, in order to forward his plans, to take a one-hundred vara lot provisionally where he wished. The present banking-house of Mr. James King of William, at the corner of Commercial and Montgomery streets, and which is situated in what may be called the centre of San Francisco, occupies the site of Mr. Leese’s frame building on the beach of Yerba Buena Cove. In this year also, Captain Richardson erected an adobe building on the same lot he had always occupied, and which has been already noticed. This adobe building, one and a half stories high, was the old “Casa Grande” which stood on the west side of Dupont-street, between Washington and Clay streets, and was taken down in 1852. About this time, some native Californians and a few visitors of foreign extraction, chiefly American, began to settle in the rising town. The arrivals of ships likewise were gradually increasing.

In 1839, Don J. B. Alvarado, then constitutional governor of California, dispatched an order to the then alcalde of San Francisco, Francisco Haro, to get a survey taken of the plain and cove of Yerba Buena. This was accordingly made by Captain Juan Vioget in the fall of the same year, and was the first regular survey of the place. It included those portions of the present city which lie between Pacific street on the north, Sacramento street on the south, Dupont street on the west, and Montgomery street on the east. The original bounds of the new town were therefore very limited. The lot on which Mr. Leese built his second house was marked No. 1 on the plan, and its eastern front made the line of the present Montgomery street, which then formed the beach of the cove. Mr. Leese seems to have been pretty well treated by the authorities in the matter of the new town, since he appears to have received, besides the allotment already mentioned, farther grants of three one-hundred vara lots on the west side of Dupont street, and two on the south side of Sacramento street, as well as of other three lots, likewise outside of the survey. To conclude this notice of Mr. Leese’s close connection with the rising fortunes of Yerba Buena, it may be mentioned, that, in the month of August, 1841, he sold his dwelling-house to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and removed his property and family to Sonoma, with the intention of engaging in extensive cattle transactions in Oregon, which territory was then attracting much notice, and had begun to draw to it many agricultural settlers.