The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1852.

JUNE.—It appears from records kept by the late harbor master, Captain King, that seventy-four vessels claiming and entitled to be called “clipper ships,” and averaging rather more than 1000 tons burden, had arrived in tbe port of San Francisco during the last three years. These records commence with the well known brig Col. Fremont, in May, 1849, and include the Aramingo, which arrived in May, 1852. The average passage was one hundred and twenty-five days. Some of the fleet, however, made much more speedy voyages. The Flying Cloud, which arrived in August, 1851, performed the distance from New York in eighty-nine days. The Sword Fish, also from New York, arrived in February, 1852, after a passage of ninety days. The Surprise, arriving in March, 1851, the Sea Witch, in July, 1850,—both from New York,—and the Flying Fish, in February, 1852, from Boston, respectively accomplished the voyage in ninety-six, ninety-seven, and ninety-eight days.

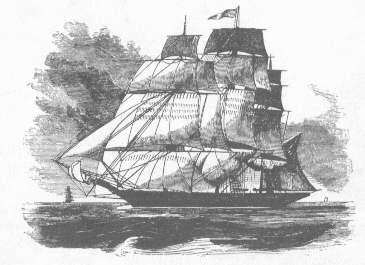

The

“clipper ship” is virtually the creation of San Francisco. The necessity

of bearing merchandise as speedily as possible to so distant a market,

one too which was so liable to be suddenly overstocked by goods, early

forced merchants and ship-builders interested in the California trade to

invent new and superior models of vessels. Hence the modern clipper with

her great length, sharp lines of entrance and clearance, and flat bottom.

These magnificent vessels now perform the longest regular voyage known

in commerce, running along both coasts of the Americas, in about four months;

while the ordinary ships of older models used to take seven and eight months

to accomplish the same distance. The contrast is very striking between

the short, clumsy vessels, of a few hundred tons burden, which brought

the early European navigators to the coast of California, and the large

and beautifully lined marine palaces, often of two thousand tons, that

are now continually gliding through the Golden Gate. These are like the

white-winged masses of cloud that majestically soar upon the summer breeze.

In another part of this work we have given an illustration of the galleon,

or sea-going armed merchantman of Drake’s day; here we lay before the reader

a representation of one of the finest modern California traders, a clipper

ship bound for San Francisco. While these noble vessels have revolutionized,

in every maritime country, the model and style of long-voyage ships, they

have also introduced a much happier marine nomenclature. The old-fashioned,

humdrum Julias and Mary Anns, the Trusties and Actives

are fast disappearing. The very names of our modern clippers have poetry

and music in them, and convey a wonderful sense of swiftness. They confer

even dignity on the dry details of the “marine reporter,” where the simple

words shine like golden particles in the Californian miner’s sands.

The

“clipper ship” is virtually the creation of San Francisco. The necessity

of bearing merchandise as speedily as possible to so distant a market,

one too which was so liable to be suddenly overstocked by goods, early

forced merchants and ship-builders interested in the California trade to

invent new and superior models of vessels. Hence the modern clipper with

her great length, sharp lines of entrance and clearance, and flat bottom.

These magnificent vessels now perform the longest regular voyage known

in commerce, running along both coasts of the Americas, in about four months;

while the ordinary ships of older models used to take seven and eight months

to accomplish the same distance. The contrast is very striking between

the short, clumsy vessels, of a few hundred tons burden, which brought

the early European navigators to the coast of California, and the large

and beautifully lined marine palaces, often of two thousand tons, that

are now continually gliding through the Golden Gate. These are like the

white-winged masses of cloud that majestically soar upon the summer breeze.

In another part of this work we have given an illustration of the galleon,

or sea-going armed merchantman of Drake’s day; here we lay before the reader

a representation of one of the finest modern California traders, a clipper

ship bound for San Francisco. While these noble vessels have revolutionized,

in every maritime country, the model and style of long-voyage ships, they

have also introduced a much happier marine nomenclature. The old-fashioned,

humdrum Julias and Mary Anns, the Trusties and Actives

are fast disappearing. The very names of our modern clippers have poetry

and music in them, and convey a wonderful sense of swiftness. They confer

even dignity on the dry details of the “marine reporter,” where the simple

words shine like golden particles in the Californian miner’s sands.

San Francisco was certainly a wealthy city, yet the amount of taxation

laid upon it was enormous. We give here some statistics taken from official

documents, showing the amount of cash which had been paid by the citizens

during the year previous to this date.

| DIRECT TAXES. | |

| Amount collected from City Licenses, from June 1st, 1851, to May 31st, 1852, | $275,873 14 |

| Amount collected from City Taxes, between said dates, | 262,665 23 |

| $538,538 37 | |

| Amount collected from State and County Taxes, from May 18th, 1851, to May 18th, 1852, | $231,348 85 |

| Amount of direct taxes paid by the people of San Francisco during the past year, | $769,887 22 |

| INDIRECT TAXES. | |

| Duties collected at the Custom House for six months, ending Dec. 31st, 1851, | $1,012,128 94 |

| Duties collected for three months, ending March 31st, 1852, | 450,041 50 |

| Duties collected for the fourth quarter (estimated,) | 484,056 81 |

| For the year ending June 30th, 1852, | $1,946,227 25 |

| Direct Taxes, as above, | 769,887 22 |

| Amount in cash actually contributed by San Francisco for support of

City,

State, County and National Governments for one year, |

$2,716,114 47 |

These statistics show only the amount actually paid; but there were arrears of direct taxes which would certainly be recovered (since they were secured upon property), and which would swell the amount chargeable on the year to $1,053,773. Adding the last sum to the amount of custom-house duties, it will be seen that about three millions of dollars were drawn, as taxes, from San Francisco in one year. If the population be estimated at 30,000, this would show that the amount of local direct taxation was about $35 per head. In regard to the goods paying custom-house duties, it will be borne in mind that a fair proportion of the necessaries, and at least one-half of the luxuries used in the State were consumed in this city. If we estimate therefore the population of the former at quarter of a million, it may be supposed that the sum of at least, $300,000 was actually contributed in indirect taxation by the inhabitants of the latter. This is at the rate of $10 per head. Add this to the sum of $35 above mentioned; and it appears that the total amount of direct and indirect taxation for a single year upon each inhabitant, male or female, infant or adult, of San Francisco, was $45. This is an amount of taxation which few cities or countries can show. But besides these sums, the holders of city real estate were assessed in two-thirds of the expense of grading and planking the streets opposite their properties; while the general citizens voluntarily incurred a vast amount of additional expense, in the appointment of special police to guard particular localities, in the gratuitous services of firemen, in lighting, watering, cleansing and repairing the public streets, in opening drains and sewers, and in many other ways, the duty of attending to which naturally falls, in the cities of other lands, upon the municipal authorities.

JUNE 4th.—We have already had occasion to mention the unexpected manner in which the common council existing at this time managed to get into office. They never enjoyed the confidence of the people, by whom in reality they were not chosen. Perhaps on that very account, they were the more determined to neglect the public interests and attend solely to their own. Had Mayor Harris not continually been a thorn in their side, much additional mischief would have been perpetrated. Though this gentleman was on their ticket, and came into office in the same doubtful manner with themselves, there existed a marked difference in their public acts. Dr. Harris was a man of undoubted personal integrity, and possessed in a high degree the confidence and esteem of the citizens. By his care and faithfulness, the city was saved from many heavy burdens that would recklessly have been laid upon it by the common council of this year. One noted instance was his refusal to approve of the aldermen’s ordinance accepting the terms of the act of the Legislature which relinquished the State claims to the water lots, upon the city recognizing and confirming certain of the old obnoxious “Cotton Grants.”

The purchase of the new Jenny Lind Theatre and Parker House for the purposes of a City Hall was another of the common council jobs which excited very much angry discussion at the time, and which afforded interesting and amusing “matter” for the newspapers—(the “Jenny Lind Swindle,” or sometimes “Juggle,” they facetiously called it),—during half a year. The old City Hall having been destroyed in the fire of 22d June, 1851, the various municipal officials were compelled to get business chambers where they could, for which very high rents had to be paid. As the different public offices were now located in separate parts of the town, much inconvenience was experienced. This arrangement could only be temporary. The rents, which were somewhere about forty thousand dollars per annum, formed a heavy tax upon the public; while ground could be bought and a proper building erected by the city itself for about four or five times that amount. Several desirable sites could be had in the town on moderate terms, and responsible contractors were ready to undertake the construction of the proposed building at fixed rates, which would certainly have reduced the total cost below two hundred thousand dollars. In these circumstances, the common council, for reasons, as the saying is, best known to themselves, and in spite of the indignant cries of the citizens, and the general remonstrances of the press, determined,—in conjunction with the board of supervisors of the county, who were to pay half the cost,—to purchase the Jenny Lind Theatre, and convert it into the proposed City Hall. The purchase-money of the building as it stood was to be $200,000; while to remove all the inside walls, leaving only the outer ones standing, and to build up the interior anew, properly fitted up for municipal purposes, was believed to involve the expenditure of nearly half as much more. At the same time, it was supposed that the building when so altered would be only a miserable structure at the best. An ordinance authorizing the purchase was passed by large majorities in both council boards, and sent to the mayor for approval, which was refused. Notwithstanding, the common council, on the 4th June, re-adopted the obnoxious ordinance, and passed it by a constitutional and almost unanimous vote.

Meanwhile, the public wrath was growing very clamorous, the more so perhaps that it was impotent. On the evening of the 1st of June, one of the usual mass and indignation meetings was held on the plaza, where the proposed purchase was passionately denounced. Mr. William A. Dana presided on the occasion. This was one of the most stormy meetings that had ever been held in the city. Hon. David C. Broderick, who was in favor of the proposed purchase, attempted to make a speech for his cause, but the noise and reproaches of the meeting effectually put him down. Sundry squabbling and wordy sparring took place between Mr. Broderick and Dr. J. H. Gihon, who was on this occasion the people’s orator; and the meeting ended in hubbub, riot and confusion. Little cared the common council for such proceedings—the general ire—the mayor’s veto—the denunciations and ridicule of the press. The matter was carried finally into the Supreme Court, at the instance of some public-spirited citizens, and shortly afterwards a judgment was obtained recognizing the right of the city and the board of supervisors to make the purchase. This was forthwith done; and the contemplated alterations were speedily made on the building, although at a great expense. The whole affair was long a prolific subject for conversation and discussion, for ridicule and the imputation of corrupt motives. It served to glorify the council of this year, as the notorious aldermen’s salaries and medal pieces of business had immortalized a previous party of “city step-fathers.”

After the purchase was made and the alterations were completed, it was found that the new structure answered the purposes intended better than was at first anticipated. The situation is excellent. At the present time, however (1854), it is beginning to be discovered that the building is too small for the increased business of the city. Movements are now making to purchase additional business chambers elsewhere, or to include a portion of the adjoining Union Hotel into the municipal establishment. Doubtless, before many years pass, the whole of either that building, or of the El Dorado gambling-saloon on the other side, if not both, will be required for the necessary extension of the City Hall, unless indeed it be located in some altogether different quarter, and built anew.

JUNE 28th.—The “Placer Times and Transcript,” transferred from Sacramento, is first published in San Francisco, under the management of Messrs. Fitch, Pickering & Lawrence.

JULY 5th.—”Independence-day” falling upon Sunday, was celebrated the next day. This national festival has always been a grand affair in San Francisco; and on this occasion the citizens exceeded all their former efforts. Prominent in the procession of the day were large bands of foreigners, particularly of the French and the Chinese. The latter displayed numerous fanciful flags and specimens of the finest workmanship of their people. Their gongs, cymbals, wooden bowls or drums, and strange stringed instruments, made the air hideous with diabolical sounds. One wagon was filled with several Chinamen richly and showily dressed, who occupied themselves in continually firing off their national crackers. In the evening there was a brilliant display of fireworks on the plaza, where some fifteen thousand of the inhabitants had assembled to witness the exhibition.

JULY 11th.—The Herald newspaper is printed on coarse brown paper, such as is commonly used for envelopes and for wrapping packages. About this period, and during some months following, all the newspapers of the city were reduced to the same or to even worse descriptions of paper. Day by day, the old broad sheets were becoming narrower and coarser, while they assumed every color of the rainbow. The Alta for a long time was published on a small double sheet (which, however, was of a pretty fine quality), where the typographical matter on a page measured only about fourteen inches in length by ten in breadth. The market had suddenly and unexpectedly happened to be without supplies of proper printing paper; and many months elapsed before a sufficient stock could be procured. Of course prices of the material rose enormously.

AUGUST 2d.—A duel took place this day between the Hon. Edward Gilbert, senior editor of the Alta California and ex-representative of the State in the Lower House of Congress, and General J. W. Denver, State Senator from Trinity County. Gen. Denver having taken personal offence at certain observations which had appeared in the “Alta California,” regarding Governor Bigler’s government, published a letter, in which he animadverted strongly on the terms of these observations, and talked of the writer in objectionable language. Mr. Gilbert, the author of the original obnoxious articles, considered the general’s letter unjust and offensive to himself, and thereupon challenged that gentleman. A hostile interview accordingly took place at Oak Grove, near Sacramento. The weapons were rifles, and the distance forty paces. General Denver, it was said, possessed an unerring aim, while Mr. Gilbert scarcely knew how to hold his piece. At the first interchange of shots, the general fired deliberately aside; while Mr. Gilbert missed. The challenger, or his second, insisted on the fight being continued, more especially, perhaps, because the former had been recently in the habit of ridiculing bloodless duels. His antagonist now considered that it was time for him to protect himself; and, at the next shot, sent his ball through Mr. Gilbert’s body. The wounded man never spoke again, and in a few minutes expired. This termination of the duel excited great regret in San Francisco, where Mr. Gilbert had been much esteemed. A numerous company of the citizens assembled to pay the last respects to his remains, public institutions passed resolutions to the honor of the deceased, the shipping hung their flags at half mast, many public buildings and private houses were decorated with mourning draperies, and the newspapers appeared with black lines down their columns.

The custom of fighting duels was at the period of which we write, as it at present is, deplorably common among the higher class of people of San Francisco. These encounters are generally conducted in a manner which must appear, somewhat strange to the natives of other civilized countries. There is little delicate privacy observed on the occasion. On the contrary, the parties, or their immediate friends, invite all their acquaintances, who invite others to go and witness the proposed engagement. It is sometimes announced the day before in the newspapers—time, place, parties, weapons, and every particular of the ceremony being faithfully given. That no price is mentioned for the sight, seems the only thing that distinguishes the entertainment from a bull or bear fight. If two notable characters be announced to perform a duel, say at the mission, half the city flocks to the place, and, of course, the spectators are much disappointed should nobody be slain. If the bloody entertainment be advertised to “come off” say at Benicia or somewhere in Contra Costa, the steamers of the eventful morning are densely packed with those who prefer the excitement of a gladiatorial show to the dull pursuit of business, or loafing about the streets. The favorite weapons are navy revolvers. The antagonists stand back to back, walk five paces, turn suddenly round, and fire away at their leisure, till one or both are wounded or slain, or the barrels are all discharged. Sometimes rifles are preferred. With these deadly instruments many men can lodge the ball within a hair’s breadth of a given mark at forty paces off, which is the usual distance between the parties in a duel of this description.

We intended to have made Mr. Gilbert’s death a text, not only for enlarging upon the usual savage and public nature of the numerous duels which take place here, but also for some remarks upon the general carelessness of life among the people, and the frequency of sudden personal quarrels, when revolvers, bowie-knives and “slung shots” are unhesitatingly made use of. But we have at so many other places in this work had occasion to allude to these every-day characteristics of the inhabitants, that little more need be said here on the subject. In the earlier years,—that is, in 1849 and 1850,—fatal affrays were of very frequent occurrence in the streets, and in every place of public amusement. In the gambling saloons, pistols, loaded with ball, would every night be discharged by some hot-headed, revengeful, or drunken fellows. The crowd around were always liable to be wounded, if not killed, but notwithstanding, play at every table went briskly on, as if no danger of the kind existed. A momentary confusion and surprise might take place if anybody happened to be murdered in the room; but soon the excitement died away. Similar events often occurred at the bar, or on the steps of a hotel, in a low dance or drinking-house, or in the open street, and nobody was much surprised, though some of the parties were severely wounded or killed outright. It was their “destiny,” or their “luck.” Since the years last mentioned, quarrels of this description have become less common, though they are still numerous. There is a sad recklessness of conduct and carelessness of life among the people of California; and nearly all the inhabitants of San Francisco, whatever be their native country, or their original pacific disposition, share in the same hasty, wild character and feeling. The circumstances of the time, the place and people, soon create the necessity in the latest immigrant of thinking and acting like the older residents on this subject. It has always been a practice with a large proportion of the citizens, to carry loaded fire-arms or other deadly weapons concealed about their persons, this being, as it were, a part of their ordinary dress; while occasionally the rest of the inhabitants are compelled also to arm themselves like their neighbors. Of course, these arms are intended for defence against attacks by robbers, as well as to be used, when necessary, against those who would merely assault the person without meaning to steal. Such weapons are not generally produced, except in cases of extremity, or the place would soon be made desolate; while sometimes the fear of provoking their use, may keep the rowdy and the insolent rascal quiet. Yet the unhappy possession of these fatal instruments often gives rise, on occasions of sudden passion, to many lamentable consequences.

AUGUST 10th.—Funeral solemnities, on a great scale, took place this day, in commemoration of the death of Henry Clay. On this occasion political parties of all principles, the different associated bodies, native Americans and foreigners of every nation—in short, the whole inhabitants united to pay homage and respect to the memory of the celebrated statesman. The procession was the largest assemblage of respectable people ever seen in the city, and was distinguished as much for the evident heartfelt sorrow in the mourners, as for the pomp and melancholy splendor of the slow-moving train, which extended about a mile in length. The Merchants’ Exchange, the Custom House, El Dorado, Bella Union, City Hall, Marshal’s Office, and in fact all the public buildings and many private houses were clothed in black draperies, as if the very stones were to bewail the loss of a great man. The whole of Montgomery street was hung in black, the sombre-looking folds of the cloth being relieved at places by wreaths and ornaments of white. Portions of every other main street were decorated in the same elaborate and perhaps overfanciful manner. The various engine houses were likewise suitably arrayed. While the insensate walls thus wore the aspect of universal gloom, the people themselves were dressed according to the solemnity and grandeur of the occasion—the natives of every land appearing in the recognized national costume that expressed the deepest grief and mourning in the wearer. The tolling of great bells, the measured boom of the bass drum and the swelling wail of wind instruments turned the hearts of the people heavy and sorrowful A hundred low-hung flags drooped over the city, and numerous bands of music played dead marches. If mechanical means could inspire or strengthen genuine sorrow, it was so on this occasion. The procession moved through the principal streets till it reached the plaza. There, the orator of the day, Judge Hoffman, delivered an appropriate and eloquent address. The dead no longer heard his praises chanted; but the memory of his deeds, his fiery eloquence, and the numberless benefits conferred on his country and on the world, by the famous orator and statesman, will long gratefully fill the minds of American citizens.

The occasion was worthy of a grand display; and it was admitted by everybody, that the procession, the ceremonies and general mourning, were of the most novel, imposing, and splendid description that had ever been witnessed in San Francisco.