The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1853.

JANUARY.—We have taken occasion to notice in various parts of this work the progress of commerce in San Francisco. Year by year, the number of vessels visiting the harbor was increasing. We present here some statements on the subject, compiled from a table of statistics by Colonel Cost, of the naval office.

ARRIVALS AND CLEARANCES IN THE PORT OF SAN FRANCISCO DURING THE YEAR

1852.

| Arrivals. | Clearances. | |||||

| Nations. | Vessels. | Tons. | Nations. | Vessels. | Tons. | |

| American | 346 | 188,575 | American | 405 | 216,642 | |

| British | 225 | 74,931 | British | 196 | 76,270 | |

| French | 29 | 11,286 | French | 33 | 12,949 | |

| Chilian | 37 | 9,393 | Chilian | 25 | 6,444 | |

| Mexican | 41 | 5,279 | Mexican | 34 | 4,567 | |

| Danish | 12 | 2,215 | Danish | 10 | 1,959 | |

| Bremen | 11 | 3,132 | Bremen | 11 | 2,977 | |

| Norwegian | 4 | 1,100 | Norwegian | 2 | 576 | |

| Hamburg | 20 | 4,628 | Hamburg | 20 | 4,185 | |

| Dutch | 15 | 6,965 | Dutch | 5 | 1,523 | |

| Hawaiian | 28 | 3,562 | Hawaiian | 25 | 3,190 | |

| Peruvian | 14 | 2,024 | Peruvian | 8 | 1,599 | |

| Prussian | 2 | 960 | Prussian | 2 | 540 | |

| Swedish | 4 | 1,156 | Swedish | 5 | 1,700 | |

| Portuguese | 3 | 675 | Portuguese | 2 | 450 | |

| Brazilian | 1 | 738 | Brazilian | 1 | 728 | |

| Sardinian | 3 | 1,038 | Sardinian | 7 | 1,383 | |

| Austrian | 1 | 521 | Austrian | 1 | 300 | |

| Am. Coasters | 351 | 196,282 | Am. Coasters | 833 | 115,462 | |

| TOTAL | 1,147 | 514,460 | TOTAL | 1,625 | 453,444 | |

| In 1851, the

arrivals were |

847 | 245,678 | In 1851, the

clearances were |

1,315 | 422,043 | |

| Increase | 300 | 268,782 | Increase | 310 | 31,401 |

The shipments of gold dust during 1852 from San Francisco, as appears from the custom-house record of clearances, amounted in all to $46,599,044. Of this amount the value of $45,251,724 was cleared for Panama; $511,376, for San Juan; $482,596, for Hong Kong; and the remainder principally for various ports on the Pacific. Sums carried away by individuals are not included in the amounts mentioned.

JANUARY 25th.—Election of officers of the Mercantile Library Association. It had long been evident that such an association was much needed in San Francisco. In the absence of any thing like a home or domestic comfort, all classes seemed to be alike forced to frequent places of public recreation, and were exposed to the many degrading influences which drink, gambling, and still worse vices have upon the personal character. To withdraw youths in particular from the haunts of dissipation, and to give to persons of every age and occupation the means of mental improvement, and a suitable place for passing their leisure hours, were the great objects of the Mercantile Library Association. Public meetings were held, at which the purposes and advantages of the proposed institution were strongly urged by its benevolent projectors and patrons; and committees were formed to collect contributions of books and subscriptions from the general public. By these means a considerable deal of interest was excited on the subject, and liberal donations and subscriptions were procured. The following gentlemen were unanimously elected as the first officers

President.—David S. Turner.

Vice-President.—J. P. Haven.

Treasurer.—C. E. Bowers, Jr.

Recording Sec'y.—R. H. Stephen.

Corresponding Sec'y.—Dr. H. Gibbons.

Directors.—E. E. Dunbar, J. B. Crockett, D. H. Haskell and E.

P. Flint.

The rooms of the association, which were on the second floor of the California Exchange,—a central and most convenient locality,—were first opened on the evening of the 1st of March of this year. The largest apartment was elegantly fitted up as a reading and lecture room, and was abundantly supplied with local newspapers, and with some of the leading journals of the Eastern States, as well as with a choice selection of magazines and reviews. The library contained fifteen hundred volumes by the best authors, and was being constantly increased by donations and purchases. Only one year later, it numbered about three thousand volumes, comprising many of the best standard works in the English language, besides many valuable works in French, Spanish, German, &c.

This institution is of the most excellent character, and deserves the active support and well wishes of every liberal-minded citizen. It is the best substitute for a portion of the comforts of a home that can be provided in the present condition of San Francisco. Occasional lectures on interesting topics, literary and dramatic essays and readings, and frequent public debates on political and other subjects of the day, give variety and excitement to the ordinary business of the association. The pleasures and advantages of this institution have not hitherto been sufficiently understood, or sought by the people for whom they were intended; but it may be presumed that the intrinsic and growing merits of the association will in future excite more fruitful notice from all classes of the community. The terms of membership are very moderate, being an entrance fee of ten dollars (since reduced to five dollars, "for clerks and others in employ"), and a monthly payment of one dollar. A subscription of twenty-five dollars, and a monthly payment of one dollar, entitle the party to one share in the stock of the institution, and to the profits arising on the same. The library and reading rooms are open every day, from 9 o'clock A. M. to 10 o'clock P. M. For two hours after noon they are only open to ladies, and gentlemen accompanying ladies. The chambers of the association are now in the Court Block, Merchant street.

FEBRUARY 5th.—The claim of José Yves Limantour presented to the Board of Land Commissioners. San Francisco, which had survived the Leavenworth and Colton grants, the Peter Smith sales, and other legalized robberies and "squatters" without number, though it suffered terribly in the struggle, was now threatened by a claim, which if held valid, would turn over to a single individual one-half of its real estate, owned partly by the city itself, and partly by thousands of onerous and bona fide holders, who fancied their possessions were their own by the strongest legal titles. Limantour, who was a Frenchman by birth, and had been a trader along the coast, stated, that he had advanced, in the year 1843, to Manuel Micheltorrena, who was then Mexican Governor and Commandante-General of the Californias, considerable sums of money for the use of the departmental government of that country, at a period when it was impoverished. In return for this service, or as it is expressed in the deed itself, "in consideration of loans in merchandise and ready money which he has made to this government at different times" (somewhere about $4000), Limantour said that he had received a complete grant of certain large tracts of land in the neighborhood of Yerba Buena. The deed of conveyance and several relative papers have been produced to the Board of Commissioners, and appear at first sight regular and legal documents. The first seems to have been given at Los Angeles, the 27th day of February, 1843, and is signed by Micheltorrena. It conveys "the land contained from the line of the pueblo de la Yerba Buena, distant four hundred varas from the settlement house (casa fundadora) of Don William Richardson to the south-east, beginning on the beach at the north-east, and following it along its whole edge (margen), turning round the point of Rincon to the south-east, and following the bay as far as the mouth of the estuary of the mission, including the deposits of salt water, and following the valley (cañada) to the south-west, where the fresh water runs, passing to the north-west side, about two hundred varas from the mission to where it completes two leagues north-east and south-west to the Rincon, as represented by the plat (diseño) No. 1, which accompanies the Expediente.

"Second: Two leagues of land, more or less, beginning on the beach of the 'Estacada' at the ancient anchorage of the port of San Francisco, below the castle (castillo) following to the south-east, passing the "presidio" (military post)—following the road of the mission, and the line to the south-west as far as the beach which runs to the south from the port, taking the said beach to the north-west, turning round the Point Lobos, and following to the north-east, along the whole beach of the castle (castillo) two hundred varas, and following the beach as far as the 'Estacada,' where begins the plat (diseño) No. 2."

The tracts of land contained within the boundaries mentioned (which are vague and very unsatisfactorily given), comprise four square leagues, and include a great part of the most valuable portion of the city. It may also be mentioned here, that, in addition to these four square leagues, Señor Limantour likewise claimed the Islands of Alcatraz and Yerba Buena in the bay, and the whole group of the Farallones, which lie twenty or thirty miles off the Heads, and a tract of land, one square league in extent, situated opposite the Island of Los Angeles, at the westward of Racoon Straits. Besides these islands and square leagues, Limantour has also claimed before the Board of Land Commissioners still more extensive properties in various parts of the State, amounting in all to considerably more than a hundred square leagues of land. All other claims are a bagatelle to this.

These great claims seemed so ridiculous and untenable at first sight, that the press and individuals pecuniarily interested were generally disposed to think very lightly of them. That Limantour should have been so long silent as to his alleged rights was a very odd circumstance that generated suspicion all was not told. He had looked on during years when the property included in his grants was being transferred over and over again to new buyers, always rising in value at every sale, and had tacitly appeared to assent to the existing state of things. When the ground was worth many millions of dollars, and hundreds, if not thousands of individuals were pecuniarily interested in it, then Limantour first declared his pretensions. His claim seemed monstrous—to one half of the great City of San Francisco, with all its houses and improvements and future prosperity!—a claim that had been mysteriously concealed for eight or ten years! Pshaw! it could not be an honest, valid one. So folks said to themselves. As while we write the matter remains under judicial consideration,—though some years may pass before a judgment can be obtained,—we are prevented from examining minutely the nature both of the claim and the objections to it. We may only state generally that many believe the former is "false, fraudulent, or simulated;" while Gen. James Wilson, Limantour's attorney, says—" With a perfect knowledge of all the papers and documents in the case; a careful consideration of all the testimony taken, I am constrained to say, and I do most conscientiously say, that there is not, and in my firm belief there cannot possibly be, the slightest indicia of fraud in it, or in any way connected with it. 'Fraud is to be proved, not inferred."' In the pamphlet from which these quotations are made, and which was printed and published by order of Limantour, Gen. Wilson discusses Micheltorrena's alleged grant, and finds it abundantly proved. He thus settles his client's cause with a thunder-clap sentence, which must frighten the very souls of Limantour's "nimble adversaries:"—"Say that deed of grant is not valid! Never—NEVER! It cannot be so said without rushing roughshod and blindfold over all the facts in the case, and all the law and equity in Christendom." If proof and the Land Commissioners sanction Limantour's claim, there will be a day of reckoning and lament to many of our citizens, who have fondly imagined themselves the true proprietors of much valuable real estate. Then will be tried the truth and worth of the maxim—Justitia fiat, ruat Coelum.

FEBRUARY 16th.—Election of delegates from the different wards to a convention to revise the city charter. The following parties were elected: —

First Ward.—Henry Meigs, Edward McGowan, William Carr.

Second Ward.—F. L. Jones, James Gallagher, E. W. Graham.

Third Ward.—D. A. Magehan, Eugene Casserly, W. H. Martin.

Fourth Ward.—S. W. Holliday, C. S. Biden, J. R. Dunglisson.

Fifth Ward.—Louis R. Lull, T. D. Greene, F. O. Wakeman.

Sixth Ward.—James Grant, Henry Richardson, David Jobson.

Seventh Ward.—A. C. Wakeman, James Hagan, Henry Sharpe.

Eighth Ward.—Thomas Hayes, I. D. White, William Green.

These parties met on the 7th of March at the council chambers in the City Hall, and proceeded to discuss the provisions of the existing charter and the proposed alterations upon it. The charter, as revised, was afterwards submitted to the people at the annual election of municipal officers. Little interest seemed to be manifested on the subject, except by the inhabitants of the eighth ward, whose personal interests were particularly affected by the contemplated measure. Though rejected by six wards, it was, on the whole, approved of by a majority of votes. Subsequently it was laid before the Legislature, to be formally passed by it as a new charter of the city. At the date of writing this notice, that event has not taken place. It differs materially from the former charter, and the propriety of some of its declarations, particularly what may be called the "squatter" provisions, has been much disputed. In many other respects, it is a decided improvement upon the present charter.

FEBRUARY 22d.—The anniversary of the birth-day of Washington had been adopted on previous occasions as a fit time to celebrate the organization of the fire companies of the city. On this day, the third annual celebration took place. It was distinguished by the large attendance of the firemen, the splendor of the procession, the fineness of the weather, and the great number of citizens, who as sympathetic spectators participated in the festivities of the occasion. The firemen were dressed in the uniform of the different companie, and their engines and various apparatus were burnished as brightly and decorated as beautifully as hands could manage. Several bands of music formed part of the procession, while banners and devices of various kinds gave increased animation to the scene. The chief interest, however, of the exhibition lay in the appearance of the men themselves. These were of every class in the community, and were a fine athletic set of fellows. Their voluntary occupation was a good and grand one, and required much skill and courage, while it was pursued under circumstances involving great personal danger, and often much inconvenience and pecuniary loss to individuals, who, at the call of duty, cheerfully forsook their own private business to save the community from a terrible calamity. At the awful peal of the alarm-bell, no matter at what hour or place, or how occupied, the fireman rushed to his post, to drag and work his pet engine where most needed. At busy noon, he threw aside his cash-book and ledger; in the evening, he abruptly left the theatre, or other place of amusement; at midnight, he started from sleep, and only half-dressed, leaped and ran to his appointed quarters. A few minutes later, and the whole city might be in a blaze! This thought gave speed to his heels and strength to his arms. Scarcely had the first heavy strokes of the alarm-bell ceased to vibrate on the panic-stricken ear, when were heard the lighter, cheerful peals of the bells of the engines, as they were wheeled from their houses and hurried rapidly through the streets.

Fires in San Francisco used to be dreadful affairs, and no pen can adequately describe the terror, confusion and despair that spread far and wide when the wild cry was heard. The danger and horror of conflagration are now much lessened, partly by the increase of fire-proof brick buildings, and partly by the continually growing efficiency of the fire companies. Still the alarm of fire can never be listened to without many sad misgivings as to the possible result. The centre and business part of the city may now seem to be beyond the reach of total destruction or even of a serious loss; yet large districts lying around the fireproof nucleus may any day be altogether consumed, if it were not for the unflagging and desperate efforts of the unpaid, volunteer firemen. From the peculiar risk and circumstances attending conflagrations in San Francisco, these noble men have always had a difficult and dangerous task to perform. Their boldness, their alertness, energy, and unwearied perseverance in their praiseworthy calling, have been long celebrated in America; and, to this day, it is a high term of honor over the civilized world to belong to their body. Many foreigners are members of the different companies. Later in this year, some of the French inhabitants of the city formed themselves into a company by themselves, called the "Lafayette."

On the occasion of the anniversary of the Fire Department of this year, the procession alluded to moved through the principal streets, attended, admired, and cheered by a large concourse of people. Indeed the whole city seemed to have turned out en masse. The firemen then proceeded to the American Theatre, where an occasional address was delivered by Frank M. Pixley. The house was filled to overflowing, and presented a fine show. There was a large attendance of ladies in the boxes.

MARCH

6th.—The Pacific mail steamship Tennessee went ashore this morning

at Tagus Beach, in Bolinas Bay, about three or four miles north of the

Heads, at the entrance to the Bay of San Francisco. Dense fogs, which had

misled the captain as to the ship's position, were the cause of the vessel

striking the shore. These fogs are very prevalent along the coast, and

have often been the cause of serious shipwrecks. The Tennessee had about

six hundred passengers on board, one hundred of whom were women and children.

By happy chance, the ship went upon a small, sandy beach, on both sides

of which at a short distance were enormous cliffs, on which if the vessel

had struck she would have gone immediately to pieces, and probably most

of those on board would have perished. As it was, and the sea being smooth,

the passengers were all safely landed, as well as the mail-bags and express

matter. It was expected that the Tennessee would afterwards have been safely

towed off. The Goliah and the Thomas Hunt, steam-tugs, were sent to perform

that operation; but after some trials, it was found to be impracticable.

After removing therefore a considerable quantity of cargo, stores, &c.,

the vessel was abandoned, and shortly afterwards went to pieces.

MARCH

6th.—The Pacific mail steamship Tennessee went ashore this morning

at Tagus Beach, in Bolinas Bay, about three or four miles north of the

Heads, at the entrance to the Bay of San Francisco. Dense fogs, which had

misled the captain as to the ship's position, were the cause of the vessel

striking the shore. These fogs are very prevalent along the coast, and

have often been the cause of serious shipwrecks. The Tennessee had about

six hundred passengers on board, one hundred of whom were women and children.

By happy chance, the ship went upon a small, sandy beach, on both sides

of which at a short distance were enormous cliffs, on which if the vessel

had struck she would have gone immediately to pieces, and probably most

of those on board would have perished. As it was, and the sea being smooth,

the passengers were all safely landed, as well as the mail-bags and express

matter. It was expected that the Tennessee would afterwards have been safely

towed off. The Goliah and the Thomas Hunt, steam-tugs, were sent to perform

that operation; but after some trials, it was found to be impracticable.

After removing therefore a considerable quantity of cargo, stores, &c.,

the vessel was abandoned, and shortly afterwards went to pieces.

The loss of the Tennessee was the first known of a series of calamities at sea, which happened about this time, and in which San Francisco was deeply interested. The most terrible and disastrous of these was the loss of the steamship Independence, of Vanderbilt's Independent Line, from San Juan to San Francisco. Upon the morning of the 16th of February, about daybreak, and when the atmosphere was perfectly clear, the ship struck upon a sunken reef, about a mile from the shore of Margarita Island, off the coast of Lower California. The sea was quite smooth at the time. The engine was backed, and the ship hove off the reef. As she was making water rapidly, it was thought best to beach her. She was accordingly run ashore in a small cove on the south-west side of the island, about five miles distant from the place where she had first struck. At this time it was discovered that the vessel was on fire. The people, who had hitherto been quiet and self-possessed, now lost all control of themselves; and many in a frantic state leaped overboard. All order seemed to be lost, and everybody thought only how best to save himself. The scene is said to have been horrible in the extreme. The crew and passengers amounted to four hundred and fourteen persons; and of this number nearly two hundred perished, among whom were seventeen children and fifteen females. When intelligence of the sad occurrence reached San Francisco, it caused much excitement and general sorrow. Many had to mourn the loss of a relative or friend, whose coming had been fondly expected. Liberal contributions were made by the citizens to alleviate the sufferings of the surviving passengers of the Independence, and to carry them to a place of safety from the desolate and dangerous island upon which they were thrown, naked, and without food or shelter.

On the morning of the 9th April following, the steamship S. S. Lewis, of the Nicaragua line, went ashore at a place six miles north of Bolinas Bay, and about fifteen miles north of the Heads. Dense fogs were the cause of this loss, as they had been the cause of the loss of the Tennessee. There were three hundred and eighty-five persons on board when the ship struck, all of whom were saved, as well as the greatest part of their personal baggage. The sea was running high at the time, and soon afterwards the vessel went to pieces.

Thus were three of the large ocean steamers connected with San Francisco lost within little more than a month, two of which had gone ashore within the distance of a few miles from the city. It was remarked that there seemed to be a kind of fatality attending the passenger steamers connected with our port. Eleven vessels of that description, some of which were of a magnificent character, had been lost within the previous two years. The list is as follows: —

Commodore Preble.—May 3d, 1851, on Humboldt Bar.

Union.—July 5th, 1851, at San Quentin.

Chesapeake.—Rudder lost at sea, put into Port Oxford for repairs,

October 10th, 1851; proceeded to Humboldt, and was condemned and sold.

Sea Gull.—Jan. 26th, 1852, on Humboldt Bar.

General Warren.—Jan. 31st, 1852, Clatsop Spit.

North America.—Feb. 27th, 1852, forty miles south of Acapulco.

Pioneer.—Aug. 17th, 1852, San Simeon's Bay.

City of Pittsburg.—Oct. 24th, 1852, burned in the Bay of Valparaiso,

on her way to California.

Independence.—Feb. 16th, 1853, burned at Margarita Island.

Tennessee.—March 6th, 1853, entrance to San Francisco Bay.

Lewis.—April 9th, 1853, three miles north of Bolinas Bay.

APRIL.—For some months back the citizens have been much excited by the introduction and progress through the legislative chambers, of a bill to extend the water front of the city six hundred feet beyond the existing boundary line. It appears that the annual expenditure of the State was year by year greatly exceeding its income, and financial difficulties were the natural consequence. To procure some relief from these, Governor Bigler, in a message to the Senate and House of Assembly, recommended that the limits of San Francisco should be extended towards the water, and that such extension should be sold or leased for the benefit of the State. This counsel appeared most unjust, and caused much alarm to the inhabitants of the city. The mayor and the boards of aldermen and assistant aldermen severally issued messages and reports against the passage of the contemplated measure. The board of aldermen, on the 31st January, unanimously adopted a memorial to the Legislature, in which they represented that any measure of the nature suggested by the governor would be productive of incalculable hurt to the prosperity of San Francisco.

"Your memorialists," the document said, "have spared no labor to procure a full and frank expression of opinion by the most competent to decide upon the merits of the proposed extension, and have received the concurrent testimony of every captain and merchant in the city, that the sanction of your honorable body to such a proceeding would place in jeopardy the entire shipping of the port, by depriving it of the protection and shelter of the head lands which it at present enjoys.

“Your memorialists feel warranted in asserting, from their own observation, as well as from the assurance of the present distinguished officer in command of the Hydrographical Party of the United States Coast Survey, that the extent to which the present filling up of the City Front has been pushed, has worked material injury to the safe anchorage of vessels already, by shoaling the waters of the harbor, and compelling ships of heavy draft to anchor further out, exposed to the full force of the tide and the fury of the strong gales from the south-east that prevail during the rainy season.”

These opinions were fully shared in by the inhabitants generally. Not only would San Francisco, the commercial metropolis of the State, be materially damaged as a port, but much grievous wrong would be committed against the owners of property upon the line of the existing water front. By the Act of 26th March, 1851, which leased the State's interest in the water lots for ninety-nine years, and which specifically defined the boundary lines, it was declared that the same "shall be and remain a permanent water front" of the city. In the knowledge and faith of this constitutional and binding declaration, the water lots had been sold and improvements made upon them. The present owners had every reason to believe that the water front could not legally, and would not illegally and inequitably, be further extended. The doing so would be most prejudicial to their rights, while at the same time it would be a most serious injury to the general interests and privileges of the city.

Notwithstanding these and other objections, the obnoxious bill passed the House of Assembly by a majority of four, in which majority were two of the representatives from San Francisco. The other five representatives, who had voted against the measure, and some of whom had spoken often and forcibly upon its manifest injustice, now resigned their seats, and appealed to their constituents for an approval of their conduct, by standing as candidates for re-election. On the 14th of April, a new election took place. The course taken by the old representatives was chiefly opposed by a certain small section of the community, which was supposed to be personally interested in the passing of the bill complained of. On the 2d of January, in the preceding year, at one of the noted Peter Smith's sales, already mentioned, a great belt of land "covered with water," and extending six hundred feet beyond the existing and recognized water front, and embracing many thousand distinct lots, had been sold by the sheriff for something less than $7000, in order to satisfy a judgment against the city. The particular nature of the right of the city to this ground "covered with water," and the rights of the party holding the judgment, and of the sheriff to sell it, were matters imperfectly understood. Therefore the exact rights acquired by the purchasers nobody could distinctly estimate. As things stood, the buyers, who had speculated on a fortune of twice as many millions as they had paid thousands, could do nothing. But by enlisting the State on their side, and exciting the cupidity of the government, the Peter Smith jobbers might hope to derive incalculable benefits from their desperate bargains, by making a "compromise" with the commissioners proposed to be appointed under the contemplated bill. By the express terms of this bill, they would, most probably, have secured two-thirds of their purchases. To raise a fund for carrying on their scheme, and to interest parties personally in its success, certain of the new water lots were disposed of at low or nominal prices.

It was these original and subsequent buyers then, and their immediate friends and those whom they could in any way influence, that opposed the re-election of the representatives to the House of Assembly. The people generally felt that this matter was one of the utmost consequence to the welfare of the community. On the day of election many of the leading citizens closed their places of business, and devoted themselves to watching over the polls. The question at issue was one of principle, and not the mere personal choice of favorite candidates. The anti-extensionists, as they were called, were completely successful. Five votes to one of those polled were in favor of the old representatives; while, if it had been necessary, a still larger majority would have been obtained. At the close of the poll, the following parties were elected, viz.:—Samuel Flower, John Sime, John H. Saunders, James M. Taylor, and Elcan Heydenfelt.

Meanwhile, the bill had been carried into the Senate, and the parties for and against it seemed nearly balanced. Repeated public meetings were held at San Francisco on the subject, at which resolutions were passed strongly condemnatory of the bill and its known supporters. All classes of the community, except the reckless speculators who hoped to profit by the iniquitous Act, were bitterly opposed to the measure. If adopted, it would certainly have the effect of injuring the harbor and city to an incalculable, an irreparable extent; while, by throwing back the existing water front, and altering the grades of the streets, an immense deal of damage would be done upon private property. And all for what? Principally to enrich a few water-lot gamesters, and perhaps put a little money in the exhausted exchequer of the State. The pecuniary advantage of the transaction to the State was exceedingly doubtful at the best; while it was abundantly evident that interminable litigation and grievous loss to private parties and to the port itself were sure to arise. A large number of the members of the Legislature seem to have been at all times opposed to the prosperity of San Francisco; and would fain lay upon it what has often been considered,—by the citizens themselves, at all events,—more than a proportionate share of the burdens of the State. In the case in question, if even the government had the legal right to carry out the measure proposed by the obnoxious bill, which right was disputed by able and disinterested lawyers, the advantage to be derived by the State was very paltry in comparison with the vast amount of damage that would be occasioned to the city and individual citizens. This consideration plead for mercy from the spoiler, but it had little effect. The Senate, like the House of Assembly, seemed determined to kill the bird that laid the golden egg—for such were the taxes that San Francisco, in its prosperity, paid into the coffers of the State.

To show further the injustice and impropriety of the steps contemplated by the Extension Bill, we give an extract from a Report made by a portion of the committee appointed by the Senate on the subject:

"The harbor known in 1849 as the harbor of San Francisco, flanked north and south by the headlands of North and Rincon Points, and stretching inwards somewhat in the form of a crescent as far as Montgomery street, is now almost entirely filled up and occupied as the business part of the city. The boundary line of this, the eastern front, as fixed and declared permanent by the 4th section of an act of the Legislature, passed March 26th, 1851, extends even a little farther out into the bay than the headlands, and when the same shall be fully built up to and improved, the city will have a water front of sufficient extent and adequate depth of water to supply all the wants of her commerce and trade. The further extension of said front six hundred feet into the bay would not materially increase the extent on the eastern front, while a greater depth of water than the present front now enjoys, would not be necessary to enable vessels of the largest class to lie at the wharves.

"So far, therefore, as the eastern front of the city is concerned, we can discover no public necessity or conveniency which demands any action on the part of the Legislature, conflicting either in letter or spirit with the guarantee, or at least the declaration, that 'the said boundary line shall be and remain a permanent water front of said city,' contained in the act above referred to.

"The testimony taken by the committee conclusively shows that the shipping of the harbor would be materially injured by the further extension. Protection to the headlands, which is still to some extent enjoyed, would be destroyed, and the roadstead between the city and Goat Island, with a rapid current, and subject to strong south-easterly and north-westerly gales, would be materially contracted. This acknowledged injury, it has been suggested, can be counteracted by the erection of breakwaters off either or both North and Rincon Points. In a bay with such a variety of powerful currents, it would be difficult to predict the effect should such a plan be carried into execution. It might prove a greater injury to the water front than any yet inflicted upon it. But were the erection of breakwaters clearly demonstrated to be of great service, the practicability of accomplishing such a task by the State in so deep and turbulent a bay, by any expenditure within her means, is extremely doubtful. Any appropriation adequate even to the commencement of such a work, would, under Art. 8 of the Constitution, have to be submitted to the people for their approval.

"No necessity now exists for such a hazardous project, and it would be truly impolitic to create a necessity for it by making the proposed extension.

"But should the Legislature determine in any manner to extend the city front, we are decidedly of opinion that the necessity or use of erecting breakwaters would follow; and that if profit to the treasury should be a motive in making such extension, the connection of any breakwater scheme with it would entail upon the treasury losses infinitely greater than any imaginary or hoped-for profits could liquidate. The cost of breakwaters can only be reckoned by millions, and if the State embarks in the project with the hope that the proceeds of the sales of water lots will raise an adequate fund for that purpose, she will surely be disappointed.

"The right of the State to sell lots in the place indicated would be questioned perhaps by men most anxious for the sale to proceed; the title of the State could not escape being clouded in the minds of purchasers, when it is considered that a variety of interests adverse to the State would no doubt be in active operation. With these interests the public are familiar, and from one of them has proceeded the only proposition before the Legislature for an extension, and that proposition is based upon the assumption of a title adverse to and independent of the State, coupled with the proffer of a partnership interest of an entangling and intricate nature, as a consideration for the influence and authority of the State in carrying into effect a plan which your committee believe destructive to commerce, injurious to the property of a large class of citizens, and inconsistent in legislation.

"Respectful and temperate language cannot be employed in giving complete expression to the sentiments entertained of this proposition, and therefore your committee refrain from further allusion to it."

The Report, from which the above extract is taken, then discusses at length the nature of the various rights claimable by Congress, by the State, and by the city, to the land "covered with water," in question; and concludes thus: "Even if the water front right, being a vested right, could be successfully questioned, bad faith to the citizens of San Francisco would be truly chargeable against the government, were an act passed by which said water front privileges and advantages would be destroyed."

The united people of San Francisco, excepting always the small clique of speculators already mentioned, considered that all law, justice, and expediency, were opposed to the projected extension; the supporters of the bill in the Legislature could only talk of the absolute and wilful right of the State to do what it chose with its own pretended property, without regard to those who might be ruined by its so doing. After several debates, the bill came to a final vote in the Senate upon the 26th of April, when thirteen members voted for, and the like number against it. Happily, the president of the chamber, Lieutenant-Governor Purdy, who in cases of parity possesses a casting vote, gave his against the bill. Thus, by the narrowest chance, San Francisco escaped this severe stroke. Perhaps the Peter Smith speculators in extension water lots may at some future time renew their attempt to carry out their views, and may persuade even a majority of the Legislature—at all times jealous of the greatness and independence of San Francisco—to further their iniquitous schemes. The citizens, therefore, will require to be ever watchful on this subject, until a constitutional and legal declaration be obtained, and which will be beyond all cavil or question, that the existing boundary line shall be really and truly the permanent water front of the city.

APRIL

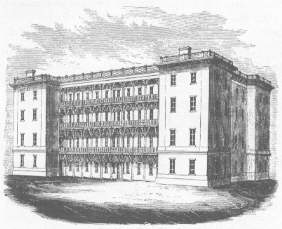

7th.—The corner-stone laid of the United States Marine Hospital, when the

usual interesting ceremonies observed on similar occasions, were performed.

On the 10th of December, 1852, the mayor approved of an ordinance, which

the common council had passed, by which he was directed to convey to the

Government of the United States six fifty-vara lots, situated at Rincon

Point. These were intended for the site of the magnificent structure, the

corner-stone of which was laid to-day. The building was erected in the

course of this year (completed December 12th), and is now a striking ornament

to the city. It is built of brick, and is four stories high. It is 182

feet long by 96 feet wide. At one time five hundred patients can be comfortably

lodged, while, in cases of necessity, so many as seven hundred can be accommodated.

The total cost has been about a quarter of a million of dollars. This hospital

has been built and will be supported by the United States, from the fees

paid into the treasury by the sailors of every American vessel entering

our ports. The sum of twenty cents a month is deducted from their wages,

and paid by the master of every vessel to the custom-house. In return,

every sick and disabled seaman reaching San Francisco is entitled to a

certificate from the collector for admission to the hospital. As sailors

under foreign flags pay no fees, they are of course not entitled to the

privileges of the institution. This hospital and the State Marine Hospital

sufficiently provide at present for the wants of the sick in San Francisco.

There are several other hospitals of a semi-public or private nature, which

take care of such sick persons as may not be entitled to admission into

either of the two mentioned, or who may prefer the accommodations of less

public institutions.

APRIL

7th.—The corner-stone laid of the United States Marine Hospital, when the

usual interesting ceremonies observed on similar occasions, were performed.

On the 10th of December, 1852, the mayor approved of an ordinance, which

the common council had passed, by which he was directed to convey to the

Government of the United States six fifty-vara lots, situated at Rincon

Point. These were intended for the site of the magnificent structure, the

corner-stone of which was laid to-day. The building was erected in the

course of this year (completed December 12th), and is now a striking ornament

to the city. It is built of brick, and is four stories high. It is 182

feet long by 96 feet wide. At one time five hundred patients can be comfortably

lodged, while, in cases of necessity, so many as seven hundred can be accommodated.

The total cost has been about a quarter of a million of dollars. This hospital

has been built and will be supported by the United States, from the fees

paid into the treasury by the sailors of every American vessel entering

our ports. The sum of twenty cents a month is deducted from their wages,

and paid by the master of every vessel to the custom-house. In return,

every sick and disabled seaman reaching San Francisco is entitled to a

certificate from the collector for admission to the hospital. As sailors

under foreign flags pay no fees, they are of course not entitled to the

privileges of the institution. This hospital and the State Marine Hospital

sufficiently provide at present for the wants of the sick in San Francisco.

There are several other hospitals of a semi-public or private nature, which

take care of such sick persons as may not be entitled to admission into

either of the two mentioned, or who may prefer the accommodations of less

public institutions.

APRIL 11th.—The Jenny Lind steamer, when on her passage from Alviso to San Francisco, with about one hundred and twenty-five passengers on board, met with a dreadful accident. At half-past twelve o'clock, when nearly opposite the Pulgas Ranch, and when the company on board were about sitting down to dinner in the after cabin, a portion of the connecting steam-pipe was blown asunder, and instantly the destructive vapor burst open the bulkhead of the cabin, and swept into the crowded apartment. Many were dangerously scalded, and a large number instantly struck dead, by inhaling the intensely heated atmosphere. Thirty-one persons were either killed on the spot, or soon afterwards died, from the effects of injuries received from the explosion. This catastrophe occurring immediately after the losses of so many fine steamships at sea, already noticed, excited much sorrowful interest in the city.