The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1853.

OCTOBER 13th.—The most important decision ever given by the Supreme Court of California was pronounced to-day in the case of Cohas vs. Rosin and Legris. Previous decisions both of this and the lower legal tribunals had established principles which unsettled the city titles to nearly every lot of ground within the municipal boundaries, and mightily encouraged squatterism. By these decisions, one title had just seemed as good or as bad as another; possession being better than any. The alarming consequences of these doctrines forced both bench and bar into further inquiries and minute researches into the laws, usages and customs of Spanish or Mexican provinces and towns. The new information thus acquired was brought to bear upon the suit above named, where principles were evolved and a precedent formed of the utmost consequence to the community, and which have nearly settled, though not quite, the “squatter” questions. The decision was pronounced by Judge Heydenfeldt, and was concurred in by Chief Justice Murray (although upon somewhat different grounds) and Judge Wells. Without entering upon the merits of the particular case in question we give the “conclusions” come to:

“Firstly, That by the laws of Mexico, towns were invested with the ownership of lands.

“Secondly, That by the law, usage and custom in Mexico, alcaldes were the heads of the Ayuntamientos, or Town Councils, were the executive officers of the towns, and rightfully exercised the power of granting lots within the towns, which were the property of the towns.

“Thirdly, That before the military occupation of California by the army of the United States, San Francisco was a Mexican pueblo, or municipal corporation, and entitled to the lands within her boundaries.

“Fourthly, That a grant of a lot in San Francisco, made by an alcalde, whether a Mexican or of any other nation, raises the presumption that the alcalde was a properly qualified officer, that he had authority to make the grant, and that the land was within the boundaries of the pueblo.”

These conclusions sustain all alcaldes’ grants in the city, no matter though the alcalde himself had been illegally appointed and had made a dishonest use of his power. By this decision—all opposing precedents having been expressly set aside by the court—many notoriously fraudulent alcalde grants have been legalized; but that seems a small price to pay for the full assurance of title now given to the proprietors of the most valuable part of the ground within the municipal bounds.

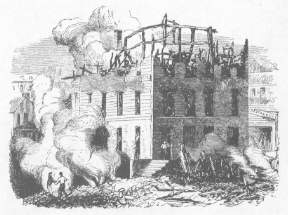

OCTOBER

22d.—Destruction by fire of the St. Francis Hotel, at the corner of Dupont

and Clay streets. This was a famous house in the history of San Francisco.

It was built in the fall of 1849, and in the basement story the polls were

held of the first State election. It was afterwards converted into a first-class

hotel. The structure was composed of the slightest and most inflammable

materials; and it had long been matter of surprise that it had escaped

the many conflagrations which had so repeatedly destroyed great portions

of the city. When, at last, it was consumed, people were not only no whit

surprised, but many were absolutely glad that it was so, since the danger

of its long anticipated burning spreading to the neighboring tenements

was thereby put an end to. The strenuous exertions of the firemen confined

the fire to the building in which it originated. The damage was estimated

at $17,000. One lodger was burned to death; and several firemen were very

severely injured by the flames. The masterly efforts of the Fire Department

on this occasion were much praised.

OCTOBER

22d.—Destruction by fire of the St. Francis Hotel, at the corner of Dupont

and Clay streets. This was a famous house in the history of San Francisco.

It was built in the fall of 1849, and in the basement story the polls were

held of the first State election. It was afterwards converted into a first-class

hotel. The structure was composed of the slightest and most inflammable

materials; and it had long been matter of surprise that it had escaped

the many conflagrations which had so repeatedly destroyed great portions

of the city. When, at last, it was consumed, people were not only no whit

surprised, but many were absolutely glad that it was so, since the danger

of its long anticipated burning spreading to the neighboring tenements

was thereby put an end to. The strenuous exertions of the firemen confined

the fire to the building in which it originated. The damage was estimated

at $17,000. One lodger was burned to death; and several firemen were very

severely injured by the flames. The masterly efforts of the Fire Department

on this occasion were much praised.

OCTOBER 24th.—First telegraphic communication between San Francisco and Marysville. This was the completion of the line of the State Telegraph Company, already noticed. The whole length of the wire is two hundred and six miles; and it was erected in seventy-five days. The rates charged were, and are now as follows: From San Francisco to Stockton, Sacramento or Marysville, two dollars for the first ten words; and for each additional five words, seventy-five cents. From San Francisco to San José, for the first ten words, one dollar, and for each additional five words forty cents.

NOVEMBER.—The “Lone Mountain Cemetery” projected. A tract of land three hundred and twenty acres in extent, lying between the presidio and the mission, is to be laid out in a proper manner as a new resting-place for the dead, the cemetery of Yerba Buena being considered, by the planners of the new grounds, too near the city for a permanent burial-place. The new cemetery is located near the well-known “Lone Mountain,” situated three or four miles west of the plaza. From the summit of this beautifully shaped hill may be obtained one of the finest and most extensive views of land and water. At the date of writing, very material and expensive improvements are being made upon the grounds, to adapt them for the purposes of a cemetery.

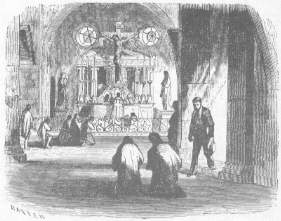

NOVEMBER

9th.—The day of St. Francis, the anniversary of the foundation of the Mission

Dolores, in 1776. In the preceding pages, occasional allusions have been

made to the former grandeur and subsequent decline of this mission. At

present, the chief thing worthy of notice about the place is the old church.

This is constructed of adobes, and is a spacious building. The exterior

is partially whitewashed and is very plain in appearance, although the

front pretends to some old-fashioned architectural decorations, and shows

several handsome bells. The capacious interior is dark, cold and comfortless.

The walls and roof are roughly painted, and upon the former are several

common paintings of saints and sacred subjects. The ornaments upon and

around the great altar are of the tinsel character usually adopted in ordinary

Roman Catholic churches. It is presumed they are of no great pecuniary

value. Public worship is still regularly celebrated in this huge and gloomy

temple. The usual audiences are a few women, whose features and dress proclaim

their Spanish orlgin. If any of the fast-thinking, doing and living people

of San Francisco could be induced to “pause and moralize a while,” there

is no spot so fitted to encourage the unwonted mood, as the dismal, silent

and deserted interior of the Mission Church. There is an awe and apparent

holiness about the place which the casual heretical visitor cares not to

disturb, as he perhaps humbly kneels on the damp, earthen floor, and worships

in secret his own God. A walk round the small graveyard attached to the

church will only deepen his meditation as he gazes on the tombs of departed

pioneers and gold-hunters, and reflects upon the glory of the ancient patriarchal

times of tame Indians and their ghostly keepers.

NOVEMBER

9th.—The day of St. Francis, the anniversary of the foundation of the Mission

Dolores, in 1776. In the preceding pages, occasional allusions have been

made to the former grandeur and subsequent decline of this mission. At

present, the chief thing worthy of notice about the place is the old church.

This is constructed of adobes, and is a spacious building. The exterior

is partially whitewashed and is very plain in appearance, although the

front pretends to some old-fashioned architectural decorations, and shows

several handsome bells. The capacious interior is dark, cold and comfortless.

The walls and roof are roughly painted, and upon the former are several

common paintings of saints and sacred subjects. The ornaments upon and

around the great altar are of the tinsel character usually adopted in ordinary

Roman Catholic churches. It is presumed they are of no great pecuniary

value. Public worship is still regularly celebrated in this huge and gloomy

temple. The usual audiences are a few women, whose features and dress proclaim

their Spanish orlgin. If any of the fast-thinking, doing and living people

of San Francisco could be induced to “pause and moralize a while,” there

is no spot so fitted to encourage the unwonted mood, as the dismal, silent

and deserted interior of the Mission Church. There is an awe and apparent

holiness about the place which the casual heretical visitor cares not to

disturb, as he perhaps humbly kneels on the damp, earthen floor, and worships

in secret his own God. A walk round the small graveyard attached to the

church will only deepen his meditation as he gazes on the tombs of departed

pioneers and gold-hunters, and reflects upon the glory of the ancient patriarchal

times of tame Indians and their ghostly keepers.

The mission has always been a favorite place of amusement to the citizens of San Francisco. Here, in the early days of the city, exhibitions of bull and bear fights frequently took place, which attracted great crowds; and here, also, were numerous duels fought, which drew nearly as many idlers to view them. At present, there are two race-courses in the neighborhood, and a large number of drinking-houses. Two plank-roads lead thither from the city, upon both of which omniblises run every half hour. The mission lies within the municipal bounds, and probably will soon be united with the city by a connected line of buildings. The highway to San José and the farther south, runs through the village, while around it are fine green hills and fertile fields, and hotels and places of public recreation. These things all make the old home of the “fathers” a place of considerable importance to our health and pleasure seekers. On fine days, especially on Sundays, the roads to the mission show a continual succession, passing to and fro, of all manner of equestrians and pedestrians, and elegant open carriages filled with ladies and holiday folk.

Since we have given elsewhere short separate notices of some of the leading races, not American, that people San Francisco, we may here say a few words upon that one which first settled in the country—the Spanish. Over the whole of California, there may be probably about 20,000 persons of Spanish extraction; and in San Francisco alone, some 3,000. It is of the last only that we would speak. Few of them are native Californians. Perhaps one-half of the number are Mexicans, and one-third Chilians. The remaining sixth consists of Peruvians and natives of Old Spain, and of parts of Spanish America other than Mexico, Chili and Peru. The Hispano-Americans, as a class, rank far beneath the French and Germans. They are ignorant and lazy, and are consequently poor. A few of their number may have a high social standing in the city, while some more bear a respectable position. For these there is one page of a French tri-weekly newspaper written in the Spanish language. It is not of them, nor of the few native Californians, who are gentlemen by nature, that we speak, but of the great mass of the race. Many of the Chilians are able both to read and write; few of the Mexicans can. Both peoples, when roused by jealousy or revenge, as they often are, will readily commit the most horrid crimes. In proportion to their numbers, they show more criminals in the courts of law than any other class. The Mexicans seem the most inferior of the race. They have had no great reason to love the American character, and, when safe opportunity offers, are not slow to show detestation of their conquerors. The sullen, spiteful look of the common Mexicans in California is very observable. The Chilians in the time of the “ Hounds” were an oppressed and despised people. Since that period the class has perhaps improved. The Hispano-Americans fill many low and servile employments, and in general engage only in such occupations as do not very severely tax either mind or body. They show no ambition to rise beyond the station where destiny, dirt, ignoratice and sloth have placed them. They seem to have no wish to become naturalized citizens of the Union, and are morally incapable of comprehending the spirit and tendencies of our institutions. The most inferior class of all, the proper “greaser,” is on a par with the common Chinese and the African; while many negroes far excel the first-named in all moral, intellectual and physical respects.

The Hispano-Americans dwell chiefly about Dupont, Kearny and Pacific streets—long the blackguard quarters of the city. In these streets, and generally in the northern parts of the city, are many dens of gross vice, which are patronized largely by Mexicans and Chilians. Their dance, drink and gambling houses are also the haunts of negroes and the vilest order of white men. In the quarrels which are constantly arising in such places many treacherous, thieving and murderous deeds are committed. A large proportion of the common Mexican and Chilian women are still what they were in the days of the “Hounds,” abandoned to lewd practices, and shameless.

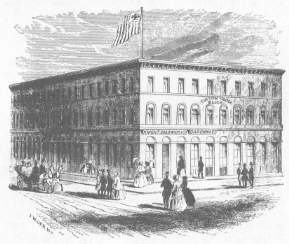

The

large and elegant building called “Custom-House Block,” at the south-east

corner of Sansome and Sacramento streets, was completed and partially occupied

during this month. It was constructed at a cost, exclusive of the land,

of $140,000; and is a substantial structure, three stories high, besides

a basement, fronting eighty feet on Sansome and one hundred and eighty-five

feet on Sacramento street. The various offices connected with the custom-house

and naval department, besides a billiard room, and sundry other offices

and stores, are in the second and third stories.

The

large and elegant building called “Custom-House Block,” at the south-east

corner of Sansome and Sacramento streets, was completed and partially occupied

during this month. It was constructed at a cost, exclusive of the land,

of $140,000; and is a substantial structure, three stories high, besides

a basement, fronting eighty feet on Sansome and one hundred and eighty-five

feet on Sacramento street. The various offices connected with the custom-house

and naval department, besides a billiard room, and sundry other offices

and stores, are in the second and third stories.

DECEMBER 2d.—The mail steamship Winfield Scott, on her way from San Francisco to Panama, was wrecked on the rocky and desolate Island of Anacapa, near the Island of Santa Cruz, off Santa Barbara. The passengers and most of the mail bags were saved, but the ship was a total loss. The accident was caused by dense fogs and ignorance of the exact position of the ship.

DECEMBER 5th.—Annual election of the Fire Department, when the following officers were chosen: Chief Engineer.—Charles P. Duane. Assistant Engineers.—E. A. Ebbetts, Joseph Caprise and Charles F. Simpson.

DECEMBER 13th.—The Barque Anita sailed with about two hundred and forty volunteers to join a small band of adventurers that had lately left San Francisco on a filibustering expedition against Lower California and Sonora. The circumstances attending this expedition show in a remarkable manner the wild and restless spirit that influences so many of the people of California. Not content with their own large territory, much of which is still unexplored, and nearly all of which that is known is characterized by extraordinary richness in minerals, fertility of soil, beauty of scenery, and mildness and salubrity of climate—by everything, in short, that could tempt an energetic immigrant to develope its unusual advantages—many of our restless people sighed for new countries, if not like Alexander for new worlds, to see and conquer. The Mexican province of Sonora had long been reputed to be among the richest mineral regions in the world. Its mines, however, had never been properly developed. The Mexican character is not a very enterprising one. At the same time, the ravages of the numerous tribes of warlike Indians that inhabit many parts of Sonora and its frontier, had farther checked all efforts to work the known gold and silver mines there. The country otherwise was a fine agricultural and pastoral one; and, if slaves could only be introduced to cultivate and reap the teeming fields, the owners would draw immense revenues from them. To conquer, or steal this rich country, was therefore a very desirable thing. That it belonged in sovereignty to a friendly and peaceable power, and that some seventy thousand white people inhabited and possessed the land, appeared matters of no great consequence. The government of Mexico was a worthless one, surely, and the citizens of Sonora were, or should be, dissatisfied with it, and had a right to rebel, and call upon foreigners to aid them in their rebellion. If they did not, why, their culpable negligence was certainly no fault of the filibusters. The Sonorians ought to rise, proclaim their independence, and cry for help from all and sundry. That was enough. The filibusters needed no particular invitation. They were determined to succor the poor Sonorians, and themselves; and so they gathered together with arms and ammunition for the purpose. Walker was another Lopez; Sonora, another Cuba.

About a twelvemonth before this date the grand scheme was first projected, and during the following summer was matured. Scrip was largely printed and circulated at fair prices among speculative jobbers. This paper was to be redeemed by the first proceeds of the new government. The nominal and perhaps real leader of the movement was a gentleman, William Walker to wit, who has already figured in these pages, as the champion of the press and popular rights against the alleged corrupt judiciary of former times. Walker is said to be personally a brave, highly educated and able man, whatever may be thought of his discretion and true motives of conduct in the expedition. He seems to have taken a high moral and political position in the affair, though his professions were peculiar and their propriety not readily admitted by downright sticklers for equity and natural justice. A few of his coadjutors were perhaps also men of a keen sense of honor, who forgot, or heeded not, in the excitement of the adventure, the opinions of mere honest men upon the subject. But the vast majority of Walker’s followers can only be viewed as desperate actors in a true filibustering or robbing speculation. The good of the wretched and Apache-oppressed Sonorians was not in their thoughts. If they succeeded, they might lay the sure foundations of fortunes; if they failed, it was only time and perhaps life lost. In either event, there was a grand excitement in the game.

What Americans generally are to other nations, so are the mixed people of California to Eastern Americans themselves. All the impulsive characteristics of the natives of the Atlantic States are on the Pacific carried out to excess. Americans, and particularly those in California, are not altogether devoted to money; they oftentimes love change and excitement better. The golden gains to be sometimes won here by strange speculations early engendered a most restless disposition in society. The adventurous character of the succeeding immigrants readily received the impress and spirit of the place. What, our people seem to think, is the worth of life, wanting emotion, wanting action? At whatever hazard, most persons here must have occasional excitement—new speculations, leading to personal adventure, change of scene and variety of life. Danger to life and limb and loss of property will not stand in the way. They will overlook the fairest prospect close at band, with its dull routine of duty and labor, to seek for an inferior one at a distance. They are almost invariably dissatisfied with their present condition, whatever that may be. The world moves not fast enough for their boundless desires. Thus a new land, where hope and fancy see all things, is to them a charmed land. They will seek and know its qualities, or perish in the attempt. Discontent and restlessness make the true spirit of “progress” that is ever unsatisfied with the dull present, the practical and real. These are the characteristics of all great men and great races, and are the strongest signs of their superior intellect.

The spirit of progress is probably a most unhappy one to individuals, although it tends to raise a nation to the height of wealth and glory. Knowledge is power, the attribute of a god; yet as the satirist says, increase of knowledge is only increase of sorrow. Knowledge—power—” progress,” is the Anglo Saxon disposition, which has been developed on a large scale in the American character. Brother Jonathan, like the Israelite of old, seems doomed everlastingly to wander over the earth. His journey fairly began nearly a century since. On, on he must go. Excelsior! is his cry. The morality of the various steps in the fated pilgrimage—as morals, social and political, are commonly understood among old-fashioned people—may be dubious; yet the weary work must proceed. It is the fate of America ever to “go ahead.” She is like the rod of Aaron that became a serpent and swallowed up the other rods. So will America conquer or annex all lands. That is her “manifest destiny.” Only give her time for the process. To swallow up every few years a province as large as most European kingdoms is her present rate of progress. Sometimes she purchases the mighty morsel, sometimes she forms it out of waste territory by the natural increase of her own people, sometimes she “annexes,” and sometimes she conquers it. Her “progress” is still steadily onward. Pioneers clear the way. These are political agents with money bags, or settlers in neglected parts of the continent, or peaceable American citizens who happen to reside in the desired countries, and who wish to dwell under the old “Stars and Stripes,” or they may be only proper filibusters, who steal and fight gratuitously for their own fast-following Uncle Sam. When they fall in their schemes, they are certainly scoundrels, and are commonly so termed; when they succeed, though they be dubbed heroes, they are still the old rogues. Meanwhile AMERICA (that is the true title of our country) secures the spoils won to her hand, however dishonestly they may have come. That is only her destiny, and perhaps she is not so blamable as a nation in bearing it willingly. One may profit by the treason, yet hate the traitor. Let the distant monarchs of the lands beyond the great lakes and the tawny people of the far south look to it. America must round her territories by the sea. Like Russia, she is steadily creeping over the world, but different from that empire, her presence bestows freedom and good upon the invaded nations, and not despotism, ignorance, and unmanly, brutal desires.

The pioneers into Sonora were Walker and his people. They never reached their destination. Lower California was in the way, and they thought it best to begin on the small scale, and secure it first. On the 30th of September of this year, the brig Arrow, which was about to be employed to convey the filibusters to the land of promise, was seized by order of General Hitchcock, commanding the United States forces on the Pacific, and acting under orders or a sense of his duty to protect a neighboring friendly power from being wrongfully attacked by Americans. This measure involved General Hitchcock in unpleasant litigation, and seems to have disgusted him with attempting to interfere farther in the filibusters’ movements. For want of sufficient legal evidence to show the destination of the Arrow and the character of the preparations making by those connected with the affair, or rather, perhaps, through disinclination of the prosecutors to go on with the proceedings, the case was abandoned and the vessel released. Meanwhile, the other officials here of the United States Government, whose duty it was to prevent all piratical and filibustering expeditions from leaving the port, gave little attention to the subject, and appeared wilfully to neglect their most urgent duties. As for the State and city authorities, it seemed to be considered none of their business to move in the matter. The newspaper press was neutral, or at all events did not (with one or two exceptions) loudly condemn the course intended to be pursued by the known filibusters. Encouraged by these circumstances, the adventurers soon procured another vessel, the barque Caroline, and shortly afterwards (16th October), forty-six of their number sailed in her from San Francisco for the lower coast. Early in November, they reached the town of La Paz, situated within the Gulf of California, and in the southern division of the peninsula. There they landed, scattered the surprised inhabitants, secured the governor, proclaimed the independence of Lower California, declared the civil code of Louisiana the law of the land, hauled down the Mexican flag and hoisted their own—all within half an hour. A slight engagement afterwards took place between the Mexicans and the invaders, in which the latter were successful, after killing a few of the enemy. This was the battle of La Paz. Mr. Walker then was nominated “President of the Republic of Lower California,” and chose, or had chosen for him his various Secretaries of State, War and Navy, and other grand functionaries of the new government. As there were fewer than fifty men to select from, a pretty fair proportion of the party became suddenly dignitaries in the Republic. The President, his staff and whole forces soon forsook La Paz, the particular reason for attacking which town at this juncture of events is not plain, though perhaps it was only to create a “sensation.” There was not even the pretence made that the inhabitants of the place, or any of the natives of Lower California, had invited the presence of the spoilers of their property. Walker and his party now retreated altogether from the gulf; and carrying with them the archives of the government, sailed for Ensenada, a place about a hundred miles below San Diego, on the Pacific side of the peninsula. Here, in a thinly peopled and unattractive country, and at a long distance from any Mexican troops, they were safe for a time; and here they established their “Head Quarters,” until reinforcements should reach them from San Francisco. It was understood that the seizure of Lower California was only the first step in the proposed conquest of Sonora, which was all along the grand object of the expedition.

When news of this short campaign reached San Francisco, there was a mighty ado with the friends and sympathizers of the expedition. Among the few initiated in the supposed secret causes of the adventure, there were brilliant hopes of the indefinite extension of one of the peculiar “domestic institutions” of the South, and among all were glorious dreams of conquest and plunder. The national flag of the new Republic was run up at the corner of Kearny and Sacramento streets, and an office was opened for the purpose of enlisting recruits. The excitement was great in the city. At the corners of the streets and in barrooms, groups of intending buccaneers and their friends collected, and discussed the position of affairs. More volunteers appeared than there were means of conveying to the scene of action. News next reached the city of the battle of La Grulla, near Santo Tomas, where the filibusters, when said to be in the act of helping themselves to the cattle and provisions of the natives, were severely handled, and a few of them slain. This, however, only fired the recruits the more to help their oppressed brethren. Why could not the Lower Californians, poor, ignorant brutes, have been contented with the beautiful scrip of the new Republic for their paltry provisions? The rage for war—freedom to the Mexicans, death to the Apaches, and plunder to the Americans—spread over all California, and numbers hastened from the mining regions to San Francisco, to depart southward in time and share in the spoil of the conquered land. The authorities meanwhile, looked calmly on, and took no steps to prevent the departure of the filibusters. The newspapers recorded their various movements at length, and in general either indirectly praised, or did not strongly condemn them. People in private circles laughed, and talked over the business coolly. They generally thought, and said, it was all right—at all events, it was a fine specimen of the go-aheadism of Young America. Moneyed men even advanced considerable sums for the use of the expeditionists, and the scrip of the new Republic was almost saleable on ‘Change, at a dime for a dollar.

We have mentioned this affair at some length, more to show the general wild and reckless character of the people, and the state of public opinion upon filibustering, in San Francisco, and in California at large, than to chronicle the particular doings of the adventurers. Our people are mostly in the prime of life, their passions are of the strongest, they have an acute intellect, absolute will and physical strength, but they are not distinguished by high moral and political principle. They are sanguine in whatever things they undertake, and are more inclined to desperate deeds, than to the peaceful business of ordinary life. Had Walker’s party succeeded in reaching Sonora and been able to stand their own for a time or perhaps signally to defeat the Mexicans in a pitched battle, ten thousand of our mixed Californians would have hastened to their triple-striped two-star standard. Against such a force not all the power of Mexico would have been sufficient to dislodge the invaders from Sonora. Other tens of thousands would have flocked into the country, and perforce it would have been thoroughly Americanized. Undoubtedly this will happen some day. Is it not “manifest destiny?” People here certainly look upon it as such, and hence very little fault has been found, in general, with the proceedings of the filibusters. The principles of action now existing in California, in so far at least as regards neighboring countries, are something like those of Wordsworth’s hero, who acted upon

“The good old rule, the simple plan—

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.”

Rob Roy was a great man in his day; and in our own times the Californians are the greatest of a great people. That is a fact.

To finish the story of Walker’s exploits. The Anita safely bore her contingent to “Head Quarters” at Ensenada, and by other opportunities a considerable number of volunteers went thither. They were generally well armed with revolvers, rifles and knives. On their departure, the recorder’s court at San Francisco had much less daily business, and the city was happily purged of many of the old squad of rowdies and loafers. Strengthened by such an accession to his forces, opposed to which no body of Mexicans in that part of Lower California could appear in the field, Walker now, with a stroke of his pen, for he is said to be even abler as a writer than as a warrior, abolished the Republic of “Lower California,” and proclaimed in its stead that of “Sonora,” which comprised the province of that name and the peninsula itself. Most of the great prizes in the lottery had already been distributed. However, Col. H. P. Watkins, of the Anita contingent, had the honor of being appointed the “Vice-President.” This gentleman and some of his fellow-dignitaries subsequently underwent a trial at San Francisco for their filibustering practices, the result of which will be noticed under the proper date. In Lower California, various “decrees,” proclamations and addresses to the natives and to his own soldiers were made by the “President.” They dwelt upon the “holiness” of the invaders’ cause, and were very grandiloquent. The march was being formed for Sonora, straight.

Meanwhile, dissensions were breaking out among the men. The rank and file, the tag, and bobtail of the expedition, had considerable difficulty in digesting the stolen or scrip-bought beef, always beef, and Indian corn, always corn, that formed their rations. They fancied that their officers “fared sumptuously every day,” which very likely was not the case. Any thing will serve as an excuse for behavior that has been predetermined. So these epicures and haters of beef and corn, to the number of fifty or sixty, gave up, without a sigh, Walker, Sonora and their frugal meals. Other desertions subsequently took place, and the staunch filibusters were gradually reduced to a very few. To improve the moral tone of his army, Walker caused two of his people to be shot and other two to be flogged and expelled, partly for pilfering and partly for desertion. The San Franciscan journals had now little mercy on the expedition and all connected with it. It was a farce, they said; and its end was just what they had expected. For a while there remained a remnant of the filibusters loafing about Ensenada, or Santo Tomas—or God knows where—looking, like the immortal Micawber, for “something to turn up.” Subsequently, however, as will hereafter be seen, they surrendered themselves as prisoners to the United States authorities.

DECEMBER 24th.—Opening of the “Metropolitan Theatre.” Theatricals, and especially that class of them in which music bears a considerable share, have always been largely patronized by the San Franciscans. It was thought proper to have a more magnificent temple for dramatic and operatic entertainments than any hitherto erected in the city, and the “Metropolitan” accordingly was built and opened. This is one of the finest theatres in America, and is distinguished by the beautiful and chaste appearance of the interior. The house is built of brick. The management of the theatre was under the care of Mrs. Catherine N. Sinclair. She opened the splendid structure with an excellent stock company, among whom there immediately began to appear “stars” of the first magnitude, which have since continued in rapid succession. The prices of admission were—for the orchestra and private boxes, $3, for the dress circle and parquette, $2, and for the second and third circles, $1. The School for Scandal, in which Mr. James E. Murdock played the part of “Charles Surface,” and Mrs. Sinclair, the manageress, that of “Lady Teazle,” and the farce of Little Toddlekins, were the performances of the evening.

DECEMBER 26th.—Great sale of one hundred and twenty water lots belonging to the city, when the gross sum realized was $1,193,550. These lots formed in all four small sized blocks of land, covered with water, lying upon each side of Commercial street wharf. They extended between Sacramento and Clay streets, and from Davis street eastward two blocks. Most of the lots measured twenty-five feet in front to a street, and fifty-nine feet nine inches in depth. These brought on an average between $8,000 and $9,000 a lot. The corner lots, which faced two streets, brought from $15,000 to $16,000. A few larger lots brought from $20,000 to $27,000. There was an average depth of about eight feet of water, at low tide, upon these blocks of land; and to make them fit to receive buildings would require the expenditure of large sums of money. The enormous prices obtained for such small lots of ground, “covered with water,” show the confidence which capitalists had in the future prosperity of the city. The sale was only for ninety-nine years, after March, 1851, being the period for which the State had conveyed the property to the city. In terms of the original grant, the city was obliged to pay over to the State twenty-five per cent. of the proceeds of the sale. The sum of $185,000 was likewise appropriated to satisfy any claims which several of the wharf companies adjoining the lots disposed of had pretended to the slips, now sold. After these deductions were made, a very handsome sum was left to replenish the municipal exchequer, and relieve it from many pressing obligations which had been gradually accumulating.

DECEMBER

28th.—Great sale of the State’s interest in water property, when lots to

the value of $350,000 were sold. This property was situated between Broadway

and Pacific streets. It was partly covered with water, and partly dry land,

although covered with water in 1849, and is a portion of the property called

the “Government Reserve” on the ordinary maps of the city.

DECEMBER

28th.—Great sale of the State’s interest in water property, when lots to

the value of $350,000 were sold. This property was situated between Broadway

and Pacific streets. It was partly covered with water, and partly dry land,

although covered with water in 1849, and is a portion of the property called

the “Government Reserve” on the ordinary maps of the city.

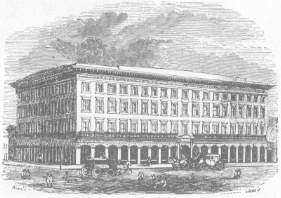

The magnificent structure known as “Montgomery Block” was completed toward the close of this year. This is the largest, most elegant, and imposing edifice in California, and would attract especial attention in any city, though it occupies a site that was partially covered by the waters of the bay as late as 1849. It has a front of 122 feet on the west side of Montgomery street, from Washington to Merchant street, along which streets it extends 138 feet, presenting an unbroken façade on these three streets of nearly 400 feet. It is owned by the law firm of Halleck, Peachy, Billings & Parke.