The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1853.

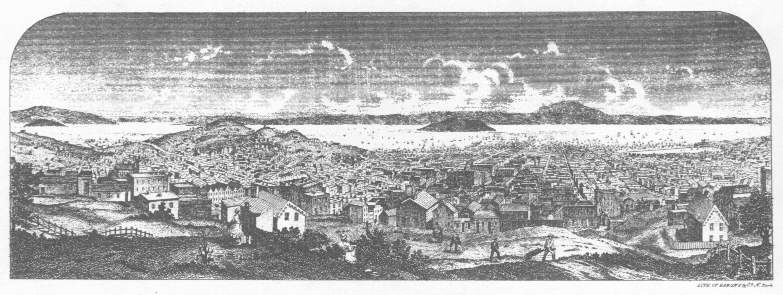

MANY of the observations regarding San Francisco and its citizens made in the reviews of the several years since 1849, and in the chronological order of the proper “Annals,” may be fitly applied in describing the place and people at the present time. Cities change neither their moral nor physical nature in a twelvemonth. The same broad characteristics that marked the first great increase in the number of inhabitants are still visible. At the beginning of 1854, the citizens are as remarkable, as in 1849 they were, for energy for good and evil, and the power of overcoming physical obstacles, and creating mighty material changes. Every where in the city is the workman busy at his trade. Laborers of various kinds are still hewing down the rocky hills, excavating the streets, grading and planking them; they are levelling building lots, and rearing mammoth hotels, hospitals, stores, and other edifices; they are piling and capping water lots, and raising a new town upon the deep; gas and water works are forming; sand hills are being continually shifted, and cast, piecemeal, into the bay. The wharves are constantly lined with clipper and other ships, the discharge of whose cargoes gives employment to an army of sailors and boatmen, stevedores and ‘longshoremen. The streets are crowded with wagons and vehicles of every description, bearing goods to and from the huge stores and warehouses. The merchant and his clerk are busily buying and selling, bartering and delivering; and fleets of steamers in the bay and rivers are conveying the greater part of the goods disposed of to the interior towns and mining districts. The ocean is covered with a multitude of ships that hear all manner of luxuries and necessaries to San Francisco. Seven hundred and forty-five thousand tons of the most valuable goods were brought into port in one year. All the inhabitants of the city are in some measure engaged in commerce, or in those manufactures and trades that directly enable it to be profitably carried on, or in supplying the wants, the necessities and extravagances of the proper commercial community. The gold of the mines pays for every thing, and it all passes through San Francisco. Elsewhere we have talked of the high ordinary prices of labor, and the assurance of employment to the earnest workman, who is not above turning his hand to any kind of work, however severe and irksome it may be.

Numerous fortunes were rapidly made in the early days of San Francisco, when the golden gains were shared among a few long-headed speculators, who fattened on the public means, or who took advantage of peculiar circumstances, or who had fortune absolutely thrust upon them by lucky accident. The ordinary rates of profit in all kinds of business were very great, and unless the recipients squandered their gains in gambling, debauchery, and extravagance, they were certain in a very short time to grow rich. Capital, when lent, gave at all times a return of from thirty to sixty per cent. per annum, with the best real security that the country and the times could afford. In two years’ space, the financier doubled his capital, without risk or trouble to himself; and the accumulation went on in geometrical progression. But chiefly it was the holders of real estate that made the greatest fortunes. The possession of a small piece of building ground in or about the centre of business was a fortune in itself. Those lucky people who held lots from the times before the discovery of gold, or who shortly afterwards managed to secure them, were suddenly enriched, beyond their first most sanguine hopes. The enormous rents paid for the use of ground and temporary buildings in 1849 made all men covetous of real estate. By far the greater part had originally belonged to the city, formerly the so-called pueblo, or village of Yerba Buena; but the guardians of its interests, from the conquest downwards, liberally helped themselves and their friends to all the choice lots. In later years, tbe unappropriated lots were more remote from the centre of business, although the gradual increase of population was constantly adding to their value. Numerous attempts were then made to filch from the city its more distant tracts of land, and these were often successful. Meanwhile, the legal title of the city itself to all its original estate was disputed, and hosts of rival claimants started up. Conflicting decisions on the subject were given in the courts of law, and all was uncertainty and confusion, violence, ending sometimes in death to the parties, and interminable litigation. The great value of the coveted grounds led to reckless squatterism, and titles by opposite claimants, three or four deep, were pretended to almost every single lot within the municipal bounds. Those who had really made permanent improvements, or who held actual and lucrative possession, might defy the squatter; but the multitude of unimproved land and water lots, and the large tracts around the business part of the city, upon which as yet there was not even a fence, were fair spoils to the resolute invader. No matter what previous title was alleged; all titles were doubtful—except possession perhaps, which was the best. We have, under different dates, noticed at length the speculations of the city guardians in real estate, the Colton grants, Peter Smith sales, and squatter outrages.

The temptation to perpetrate any trick, crime, or violence, to acquire real estate, seemed to be irresistible, when the great returns drawn from it were considered. The reader in the Atlantic States, who may think of the usual cheapness of land in new towns, can scarcely realize the enormous prices chargeable in San Francisco for the most paltry accommodation. We have seen the excessive rents paid in 1849. Four years later, they were nearly as high. The commonest shops, or counting-rooms, in ordinary situations, would rent at from $200 to $400 per month, while larger ones would readily bring $500 and $600. Capacious and handsome stores, auctioneers’ halls, and the like, in desirable localities, would often be held at $1000 per month, or more. The rents of the larger hotels, of the restaurants, coffee saloons, gambling and billiard rooms, and of the finer stores and warehouses, would appear almost incredible to the distant reader. Ordinary stores, offices, and dwelling-houses were rented at equally extravagant sums. One paid away a moderate fortune as a year’s rent for but a sorry possession. The profits of general business were so great that large rents, before they became quite so enormous, were readily given. Capitalists built more and handsomer houses, which were tenanted as soon as ready for occupation. In a couple of years, the building speculator in real estate had all his outlay (which, since labor and materials were so very high, was exceedingly great) returned to him in the shape of rents. Henceforward his property was a very mine of wealth. As rents rose, so did the prices of such property. The richest men in San Francisco have made the best portion of their wealth by the possession of real estate.

For several years, rents and the marketable value of real estate had been slowly, though steadily rising. Towards the close of 1853, they were at the highest. At that period, and generally over a great part of the year named, trade and commerce in San Francisco were unprofitable, and in many cases conducted at a serious loss. An excessive importation of goods, far exceeding the wants of California, and which arose doubtless from the large profits obtained by shippers during the previous year, led to a general fall in prices, and occasionally to a complete stagnation in trade. Then it was found that the whole business of the city seemed to be carried on merely to pay rents. A serious fall in these, and in the price of real estate, more especially of unimproved land, followed this discovery, some notice of which will be given in a subsequent chapter.

As we have said, during 1853, most of the moral, intellectual, and social characteristics of the inhabitants of San Francisco were nearly as already described in the reviews of previous years. There was still the old reckless energy, the old love of pleasure, the fast making and fast spending of money, the old hard labor and wild delights, jobberies and official and political corruption, thefts, robberies and violent assaults, murders, duels and suicides, gambling, drinking, and general extravagance and dissipation. The material city was immensely improved in magnificence, and its people generally had an unswerving faith in its glorious future. Most of them were removed from social trammels, and all from the salutary checks of a high moral public opinion. They had wealth at command, and all the passions of youth were burning within them. They often, therefore, outraged public decency; yet somehow the oldest residenters and the very family men loved the place, with all its brave wickedness and splendid folly.

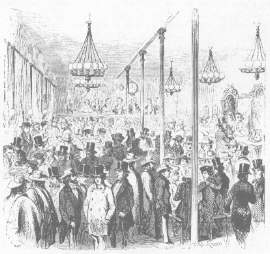

In

previous chapters we have dwelt so fully upon the general practice of gambling

in San Francisco, that it seems unnecessary to do more than merely allude

to it in this portion of the “Annals.” The city has been long made notorious

abroad for this vice. Though not now practised to the large extent of former

years, gambling is still very prevalent among many classes of the inhabitants.

The large public saloons, so numerous in 1849, and immediately succeeding

years, have become few in number at the date of writing (April, 1854).

The chief of them are the “El Dorado,” on the plaza, and the “Arcade” and

“Polka,” in Commercial street. These places still exhibit the old lascivious

pictures on the walls, while orchestral music, excellently performed, continues

to allure the idle, the homeless and familyless, as to a place of enjoyment,

where their earnings are foolishly spent. The cards are often still dealt

out and the wheels turned, or dice thrown, by beautiful women, well skilled

in the arts calculated to allure, betray and ruin the unfortunate men who

become their too willing victims. About the wharves, and in various inferior

streets, there are other public gaming tables, of a lower description,

where the miner particularly is duly fleeced of his bags of dust. There

are also some half a dozen noted houses, of a semi-public character, where

play is largely carried on by the higher order of citizens. In these places,

sumptuous refreshments are provided gratuitously for visitors. The keepers

are wealthy men, and move in the better social circles of the town. At

their “banks,” single stakes are quite frequently made as high as a thousand

dollars, and even five thousand dollars are often deposited upon one hazard.

The “bankers,” however, are not too proud to accept a single dollar stake.

The game played is faro. At such places, very large sums are lost and won;

and many fine fellows have been ruined there, as well in mind as in pocket.

In strictly private circles, there is likewise a great deal of play carried

on, involving large sums. The good old game of “long whist” is ridiculously

slow and scientific for the financial operations of the true gambler, and

the seducing “poker” is what is generally preferred. All these things unhappily

harmonize but too well with the general speculative spirit that marks the

people of San Francisco.

In

previous chapters we have dwelt so fully upon the general practice of gambling

in San Francisco, that it seems unnecessary to do more than merely allude

to it in this portion of the “Annals.” The city has been long made notorious

abroad for this vice. Though not now practised to the large extent of former

years, gambling is still very prevalent among many classes of the inhabitants.

The large public saloons, so numerous in 1849, and immediately succeeding

years, have become few in number at the date of writing (April, 1854).

The chief of them are the “El Dorado,” on the plaza, and the “Arcade” and

“Polka,” in Commercial street. These places still exhibit the old lascivious

pictures on the walls, while orchestral music, excellently performed, continues

to allure the idle, the homeless and familyless, as to a place of enjoyment,

where their earnings are foolishly spent. The cards are often still dealt

out and the wheels turned, or dice thrown, by beautiful women, well skilled

in the arts calculated to allure, betray and ruin the unfortunate men who

become their too willing victims. About the wharves, and in various inferior

streets, there are other public gaming tables, of a lower description,

where the miner particularly is duly fleeced of his bags of dust. There

are also some half a dozen noted houses, of a semi-public character, where

play is largely carried on by the higher order of citizens. In these places,

sumptuous refreshments are provided gratuitously for visitors. The keepers

are wealthy men, and move in the better social circles of the town. At

their “banks,” single stakes are quite frequently made as high as a thousand

dollars, and even five thousand dollars are often deposited upon one hazard.

The “bankers,” however, are not too proud to accept a single dollar stake.

The game played is faro. At such places, very large sums are lost and won;

and many fine fellows have been ruined there, as well in mind as in pocket.

In strictly private circles, there is likewise a great deal of play carried

on, involving large sums. The good old game of “long whist” is ridiculously

slow and scientific for the financial operations of the true gambler, and

the seducing “poker” is what is generally preferred. All these things unhappily

harmonize but too well with the general speculative spirit that marks the

people of San Francisco.

Though there be much vice in San Francisco, one virtue—though perhaps a negative one, the citizens at least have. They are not hypocrites, who pretend to high qualities which they do not possess. In great cities of the old world, or it may be even in those of the pseudo-righteous New England States, there may be quite as much crime and vice committed as in San Francisco, only the customs of the former places throw a decent shade over the grosser, viler aspects. The criminal, the fool, and the voluptuary are not allowed to boast, directly or indirectly, of their bad, base, or foolish deeds, as is so often done in California. Yet these deeds are none the less blamable on that account, nor perhaps are our citizens to be more blamed because they often seek not to disguise their faults. Many things that are considered morally and socially wrong by others at a distance, are not so viewed by San Franciscans when done among themselves. It is the hurt done to a man’s own conscience that often constitutes the chief harm of an improper action; and if San Franciscans conscientiously think that, after all, their wild and pleasant life is not so very, very wrong, neither is it so really and truly wrong as the puritanic and affectedly virtuous people of Maine-liquor-prohibition, and of foreign lands would fain believe.

There

was a small, though steady increase, during the year in the number of female

immigrants. New domestic circles were formed, and the happy homes of old

countries were growing more numerous. Yet while there are very many beautiful,

modest, and virtuous women in San Francisco, fit friends and companions

to honest men, it may be said that numbers of the sex have fallen very

readily into the evil ways of the place. Perhaps the more “lovely” they

were, the more readily they “stooped to folly.” It is difficult for any

woman, however pure, to preserve an unblemished reputation in a community

like San Francisco, where there is so great a majority of men, and where

so many are unprincipled in mind and debauchees by inclination. Not all

women are unchaste whom voluptuaries and scandal-mongers may wish to think

such. The wives and daughters of respectable citizens must be held pure

and worthy. Their presence here confers inestimable blessings upon society.

There are known mistresses and common prostitutes enough left to bring

disgrace upon the place. By the laws of California divorces are readily

obtainable by both husband and wife, one of whom may think him or herself

injured by the unfaithful or cruel conduct of the other, and who, perhaps,

disliking his or her mate, or loving another, may wish to break the bonds

of wedlock. Divorces are accordingly growing very numerous here, and have

helped to raise a general calumny against the sex. Some of the newspapers

now regularly give, without comment these “matrimonial jars” as pieces

of news in their columns, facetiously placing “divorces” between the ordinary

lists of “marriages” and “deaths.” Like the male inhabitants, the females

of San Francisco are among the finest specimens, physically, of the sex,

that can anywhere be seen.

There

was a small, though steady increase, during the year in the number of female

immigrants. New domestic circles were formed, and the happy homes of old

countries were growing more numerous. Yet while there are very many beautiful,

modest, and virtuous women in San Francisco, fit friends and companions

to honest men, it may be said that numbers of the sex have fallen very

readily into the evil ways of the place. Perhaps the more “lovely” they

were, the more readily they “stooped to folly.” It is difficult for any

woman, however pure, to preserve an unblemished reputation in a community

like San Francisco, where there is so great a majority of men, and where

so many are unprincipled in mind and debauchees by inclination. Not all

women are unchaste whom voluptuaries and scandal-mongers may wish to think

such. The wives and daughters of respectable citizens must be held pure

and worthy. Their presence here confers inestimable blessings upon society.

There are known mistresses and common prostitutes enough left to bring

disgrace upon the place. By the laws of California divorces are readily

obtainable by both husband and wife, one of whom may think him or herself

injured by the unfaithful or cruel conduct of the other, and who, perhaps,

disliking his or her mate, or loving another, may wish to break the bonds

of wedlock. Divorces are accordingly growing very numerous here, and have

helped to raise a general calumny against the sex. Some of the newspapers

now regularly give, without comment these “matrimonial jars” as pieces

of news in their columns, facetiously placing “divorces” between the ordinary

lists of “marriages” and “deaths.” Like the male inhabitants, the females

of San Francisco are among the finest specimens, physically, of the sex,

that can anywhere be seen.

The subject of females naturally introduces that of housekeeping; and we accordingly take occasion here to mention a few items regarding the expenses of a family in San Francisco at the beginning of 1854. The wages of female servants are from fifty to seventy-five dollars per month. Wood costs fifteen dollars per cord; coal, per hundred-pound sack, three dollars; and the same, per ton, delivered, fifty dollars. At market, the best cuts of beef, pork, and mutton, are thirty-seven and a half cents per pound; venison is thirty-one cents; salmon, twenty-five cents; best fresh butter, one dollar; second quality of the same, seventy-five cents; Goshen butter, fifty cents; fresh eggs, one dollar and twenty-five cents per dozen; Boston eggs, seventy-five cents per dozen ; turkeys, six to ten dollars each; wild geese, or ducks, one dollar each; chickens, two dollars and fifty cents to three dollars each; quails, six dollars per dozen; potatoes, two to three cents per pound; cabbages, twenty-five cents a head; cauliflowers, thirty-seven to fifty cents each; turnips, parsnips, and beets, one dollar per dozen; milk, twenty-five cents per quart. Rents of dwelling-houses vary from fifteen or twenty dollars per month, for a single small apartment, up to five hundred dollars per month, or what more one will, if a stylish mansion must be had.

The

multitude of foreign races in San Francisco, French, Germans, and Hispano-Americans,

with all their different complexions, tongues, modes of dressing, amusements,

manner of living, and occupations, so different from those of the Americans,

and the numerous half-helot tribes of Chinese, Lascars, and negroes, who

are still more unlike our people in their natural and acquired characteristics,—all

make the city the most curious Babel of a place imaginable. There are many

less, though still considerable shades of difference existing among Americans

themselves, who are drawn from all corners of the Union, and between them

and the various distinctive natives of the British Isles. Again, there

are numerous individuals from European countries, not yet named, such as

Italians, Spaniards, Greeks, Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and others. All these

peoples, differing in language, blood, and religion, in color and other

physical marks, in dress and personal manners, mental habits, hopes, joys,

fears, and pursuits, and in a multitude of nice particulars, stamp upon

San Francisco a peculiarly striking and motley character. The traveller

and the student of mankind will meet here with specimens of nearly every

race upon earth, whether they be red, yellow, black, or white. Many of

them are still seen in their national state, or at least with the broadest

traces of their native qualities. In some respects, however, perhaps most

of them have been deeply impressed by the genius of the place. Such show

the peculiar mark of Young America on the Pacific—the Californian, and

especially the San Franciscan “go-ahead” disposition. Let the immigrant

be from what country and of what personal temperament and character he

may, a short residence here will make him a shrewder and more energetic

man, who works harder, lives faster, and enjoys more of both intellectual

and sensuous existence than he would be able to do in any other land. On

any occasion of public excitement, such as a fire, a fight, an indignation

or filibustering meeting, or the like, there is gathered together a multitude,

which cannot be paralleled in any other place, of stalwart, bearded men,

most of whom are in the early prime of life, fine, healthy, handsome fellows.

The variety and confusion of tongues and personal characteristics, the

evident physical strength, reckless bravery, and intelligence of the crowd,

make a tout ensemble that is very awful to contemplate. Turn these

men into an angry mob, armed, as at all times most of them secretly are,

with revolvers and bowie-knives, and a legion of drilled soldiers could

scarcely stand before them. These youthful giants are the working spirits

of San Francisco, that have given it a world-wide fame for good and evil.

The

multitude of foreign races in San Francisco, French, Germans, and Hispano-Americans,

with all their different complexions, tongues, modes of dressing, amusements,

manner of living, and occupations, so different from those of the Americans,

and the numerous half-helot tribes of Chinese, Lascars, and negroes, who

are still more unlike our people in their natural and acquired characteristics,—all

make the city the most curious Babel of a place imaginable. There are many

less, though still considerable shades of difference existing among Americans

themselves, who are drawn from all corners of the Union, and between them

and the various distinctive natives of the British Isles. Again, there

are numerous individuals from European countries, not yet named, such as

Italians, Spaniards, Greeks, Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and others. All these

peoples, differing in language, blood, and religion, in color and other

physical marks, in dress and personal manners, mental habits, hopes, joys,

fears, and pursuits, and in a multitude of nice particulars, stamp upon

San Francisco a peculiarly striking and motley character. The traveller

and the student of mankind will meet here with specimens of nearly every

race upon earth, whether they be red, yellow, black, or white. Many of

them are still seen in their national state, or at least with the broadest

traces of their native qualities. In some respects, however, perhaps most

of them have been deeply impressed by the genius of the place. Such show

the peculiar mark of Young America on the Pacific—the Californian, and

especially the San Franciscan “go-ahead” disposition. Let the immigrant

be from what country and of what personal temperament and character he

may, a short residence here will make him a shrewder and more energetic

man, who works harder, lives faster, and enjoys more of both intellectual

and sensuous existence than he would be able to do in any other land. On

any occasion of public excitement, such as a fire, a fight, an indignation

or filibustering meeting, or the like, there is gathered together a multitude,

which cannot be paralleled in any other place, of stalwart, bearded men,

most of whom are in the early prime of life, fine, healthy, handsome fellows.

The variety and confusion of tongues and personal characteristics, the

evident physical strength, reckless bravery, and intelligence of the crowd,

make a tout ensemble that is very awful to contemplate. Turn these

men into an angry mob, armed, as at all times most of them secretly are,

with revolvers and bowie-knives, and a legion of drilled soldiers could

scarcely stand before them. These youthful giants are the working spirits

of San Francisco, that have given it a world-wide fame for good and evil.

When the early California pioneer wandered through the city, and contrasted the lofty structures which he saw on all sides; the broad, level, and bustling streets, the chief of them formed where once rolled the long swell of the sea; the great fire-proof warehouses and stores, filled with the most valuable products of all lands; the wharves, crowded with the largest and finest vessels in the world; the banks, hotels, theatres, gambling saloons, billiard-rooms and ball-rooms, churches, hospitals and schools, gin palaces and brick palaces; the imposing shops, within whose plate-glass windows were displayed the richest assortment of articles of refined taste and luxury; the vast amount of coined money incessantly circulating from hand to hand; the lively and brilliant array of horse and carriage riders; the trains of lovely women, and the crowds of well-dressed, eager men, natives of every country on the globe, most of whom were in the flower of life, and many were very models of manly or of feminine beauty—for the cripple, the hunchback, the maimed and deformed find not their way hither—when the veteran immigrant contrasted these things with what had been only a few years before, he could scarcely persuade himself that all the wonders he saw and heard were aught but a dream. The humble adobes, and paltry wooden sheds; the bleak sand hills, thinly dotted with miserable shrubs; the careless, unlettered, ignorant, yet somewhat gallant Californians; the few ragged Indians and fewer free white men; the trifling trade and gentle stir of the recently founded settlement of Yerba Buena, where coin was a curiosity; the great mud fiat of the cove with its half dozen smacks or fishing boats, canted half over at low tide, and perhaps a mile farther out, a solitary square-rigged ship, the peaceful aspect of the village of the olden time—all flashed across the gazer’s memory. Before one hair had turned gray, ere almost the sucking babe had learned his letters, the magic change had been accomplished. Plutus rattled his money bags, and straightway the world ran to gather the falling pieces. The meanest yet most powerful of gods waved his golden wand, and lo! the desert became a great city. This is an age of marvels; and we have seen and mingled in them. Let the pioneer rub his eyes: it is no mirage, no Aladdin’s palace that he sees—but real, substantial tenements—real men and women—an enduring, magnificent city.

When the later pioneer took his sentimental stroll, memory only recalled the frantic scenes of the memorable ‘49—a period that never can be forgotton by those who saw and shared in its glorious confusion. The lottery of life that then existed; the wild business and wilder amusements; the boundless hopes; the ingenious, desperate speculations; the fortunes made in a day and lost or squandered nearly as quickly; the insatiable spirit of play; the midnight orgies; the reckless daring of all things; the miserable shanties and tents; the half-savage, crime and poverty-stained, joyous multitudes, who had hastened from the remotest parts of the earth, to run a terrible career, to win a new name, fortune and happiness, or perish in the struggle; the commingling of races, of all ranks and conditions of society; the incessant rains and deep sloughs in the streets, with their layers, fourteen feet deep, of hams, hardware, and boxes of tobacco, where among clamorous and reckless crowds people achieved the dangerous passage; the physical discomforts; the sickness, desertion, despair and death of old, heart-broken shipmates and boyhood companions, whom remorse could not bring again to life, nor soothe the penitent for his cruel neglect; the rotting, abandoned fleets in the bay; the crime, violence, vice, folly, brutal desires and ruinous habits; the general hell (not to talk profanely) of the place and people—these things, and many of a like saddening or triumphant nature, filled the mind of the moralizing “forty-niner.”

If these pioneers—and like them every later adventurer to California

may think and feel, for all have contributed something to the work—lent

themselves to the enthusiasm and fancy of the moment, they might be tempted

with the Eastern king to proudly exclaim, and as truly: Is not this

great Babylon that I have built, for the house of the kingdom, by the might

of my power, and for the honor of my majesty? Many obstacles, both

of a physical and moral nature, have been encountered and gradually overcome

before the grand result was obtained. Hills were removed and the deep sea

filled up. Town after town was built, only to be consumed. Great fires

destroyed in one hour the labor of months and years. Commercial crises

and stagnation in trade came to crush individuals. The vagabonds and scoundrels

of foreign lands, and those too of the federal Union, were loosed upon

the city. Robbers, incendiaries and murderers, political plunderers, faithless

“fathers” and officials, lawless squatters, daring and organized criminals

of every description, all the worst moral elements of other societies,

were concentrated here, to retard, and if possible finally destroy the

prosperity of the place. All were successively mastered. Yet the excesses

of the “Hounds,” the scenes of the great fires, the action of the “Vigilance

Committee,” and the crimes that created it, the multitude of indignation

meetings and times of popular strife, the squatter riots, and the daily

occurrence of every kind of violent outrage—whatever was most terrible

in the history of the city, will ever be remembered by the early citizens.

Some of the worst of these things will never again occur; and others are

being yearly modified, and deprived of much of their old frightful character.

For the honest, industrious and peaceable man, San Francisco is now as

safe a residence as he can find in any other large city. For the rowdy

and “shoulder-striker,” the drunkard, the insolent, foulmouthed speaker,

the quarrelsome, desperate politician and calumnious writer, the gambler,

the daring speculator in strange ways of business, it is a dangerous place

to dwell in. There are many of such characters here, and it is principally

their excesses and quarrels that make our sad daily record of murders,

duels, and suicides.