The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

1854.

JANUARY 9th.—Large public meeting held, of parties chiefly interested, at the Merchants’ Exchange, to consider the effect of certain late decisions by the Supreme Court, which had established the constitutionality of the State Revenue Act of 15th May, 1853. Many of the provisions in this Act, such as the heavy license duties laid upon auctioneers and others; the duty of one per cent. chargeable on goods and real estate exposed to auction; that of “ten cents upon each one hundred dollars of business estimated to be transacted” by bankers, and dealers in exchanges, stocks, gold dust, and similar occupations; and particularly the tax of sixty cents per one hundred dollars laid upon “consigned goods,” were considered to be unequal, oppressive and unconstitutional in their operation. The following were declared to be “consigned goods” within the meaning and intent of the Act: “All goods, wares, merchandise, provisions, or any other property whatsoever, brought or received within this State (California) from any other State, or from any foreign country, to be sold in this State, owned by any person or persons not domiciled in this State.” It was estimated, that if the tax upon “consigned goods” were enforced, an annual burden of $300,000 would be laid upon shippers to the port. In like manner, the tax upon the sales of personal property, to say nothing of those of real estate, would form a burden of $125,000 annually; while the duties leviable upon the banking class would be so monstrous that their business could not be carried on. The parties against whom these duties were leviable, refused to pay them; and accordingly actions had been raised by the proper officials on the part of the State to try their legality. The Supreme Court of California had just established that point in favor of the State, but those who were affected by the obnoxious provisions of the Revenue Act still refused to acknowledge their validity.

At the meeting above mentioned (Alfred Dewitt, chairman), resolutions were unanimously passed—condemning the objectionable parts of the Revenue Act as “flagrantly oppressive and unjust “—declaring that they never would be submitted to, until “all lawful and proper methods of redress should be exhausted “— instructing counsel to move for a rehearing of the case before the Supreme Court, and to prosecute all appeals that could be made to the Supreme Court of the United States—that a memorial should be prepared and laid before the Legislature praying for a repeal of the Act complained of—and that Various committees should be appointed to collect subscriptions from the citizens and carry out the views expressed in the resolutions. Such committees were accordingly chosen, and the meeting separated.

While we write, the matters complained of remain in an unsatisfactory and unsettled state. The law has not been enforced and there is considerable doubt whether it ever can or will be. The subject is one of great importance to the prosperity of San Francisco, and has added strength and bitterness to the charges often made against the Legislature, that it consults in its proceedings more the interests of the mining and agricultural than of the commercial portion of the State.

JANUARY 18th.—Run upon Adams & Co., bankers. This commenced on the evening of the 17th, and continued all next day. It arose from the circumstance that the name of Adams & Co. did not appear among the published list of those who had exported gold by the semi-monthly steamers. The firm named had actually shipped their usual quantity of specie, but this fact was not known to the public. Upwards of a thousand of the smaller depositors took the alarm, and hastened to withdraw their money. The house, whose solvency was undoubted by large capitalists, was well able to meet the unexpected demand, and, by the close of business on the 18th, had paid out $416,000. In a short time afterwards, their old customers gladly re-deposited the sums so hastily drawn. We take this opportunity to make a few remarks upon banking in San Francisco.

There are no chartered banks in California. By the Constitution, no corporation for banking purposes can exist in the State, nor is any species of paper circulation admitted. The first regular banking house in San Francisco was established on the 9th day of January, 1849, under the firm of Naglee & Sinton. Their “Exchange and Deposit Office” was on Kearny street, fronting the plaza, in the building known as the Parker House, and on the site of the present City Hall. Mr. Sinton soon retired from the firm. The business was then continued by Mr. Naglee until the run already noticed, on the bank, in September 1850, when he closed. Prior to the opening of this office, deposits were made with the different mercantile houses having safes, such as Ward & Co.; W. H. Davis; Mellus, Howard & Co.; Dewitt & Harrison; Cross & Co.; Macondray & Co., and others. This was not only the case at San Francisco, but at places in the interior. At Sutter’s Fort, and afterwards at Sacramento City, the principal houses of deposit were S. Brannan & Co.; Hensley, Reading & Co.; and Priest, Lee & Co.

As the population increased, the work of receiving and paying out deposits became so great, that the necessity of houses devoted especially to the business began to be felt; and these accordingly were soon established. At the close of 1849, the following houses were in operation:

Henry M. Naglee, established January 9th, 1849.

Burgoyne & Co, established June 5th, 1849.

B. Davidson, established about September 1849.

Thomas G. Wells (afterwards Wells & Co.), established October 1849.

James King of William, established December 5th, 1849.

Previous to the discovery of gold and the consequent rapid influx of population, there was but very little coin in the country, and that little mostly in the towns of Monterey, San Francisco, San Diego and Los Angeles. Payments throughout the country were frequently made in cattle, hides, &c. The gentleman,— an eminent banker in San Francisco,—from whom we have obtained these and the following facts upon banking, has seen an account, credited, “by two cows in full,” for a physician’s bill of $20. This was in 1847, and near Los Angeles. After the discovery of gold, that substance in its natural state became the currency, and passed in all business operations at $16 per ounce. The scarcity of coin was so great about and for some time after that period, and the demand for it to pay custom-house duties so urgent, that gold dust was frequently offered at $8 and $10 per ounce. This was particularly the case in the months of November and December, 1848. During the same months in 1849, the bankers’ rates were as follows: for grain dust, $15.50 to $15.75 per ounce; and for quicksilver dust, $14.50 to $14.75 per ounce. This was when coin was paid out for the dust. When the bankers received it in deposit, they valued it at $16 per ounce and repaid it at the same rate.

D. J. Tallant (now Tallant & Wilde), opened his banking house in February, 1850; and Page, Bacon & Co., and F. Argenti & Co., theirs in June of the same year. Subsequently several others were established. At this date (April, 1854), the following houses are in operation:—Burgoyne & Co., established June 5th, 1849; B. Davidson, September, 1849 ; James King of Wm., December 5th, 1849; Tallant & Wilde, February, 1850; Page, Bacon & Co., June, 1850; Adams & Co. (first as express agents, now express and banking house); Palmer, Cook & Co.; Drexel, Sather & Church; Robinson & Co. (savings bank); Sanders & Brenham; Carothers, Anderson & Co.; Lucas, Turner & Co.

JANUARY

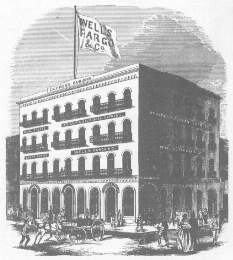

20th.—The “Express Building,” north-east corner of Montgomery and California

streets, completed, the foundations having been laid in September, 1853.

This is another of Mr. Samuel Brannan’s magnificent street improvements.

The building is seventy-five feet high, having four stories and a basement,

and has a front on Montgomery street of sixty-eight feet, and on California

street, of sixty-two and a half feet, and cost, exclusive of the land,

$180,000. The lot is valued at $100,000. Wells, Fargo & Co., bankers

and express agents, and Pollard & Co., real estate and money brokers,

occupy the lower floor. In the fourth story the society of California Pioneers

have their hall and secretary’s office. The remainder of the building is

used for a variety of business purposes.

JANUARY

20th.—The “Express Building,” north-east corner of Montgomery and California

streets, completed, the foundations having been laid in September, 1853.

This is another of Mr. Samuel Brannan’s magnificent street improvements.

The building is seventy-five feet high, having four stories and a basement,

and has a front on Montgomery street of sixty-eight feet, and on California

street, of sixty-two and a half feet, and cost, exclusive of the land,

$180,000. The lot is valued at $100,000. Wells, Fargo & Co., bankers

and express agents, and Pollard & Co., real estate and money brokers,

occupy the lower floor. In the fourth story the society of California Pioneers

have their hall and secretary’s office. The remainder of the building is

used for a variety of business purposes.

An unusual degree of cold was experienced in San Francisco for several days about this time, exceeding any thing that “the oldest inhabitant” recollected. To-day, ice, in some places an inch thick, was formed in the streets. Within doors, the water in pitchers was generally frozen. At two o’clock P.M., icicles a foot in length hung from the roofs of houses on which the sun had been shining all day. The small lagoons around the city were frozen over, and excellent skating was had on ponds near the mission. The hills in Contra Costa and near the mission had their summits covered with snow.

There is a whimsical notion among native Californians, that the coming of “these Yankee devils” has completely changed the character of the seasons here, the winter months especially being, it is believed, now wetter and colder than before the American advent. The excessive rains of the winters of 1849-50, and 1852-53, lent some fanciful support to the Californian faith. The frosts and snows of January, 1854, seemed to corroborate it. The winter of 1850-51 on the other hand, was warm, dry and agreeable, to a degree seldom experienced even in the usually mild climate of California.

We have alluded here particularly to these facts, from the circumstance that San Francisco is peculiarly dependent on the weather, inasmuch as the character of the latter materially affects the production of gold in the mining regions. Too much water or too little, at particular seasons of the year, will equally prevent mining from being very successful. In summer, the miners are generally engaged at what are called the “wet diggings,” in or beside the beds of rivers, when these are low. There, unexpected rains and consequent floods would ruin all their prospects. At other periods of the year, when the rivers are full, the miners work upon the “dry diggings,” upon plains, uplands, and in ravines, which are often at a considerable distance from any stream. As, however, large quantities of water are required for the purpose of washing the auriferous earth, rains then become necessary. In many districts at certain seasons, rich “dry diggings” have been prematurely deserted for want of sufficient supplies of water. To rectify this want, large rivers have been turned, at great labor and expense, from their course, and their waters led by artificial channels to whatever places they may be in demand, those persons using the water paying certain rates for the privilege. The water companies, many of which possess large capitals, form peculiar features of the mining districts. They, however, can assist but a small portion of the whole number of “dry diggings,” and copious rains are indispensable for the rest. The rains in the early part of the winter of 1853-54 had been very slight; and great inconvenience was experienced at the mines for want of the usual supplies of water. The rivers were too full for “wet diggings,” and the plains and hill sides too dry for “dry diggings.” The production of gold was therefore materially lessened, and this fact, joined with a glut of imported goods, and heavy charges upon business, particularly the enormous rents, had produced much commercial distress about this period in San Francisco. In the spring of 1854, abundant rains fell, which set the miners all busy at profitable work, and it was expected by many that commerce would consequently revive. Other circumstances, however, prevented that desirable event, which shall be noticed in the next chapter.

FEBRUARY.—Publication of the San Francisco Directory for 1854. This is only noticed from the circumstance of its being much the fullest and most reliable directory that had appeared here. It contained the names and addresses of about twelve thousand persons; and, in an Appendix, a very great deal of useful and curious information about the city. The canvasser and compiler was Frank Rivers. It was published by LeCount & Strong.

FEBRUARY 8th.—Loss of the clipper ship San Francisco, from New York to this port. This was a fine new ship of large tonnage, whose cargo was valued at $400,000. In beating through the entrance to the bay, she missed stays and struck the rocks on the north side, opposite Fort Point. This was nearly at the spot where the English outward-bound ship Jenny Lind, from the same cause, was wrecked a few months before. The “Golden Gate” is narrow, but the channel is deep and perfectly safe, if only its peculiarities be known and attended to. The loss of the ships named was supposed to be more attributable to the ignorance or neglect of their pilots than to any natural dangers in the place at the time. If it were obligatory on masters of sailing vessels, not small coasters, to employ steam-tugs to bring their ships from outside the Heads into the harbor, such accidents as these could not occur. It appears that twenty-three large vessels have either been wrecked, stranded, or seriously injured in San Francisco Bay since 1850. This number is exclusive of any accidents occurring to vessels at anchor in the roadsteads, or lying at the wharves. The total losses in the harbor, since 1850, are estimated to have exceeded a million and a half dollars.

The wreck of the San Francisco was attended by circumstances very discreditable to some of the people in and around the city. So soon as the occurrence was known, a multitude of plunderers hastened to the wreck, and proceeded to help themselves from the ship’s hold. It was in vain that the owners or their agents attempted to drive them away. Some two hundred dare-devil Americans, nearly all armed with the usual weapons, five or six-shooters and bowie knives, were not to be frightened by big words. They stood their ground, and continued to take and rob as they pleased, plundering from each other as well as from the ship. It was said that even some of the soldiers from the presidio crossed the strait, and became wreckers themselves. Then a storm came, and scattered and capsized the deep-laden boats that were bearing the spoil away. Some were carried out to sea, and were lost; others were swamped close beside the wreck and a few of their passengers were drowned. The number of lives lost could not be exactly ascertained, although it was supposed that, at least, a dozen persons must have perished in the midst of their unhallowed occupation. There were no lives lost of those connected with the San Francisco. She was sold after the wreck, as she lay, her contents included, for $12,000. A short time afterwards, and when some of the lighter parts of the cargo had been removed, the ship went to pieces, as had been the case with the Jenny Lind, before her.

FEBRUARY 11th.—The city was first lighted with coal gas on the evening of this day. The occasion was celebrated by several hundred citizens at a banquet given by the trustees of the “San Francisco Gas Company,” in the Oriental Hotel. Already about three miles of pipes were laid in the streets, to be increased as the public accommodation required. At first, only a few of the principal streets and some of the leading hotels and large mercantile establishments were lighted with gas; but every day the number is increasing. The “Metropolitan” theatre, a few weeks after this date, adopted the new light. It will, of course, soon become general, and prove a great benefit to the city. When in addition to gas, the leading street-grades are completed, the streets themselves properly paved with stone, and fresh water introduced by the “Mountain Lake Water Company,” San Francisco will present an appearance equally agreeable and striking to those who recollect the dangers and troubles of traversing its old swampy paths on dark nights. The price charged by the company for the gas was $15 per thousand feet. In regard to this rate, J. M. Moss, the president of the company, remarked at the entertainment above alluded to, that, considering that in San Francisco the price of coal was $36 to $40 per ton—money, 36 per cent. per annum—labor, $6 to $7 per day—gas was furnished here 50 per cent. lower than in New Orleans, and about 20 per cent. lower than in New York. The San Francisco Gas Company was incorporated with a capital of $450,000, and their works were commenced in November, 1852. These are situated on Front street, one hundred and thirty-seven and a half feet, extending from Howard to Fremont street, along which streets they have a depth of two hundred and seventy-five feet. The company was organized with the following officers:—President—Beverley C. Sanders; Vice-President—J. Mora Moss; Secretary—John Crane; Trustees—B. C. Sanders, J. M. Moss, James Donahue, John H. Saunders, John Crane.

The first street lamps in San Francisco were erected in Merchant street, by Mr. James B. M. Crooks, in October, 1850. They were lighted with oil, and to be paid for by private subscription. The same gentleman had also completed the erection of ninety lamps, on the 20th of February, 1852, on Montgomery, Clay, Washington and Commercial streets, to be paid for in a similar manner. These, with the exception of four posts, were all destroyed by the fire of the 4th of May following. In the autumn of 1852, the common council contracted with Mr. Crooks to light the city within the limits of Battery, Kearny, Jackson and California streets. This contract was carried out until the introduction of gas as above related, by a contract made with Mr. James Donahue for the “San Francisco Gas Company.”

FEBRUARY 17th.—A serious riot took place this afternoon at the Mercantile Hotel, when the policemen in their endeavors to perform their duty by apprehending the rioters, were maltreated by them, and severely injured.