The Annals of San Francisco

The Annals of San Francisco

ONCE a fortnight, at the beginning and middle of every month, San Francisco which is never without some feverish excitement, gets gradually worked up to a crisis. Different places have also their occasional periods of intense interest. What in other countries may be the annual fair to a village belle, a great saint's day of obligation to devout Roman Catholics, the solitary "cheap pleasure trip" to the artisan who has toiled and moiled unceasingly for a twelvemonth, the last day of grace to a tottering merchant who must meet his bill—but what need is there of comparisons? STEAMER-DAY in San Francisco stands alone; it is sui generis. Every body, man, woman, and child, native and foreigner, merchant and miner, general dealer, laborer, and non-descript adventurer, old resident, and recent immigrant—every body is deeply interested in this day. Mails in the Atlantic cities start oftener, and affect only particular sections of the community; but the great èastern mails that leave San Francisco depart at long intervals, while they directly concern all classes. The people who live here are not yet independent, either in business or in home and affectionate feelings, of the connections of their native countries. Hence, an immense amount of correspondence is written and forwarded every two weeks.

Some days before the 1st or the 16th of the month, the merchant, who must send returns for the goods he has received, and perhaps sold, begins to consider how best he can "raise the wind." He is not a Prospero, who, by waving his wand, consulting his book, and muttering a few conjurations, can command the elements; but he summons his "faithful Ariel," his managing clerk, and the two take a long spell of a different description. Daily, hourly, obstinate debtors are dunned; and are alternately beseeched, wheedled and bullied, to come down with the dust—the one precious product and export of Califiania. One's own funds are failing, and money every where has suddenly and alarmingly become scarce. Debtors are doubtful, and no credit is given the unfortunate cash-hunter himself. Yet money must be had for steamer-day. This is essential to the merchant's honor and his continuance in business. Cash bargains are therefore harried through at any sacrifice, and temporary loans effected, upon tangible security always, at usurious rates—from four to five, up to tea or twelve per cent. per month. Every means is taken to collect a given sum. While the merciless creditor assails his shuffling debtor, he himself turns a dull ear to reproaches, entreaties and threats of his own creditors and dunners. Every man for himself in such matters. All the businessmen in San Francisco are bustling about; every body is abusing another for dilatoriness in making payments. What should have been paid before last steamer-day not yet forthcoming!—what was a cash transaction two days ago not yet settled for! Why, it was shameful, unbusiness-like, atrocious conduct! Where did such people expect to go to when they died? So the angry dunner says to one neighbor, and so another speaks to the poor enraged man a few minutes afterwards. The agony and the "hope deferred" of making up the required sum continue to grow in intensity until the last moment that bank, post, and express arrangements permit the remittance to be made. When the gun of the departing steamer is heard, the merchant feels once more at ease. His excited nervous system becomes relaxed; and for another week, or ten days, he cares not though he receives not a cent. He smiles again on his delinguent debtor; they drink lovingly together, and exchange segars, and chat and joke, in the most friendly manner, of their individual troubles and throes in providing for the dread steamer-day. There is little business done the day before the mail leaves, and none on the forenoon of the day of its departure. Not only is time consumed in attending to the indispensable remittances, but numerous business letters must be answered, the state of the markets described, account sales made out, suggestions given to foreign merchants for particular shipments, and new orders sent on one's personal account. The business letters alone of an extensive mercantile house must closely occupy the time of the heads of the firm for at least a whole day before the mail is closed.

The purely business letters may be the most urgent and pecuniarily important communications, but those between the resident and his friends at home are the most interesting. Many residing here have left wives and families in far distant countries. To such the opportunity is invaluable of telling of their various movements, of their speculations, hopes and fears, their health and comforts, and to express all their affectionate wishes and love towards those most dear to them. But besides the married and family man, all have more or fewer acquaintances and dear friends whom they wish should know of their "whereabouts." When emigrants leave home to settle permanently in a new land, they very soon cease to feel interest in their native place and old friends, and gradually give up the first habit of communicating by letter with them. But many of the San Franciscans have the surety of speedily rejoining the friends and country they had left, whilst most of them hope and expect that they will be enabled to do so in a few years at farthest. Hence, all these find it their interest, as they feel it their pleasure, to keep up a familiar correspondence with the mother country. The answers that will appear by and by to their several communications will be eagerly looked f0r, and perused over and over again. To continue to receive such interesting epistles, they must be faithfully acknowledged. Replies and other letters are accordingly multiplied for each mail. With many people, the entire day before the sailing of the steamer is consumed in writing these. No wonder that the occasion is looked forward to with much interest.

But it is not merely epistolary communications and the necessity of remitting that give lifelike interest and excitement to steamer-day. Always two, and often three, large vessels leave upon that occasion, conveying together from a thousand to sometimes nearly two thousand persons. That alone is an immense body of people, who are naturally very much excited by thoughts of the long passage, and the peculiar circumstances attending their departure. Besides these it may be supposed that at least thrice the same number of persons are diretly interested as the nearest friends of the actual passengers, while the whole city entertains some kind of curiosity as to who are leaving and a general feeling of interest on the subject. Numbers have come from the mines and interior towns to take their departure from San Francisco; and these crowd the hotels and boarding-houses for a few days until the steamer sails. From every large lodging-house there is somebody departing, while in almost every house there are companions and confidants of those leaving. These must commune and prepare; they must drink, smoke and palaver; buy and interchange gifts, and make solemn promises of future communications. All is eagerness and excitement, on both sides, until steamer-day, has come and gone.

Follow the crowd on the eventful day. The merchant has dispatched his letters, his expresses, his remittances, and has now a little leisure. So he takes a stroll down to the pier-head to see some old friends off. The mail-bags are closed, and the anxious correspondent with home may now begin to count the weary weeks and days before he receives fond answers. He also can spare an hour, and dreamily wends his way to mark the noble ship set sail that bears the mail, his letters included. The express wagons that bear two millions of treasure are on their way. The loafer and the compulsorily idle man likewise attend, because they are fond of a show and have nothing else to do. General business is in some measure suspended, or lazily conducted until the steamer is actually gone. The baggage of the passengers, which is seldom very much, is being conveyed on board. Same adieus have already taken place; but most are to be made upon the wharf or on the ship's deck. The mail boat for Panama starts from Pacific street wharf; the opposition vessel, for San Juan del Sud (Nicaragua route), from the wharf at Jackson street. Let us take our stand on the latter. As it happens, the ship is neither the largest nor the finest of the line, yet it is an excellent boat notwithstanding, and we have a friend on board who is leaving for the east.

The "Brother Jonathan" is already beginning to be crowded. Above and below, passengers with flushed faces and scarcely steady steps are prowling among the heaps of packages and boxes, searching for their own. They bustle about, and after some thick speechifying and unnecessary gestures discover their "bunks," and secure their "traps" as closely as possible. All is confusion. Something is sure to be forgotten at the last moment; something of the utmost consequence is still to be done. There is neither time nor fit person to do the thing needful; and the unhappy passenger dare not leave the ship for an instant, lest she sail without him. There is, however, no real danger of that, though there is so much fear. One half of the passengers are still on the wharf, talking fast and hurriedly with friends, and preparing to take the last farewells. On board, a majority of the people are those who have only come to see the emigrant off. Small groups cluster wherever there is standing room on the different decks. The bottle is produced, and the last drop taken; champagne freely flows among the state-cabin nobs, and rum or ready-mixed bottled cocktails among the snobs over all the ship. But we forget—in California happily all are equal and independent, and there can be neither the pure snob nor nob, where originally all came alike penniless, and nearly all who make money do it "by the sweat of their brow." Well, some continue poor, and some wax wealthy. Some have been industrious and thrifty, enterprising and successful: these soon grow rich. Others have been lazy and idle, perhaps weak, sick or incapable, or they have spent their gains in intemperance, gaming or debauchery; and these will never make or long keep a fortune in any country. Among them all, some can and do pay for state-cabins; others can, but will not; a considerable number ought not, but do; while the most cannot, and consequently do not. All, however, are rejoiced to hold their friends to the last, and seek to show their joy in various ways—in cheerful discourse and in drinks, in a warm shake of the hand, a half-stifled sigh and a heartfelt look.

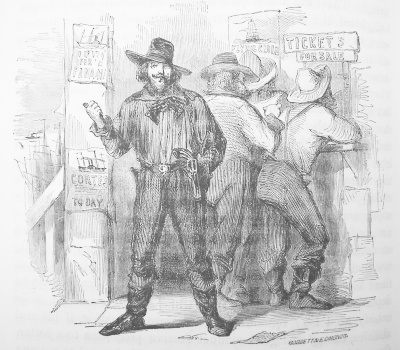

Near the forecastle there is a group of shaggy-haired and bronzed-faced though good-looking fellows. These are going home with the profits of a successful trip to the mines. They still wear the old red or blue woollen shirt, the battered hat and the belt of the digger. Somewhere hidden about their persons are certain little bags with fifty or a hundred ounces of the "dust," ay, or perhaps five hundred ounces, for aught that a stranger could tell. They conceal likewise a five or six-shooter, or a brace of pistols, capped and headed with ball, or it may be a formidable blade that makes the blood run cold to touch. Sometimes indeed these weapons are openly displayed. Such men shall not be robbed of their hard won treasure without making some effort to save it, or they will have dire revenge at all events for their loss. There may not be much risk, once on board, and on the fair way to a law-protected land; but habit is second nature, and still still they bear the old faithful companions of their toils and dangers. These determined "b'hoys" are the fortunate and careful miners. Beside them are others of a different stamp. The hollow cheek, sunken eye and feeble gait tell of broken constitutions. Sickness seized the hapless adventurer at the mines, just when the foundation of his "pile" was being laid famously. There was a struggle for a little while between avarice and the longing for health and life. Disease threatened the latter in unmistakable symptoms. The patient was unwillingly forced to relinquish his best hopes, and drag himself to town for advice and aid. He continued weak, and was becoming poor—for doctors' bills are heavy in California. So while he could still muster strength and pay his passage, he resolved to go home, to see old friends, his mother and the sweetheart he had been betrothed to, and then "go sleep with his fathers."

The

mining class form a large portion of the fore-cabin and steerage passengers.

Many of these, since their first coming to California, had visited "the

States" on previous occasions. They took seasons of working at the

mines, and passed the intervals in making jaunts home and enjoying themselves

with their families and friends. When the annual period came round, like

regular birds of passage, they migrated once more to the foot-hills and

valleys of the Sierra Nevada, to labor lustily for so many months, accumulate

another nice little "heap," then descend upon San Francisco, to leave it

shortly afterwards upon steamer-day.

The

mining class form a large portion of the fore-cabin and steerage passengers.

Many of these, since their first coming to California, had visited "the

States" on previous occasions. They took seasons of working at the

mines, and passed the intervals in making jaunts home and enjoying themselves

with their families and friends. When the annual period came round, like

regular birds of passage, they migrated once more to the foot-hills and

valleys of the Sierra Nevada, to labor lustily for so many months, accumulate

another nice little "heap," then descend upon San Francisco, to leave it

shortly afterwards upon steamer-day.

There are numerous enfeebled, dispirited-looking passengers in the fore part of the vessel. These are the disappointed. They came to California, mistaking the country and miscalculating their own powers and the opposition before them. Perhaps they were without the physical qualifications for work, or some nicety of disposition or false pride prevented them from doing what their most successful neighbors had had to do at a pinch—turn their hand to any supposed mean occupation for a bare living. These sad and often seedy-looking mortals had, it might be, visited the mining country; they looked on for a time—wrought a day or two, perhaps only an hour, till their bones ached and their backs seemed breaking. Then they roared a curse against the mirage of gold, and set off to San Francisco. They had still a little money remaining of their first capital; but billiard rooms and bars, and the numerous other places for extracting cash from the idle and foolish, were rapidly reducing the amount. They made application for situations of different kinds, but they showed little energy even in that, and somehow they were unsuccessful. They had not the courage to offer to make, or to carry, bricks, or lime, to break up the French monopoly and blacken boots or hawk coals, keep a stall, slaughter a cow, or feed pigs, help to lighten a ship's hold, serve as waiter at an eating-house, or start into the interior and learn to plough, sow and reap, set and dig potatoes, or herd cattle. Some of these honest though supposed inferior occupations may always be depended upon by the truly industrious in San Francisco, while nobody need long remain in the despised situation, if his real abilities, energy and good conduct deserve promotion to a better. Our good-for-nothing fellows, however, would descend to nothing so "low." Low, indeed! as if they were the porcelain of the old world, and their nearest neighbors were only common delf. Well, time and their money were silently and rapidly disappearing. At last, a more vigorous effort than usual made them resolve to "shake the dust from their feet," and go home, with the faintest possible hope of having the "fatted calf" slain on their reappearance there. Importunities had probably coaxed or forced a few dollars from an old friend who was "doing well" in San Francisco, and these, with the scanty sum left of their own means, just paid up the reduced amount of passage money. Such unfortunates carry away a poor impression of the country; but their spiteful tales serve only to make themselves ridiculous among those who know the miserable character of the teller.

The thriving artisan who is paid so liberally for his services, and all other classes in turn occasionally visit "the States." Health or business, pleasure or personal duty and love to the dear absent, lead most of the more respectable people to leave the city for a few months, once in every two years, or so. There is likewise always a moderate number of officials, either of the city or State, or of the general government, who must occasionally pay a visit to the eastern capitals. Then sometimes comedians and other public performers, "stars" in their way, and a few "swells" and sharpers of the "Sydney-cove" school, a company of Uncle Sam's soldiers, a clique of filibustering speculators, bound ultimately for God knows what unprotected country, and many other curious characters book themselves for berths. A continued migration, backwards and forwards, is taking place. Of all those leaving probably one-third are sure to return within a few months. The voyage is long and inconvenient, with its own dangers too; but the voyager and the friends he is about to leave do not imagine that their separation will be eternal. There are only some contingencies in the way which tend to give their parting the slightest dash of melancholy. This, however, is usually mixed and disguised by a deal of gleesome envy and banter on the part of him that stays, and much eager, joyous hope in him that goes. Generally there am a few ladies among the passengers, though they are nearly lost to sight among the dark crowd of the "lords of creation." The female passengers have commonly a few friends of their own sex who sometimes attend and see them fairly off.

A considerable number of the passengers are foreigners; and while most of these first visit the Eastern States, they intend to travel much farther. In New York and the Atlantic ports, they will find abundant and cheap opportunities of reaching their "Beautiful France," or "Dear Father-land," or "Old England." They generally bear away a fair share of the golden spoil, and it is doubtful whether many of them will ever return. Boon companions and tried old mates of their own country witness their departure, and cheerfully congratulate them on the prospect of being soon again in a peaceful, happy home with "the old familiar faces."

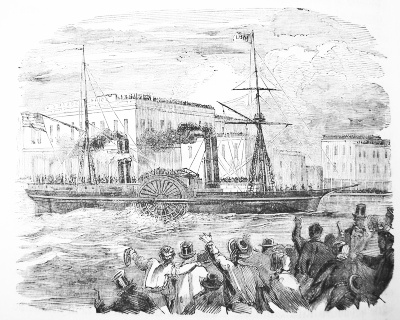

But leviathan begins to blow and heave uneasily, eager to be off. The escape steam-pipe seems too narrow a throat for the angry breath of the monster, and loudly threatens to burst, and the mighty hulk quivers at the sound. The clamor strengthens on deck. The mate begins to move about and shout, and the men leap to obey his orders. The chief engineer and his aids are at their posts, awaiting the word of command from the captain, who at last condescends to enter on the scene of action. A rapid shuffling of feet is heard, baggage is unceremoniously tumbled aside, sailors handle the hawsers, and laggers rush hastily to the wharf. The last drop has been drank, the last good-bye given. The wharf is densely crowded with spectators, while the voyagers every where occupy the different decks of the magnificent ship. There are a few turns ahead of the paddle-wheels, and then a few turns astern; the creature is lazily stretching its gigantic limbs before it begins serious work. The cables are cast loose, and leviathan yawns, and slowly drags its ponderous length half round.

There is meanwhile a general stillness observed by the spectators both on board and on the wharf. Their kind wishes, remembrances, orders, farewells had all been given; and the heart was too full, or the eye too busily engaged with the ever attractive scene, to permit further active demonstrations. Only a few unsentimental wretches will persist in bawling an untimeous coarse witticism, and shout still more "God-bless-ye-s" between the ship and the wharf. Perhaps a passenger, already "half seas over," in the delirium of his joy and drink, will toss his hat to a friend whom he is sorrowfully leaving, as a token of his last affection; or the deserted crony will throw his own "tile" towards the "bosom friend" of many tipsy hours. Three to one, these last fond memorials drop short into the water. Sometimes quite a brisk fire will be thus kept up for a quarter of an hour, while the ship is getting under way; and oranges, hats, sometimes coats even, last notes and packets, jokes and repartees, will fly from man to man across the widening space that separates the parties. Such noisy salutations and gifts, however, are in the end confined to a few. During the last ten minutes the passengers are forming into a close line, and lean across the rails.

Occasionally they appear to whisper to each other about the incidents passing a few yards off. Now one and then another, bows to some friend in the crowd, whose eye he could not resist catching once again, while a faint, half joyous, half melancholy smile plays upon his face. The friend answers the familiar nod, and seeks to avoid meeting any more the gaze of the departing.

Slowly and heavily, leviathan plashes and plunges; it moves round the outer end of the pier till its head is clear of the farther wharf. Then the great heart ceases for a moment to beat, mustering its energies for the coming race. The excitement among all increases. Now the ponderous iron beams lazily rise and fall. For a moment there is no perceptible motion of the ship. The excitement is intense. Then one sharp eye, and next another, discovers and proclaims loudly that the large bulk is really moving. Onward—slowly, slowly—a little faster, though still but slowly—then moderately—a little more quickly—then faster, proudly, triumphantly, with a continually accelerating speed! Oh, it is a beautiful, a grand sight, such a majestic vessel exerting its enormous power, and growing momently in strength and swiftness! So soon as the ship is seen to be really moving ahead the interest of the spectators is at the height. Hats, caps, handkerchiefs, hands, are eagerly waved, and a multitude of cheerful voices bid a long farewell. The travellers gaily show like demonstrations of interest and friendship. A few tears moisten the eyes of the more sensitive. With one general impulse, three hearty cheers are given by the forsaken, which the departing as heartily return. As the loud huzzas die away, and the sullen crash of the paddles is beginning to be distinguished, smoke is observed near the bow of the ship, and at almost the same instant the boom of a cannon-shot is heard, which thunders and re-thunders among the cliffs of Clark's Point—and the steamer has fairly started. For a few minutes afterwards the eager crowds can mark the tall masts and the fluttering pennant, till the ship gradually bends oceanward, and Telegraph Hill hides her farther progress through the Golden Gate. Then with a long-drawn breath—genuine sigh, or a laugh, the multitude bustle and hurry off to their proper kinds of business, to forget all about the event and their emotions, until some subsequent steamer-day recalls these to mind, by circumstances of a similar nature.

The arrival of the steamer bearing the eastern mails is likewise an occasion of much excitement—not so much in respect of there being possibly some six or eight hundred passengers on board, as because there are fifty thousand letters and newspapers coming from home. The telegraph has some hours before announced that the "Golden Gate" is approaching the Heads. The glad tidings soon spread through the town. Those who expect to find friends hasten to spy and welcome them before even the vessel touches the wharf. Draymen and cabmen speed with their wagons and coaches to secure a job. A multitude of persons attend for the novelty and excitement of the scene. There are nearly as many persons on the broad wharf as on the occasion of the steamer departing. On sweeps the "Golden Gate"—a magnificent specimen of the first-class ocean steamer. Her decks are crowded with human beings. Dense masses cluster on the highest plank that can afford them footing, and cling high to the rails and rigging. The passengers are chiefly fresh immigrants, who have sought the land of gold and marvels, to make or recover a fortune. And this is San Francisco! they say to each other, as they mark the forest of masts, and the hill-sides covered with buildings. Well! it exceeds all my expectations! But we have not space, Asmodeus-like, to uncover the chambers of their brain, and tell the various thoughts, fancies, hopes, ambitions, of the sanguine immigrants. Among them are those who must and shall succed, and also those who will sorely be disappointed and lamentably fail. Among the last are a large proportion of medical men, political place-hunters, lawyers, and such as would fain live more by their wits than by rude manual labor. The most of these men—many of whom are highly educated in classic and polite literature,—must forget their refined associations, and submit to corporeal drudgery, if they would thrive in San Francisco. If they cheerfully do that, there is hope and furtune in store for them.

For a few days such as intend to betake themselves to gold-digging remain in town, and with staring, greedy eyes, look about them, while they recruit their strength. Thus many a lank, awkward, budding Hercules may often be seen dreamily wondering, while he wanders through the streets. Or if there be good demand for laborers in San Francisco, some may take a few weeks spell at town work, to earn a "slug" or two, to help them to travel farther. The finances of the newly-come immigrant are commonly but scanty. Many skilled mechanics and tradesmen are among the number; and these generally find instant employment, if they diligently seek it, in their various occupations. If the particular kind of business, however, which they wish, and are best fitted for, cannot be obtained, then, as they have hands, and eyes, and feet, and may have willing spirits not above coarse work, they may always find something to do, to keep soul and body together and save a little money to wait till their better time comes, when they may have a choice of employment. But gradually many of the fresh immigrants swarm off to Sacramento, and others to Stockton, as the first stages to the mining regions. A considerable number of the passengers, particularly those in the cabin, are only returned Californians, such as had gone off some months before. These are gladly coming back to speculations and hard work, to feverish passion, wild delights and all the dear, wicked, fast life of San Francisco. The austerities of New England, the dull proprieties of the Quaker City, and the general monotony of society over most parts of the East, have only sharpened the appetites of the old settlers for the delightful excitement that ever reigns in the noble city which they themselves have helped to create.

The expresses hurry off their packages, mails are landed, decks are

cleared, and the passengers have all found a temporary lodging. The post-office

establishment is meanwhile as busy as possible, arranging the letters for

delivery. Merchants open their private boxes and find the all-important

missives they looked for. Anxious crowds gather at the windows and with

beating hearts ask for the longed-for, half-expected letters. The reader

may readily imagine their mingled hopes and fears as the clerk answers

their inquiries. He who is blessed with news from home tremblingly unfolds

the precious epistle in the street, and devours, as it were, with gloating

eyes, the suhstantial words. The disappointed seeker turns ruefully away,

to hope for success next mail.