Noe Valley Land Suit

Noe Valley Land Suit

A

suit involving $24,000,000 worth of property is soon to be brought by the

heirs of Jose de Jesus against the owners of land, improved and unimproved,

and of divers houses and lots, in that portion of the City known and designated

on the maps as San Miguel Rancho.

A

suit involving $24,000,000 worth of property is soon to be brought by the

heirs of Jose de Jesus against the owners of land, improved and unimproved,

and of divers houses and lots, in that portion of the City known and designated

on the maps as San Miguel Rancho.

The complaint is now in process of compilation and copies thereof will be served on upward of 7000 defendants, including the City and County of San Francisco, the Southern Pacific Railway Company, the Stanford estate, Crocker estate, Adolph Sutro and all of the land companies that have been organized to buy and sell land in that district.

All the land comprising the San Miguel Rancho was acquired from the Governor of Alta California in 1845. Noe transferred it to W.J. Horner. The heirs claim that Senor Noe had no right under the Spanish law to make said transfer, and thereby hangs the tale. The family of Noe ranks among the oldest Spanish families in the country, and the litigation will carry with it an interest second to that of no other civil procedure now on the records of the courts.

Messrs. Gunn & Koscialowski, attorneys for plaintiffs, stated yesterday that the suit was based on the petition of Jose de Jesus Noe to the Governor of Alta California dated May 18, 1845, in which the petitioner asks that the Governor grant him one square league of land lying west of northwest of the Mission Dolores, bordering the ranches of citizens Francisco de Haro, Robert Riddle and Jose C. Bernal, agreeable to the plat which accompanied his memorial, and bounded on the west by the ocean. It was set forth by the petitioner that he had a large number of cattle and horses whose increase had been such that his prior holding was insufficient for their feed and pasturage, and further, that the petitioner's family would receive the benefit of such grant from his excellency.

The grant was made and the Noe cattle and horses browsed over the land which was thereafterward known as the San Maguel [sic] Rancho.

In 1848 Mrs. Noe died, leaving three sons. Five years later, in 1853, Jose de Jesus Noe conveyed the rancho to William J. Horner. The heirs now contend that the conveyance was illegal. Their names are Miguel Noe, Vincente Noe and Catalina Noe. Miguel Noe is the son of Jose de Jesus Noe and the others are his grandchildren.

"Why was the transfer from Noe to Horner illegal and why has it rested so long without an attempt being made to set aside the conveyance?" was asked.

"The question is a natural one," admitted Mr. Koscialowski, "but I think it can be answered clearly. It was illegal for the reason at the time Mrs. Noe died, under the Spanish law as it then existed the property vested in her children, and the husband had nothing more than a usufructuary interest during the minority of the children. The reason why action was not taken before is because the decisions of the courts of California have held a different view. The reason why action is taken at this time is because within the last three months it has been discovered that the courts erred as to matters of fact, that is to say they had made a mistake as to what was or what was not foreign law when Calfornia was under Mexican law. The courts in California in their construction of Mexican land grants made of property in this State prior to its admittance to the Union have almost universally held that such grants should be classified 'Bienes Ganaciales' (donations) made by the Government."

The case of Panaud vs. Jones, 448 First California, was referred to by Mr. Koscialowskl [sic], in connection with others of record, as showing, according to his interpretation and that of prominent Mexican attorneys, that under such grants as the one in question the husband has no right to transfer property after the wife's death; that it vests in the children, and cannot be disposed of until the children are of age. In the case of Panaud vs. Jones the grant was made as a reward for military services. In the case soon to be at bar the land was given for agricultural purposes, the benefits to be shared in by members of the grantee's family.

"We claim," continued the attorney, "that Noe senior had no right to make the deed he did to W.J. Horner, and that the present owners of the land bought it at their own risk without sufficient investigation as to the title on the principle of caveat emptor (purchasers beware).

The attorneys for the plaintiffs claim to have made a thorough research among the earliest Spanish records, and they have had translators at work for weeks here and in Mexico on the laws in force at the time California was under Mexican rule.

According to the Escriches, a ponderous Spanish law tome, the act relating to the husband's and wife's interest in grants similar to the one in question has been in force 300 years, and is operative to a great extent today in the settlement of estates in Mexico, Spain and even in France. In the suit to follow Spanish law will be quoted in extenso.

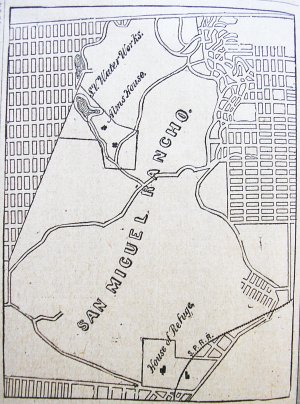

The property involved in the suit is roughly estimated to be worth about $24,000,000, and includes the whole of the original San Miguel Rancho. More accurately described, as is shown in the accompanying map, the boundary line extends from the junction of Valencia and Nineteenth streets along the line of the old San Jose raod as far south as the county line, thence to a point near the Haight-street ball grounds and back to Nineteenth and Valencia, including the Almshouse tract, House of Refuge, Spring Valley Water Works Company's property near the Almshouse, all of Horner's Addition, Lake Fremont Land Association, Railroad Homestead, Park Lane tract, Clarendon Heights, Market-street Homestead, San Belle Rocho tract, San Miguel Homestead Association, and all the Mission blocks from 71 to 114, inclusive.

Papers will be filed in a few days.

Source: The San Francisco Call, 13 August 1895, page 8.

The pending suit of the Noe heirs against the property-owners in that part of the city known as the San Miguel Rancho, an account of which was published exclusively in THE CALL yesterday morning, created an interest among the dwellers of the district in proportion to the enormity of the land values involved.

Careful and conservative estiamtes do not decrease the probable amount of the property values as first given—$24,000,000—and some place it even higher. In all such suits there is a disposition to consider the action in the manner of a "bluff" for ulterior purposes, but in this instance the long residence and social standing of the plaintiffs in this City is calculated to render any such deduction or surmise inappropriate.

The Noe heirs have employed prominent and responsible Mexican consul, in connection with Messr. Gunn & Koscialowski, to prosecute a thorough research into the fundamental Spanish laws in operation at the time the Governor of Alta California made the grant of one square league of land to Jose de Jesus Noe. All the early land transactions were made under these laws, and the oepration thereof has furnished the basis of innumerable suits to satisfy title since the State was admitted ot the Union.

The attorneys for the plaintiffs call attention to the fact that the California courts have been at varience in their interpretation of the Spanish laws for years past, and that no ultimatum has ever been established. This may also furnish an explanation for the disinclination of other attorneys likely to be interested in the big suit on behalf of the 7000 or more defendants to express an opinion concerning the extent to which land grant transactions are amendable to the Spanish law. Whatever the cause, those who were asked for an opinion yesterday declined to express themselves on the ground that they had not had time to look up the law.

Mr. Koscialowski said:

There is nothing but law in the suit, and the heirs are too well known to permit of the slightest suspicion of a money extortion scheme. The courts of California have held almost universally in their construction fo the Mexican law that all land grants made prior to the admission of California into the Union should be classified as "bienes gananciales" (donations) made by the Government. In the case of Panaud vs. Jones, First Cal. 448, the court, after reviewing the case at considerable length, decided that the property received by Alviso, by way of grant was ganaciales (gains), and asserts that Alviso had entire control and right to dispose of the whole gananciales. Mrs. Alviso died before her husband, but the court held that no estate vested in the children, and that it was common property on the decease of their mother, and that their title interest only became perfect after the death of their father, and only then after the debts had been paid. Now, by Escriche's (Spanish lawbook) definition of gananciales, it is shown that property received by the grantee as a reward for military services was his separate property, for at the time he was performed these services he received a salary and support from the vices he received a salary and support from the Government. But if, at the time of performing these services, he was paying his own expenses, living on the income derived from the "dotal" property of the marriage, then such grant should be gananciales. Alviso received this grant in return for military services, and it is not known whether he lived upon the salary received from the Government during the performance of these services, or whether he paid his own expenses out of the gains and profits. I call attention to this for the reason that Escriche says that the wife had tacit mortgage on the separate proeprty of the husband to compel said husband to make good to her or her heirs the dotal property he might have received either before or after marriage. Now, this grant received by Alviso for military services may have been his separate property, in which case his heirs would have a claim upon it, but not through their mother's mortgage upon the same as described above.

Many of those connected with the land and improvement companies operating in the district have Government patent titles to the land, and laugh at the idea of such a preposterous claim being set up at this time.

Source: San Francisco Call, 14 August 1895, page 8.

Judge Sanderson Decides Against the Noe Claimants.

He Holds That the Position Taken by Them is Altogether Untenable.

They Have No Lawful Claim to the Four Thousand Acres of Land in Dispute.

An Appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Attorney for the Heirs of the Noe Estate Thinks That the Court

Misinterpreted the Law.

Judge Sanderson rendered judgment yesterday in favor of the defendants in the suit brought by Miguel Noe, Vincent Noe, Catalina Noe and Catalina Splivalo to quiet title to a one-half interest in over four thousand acres of land, known in the early history of the city as the "San Miguel Rancho," but now more popularly known as the "Mission." The title to the land was claimed by the plaintiffs as the heirs of Guadaloupe G. Noe, wife of Jose de Jesus Noe, to whom the property involved was granted by the Mexican Government in 1846, through the agency of Pio Pico, the last of the Mexican Governors of this State. After California became a State the land was patented to Noe by the United State Government. In 1854 the property was conveyed by Noe to John Horner.

Judge Sanderson in reviewing the case says in substance:

Senora Noe died April 15, 1848, and the claim of plaintiffs is based upon the theory—first, that the land in question being not a donation or gift to the husband, but a purchase by him from the Government of Mexico, by virtue of this Mexican or Spanish grant; therefore, the land in question became and continued community property of the spouse, one-half of which passed to the heirs of the wife at her death, under the Mexican law in force at her death; second, if the property be such gift or donation, then that the law in existence at the time it was made controls and vests the title to the heirs of Senora Noe. It being plaintiffs' contention that Noe, the husband could, in law, only convey a valid title to an undivided one-half, at most, of the property to Horner, though the deed purported to convey the whole, and that the title to the remaining one-half is still vested in the heirs of the wife. The plaintiffs claim title, it will be observed, through the wife and not in any manner through the husband. Noe made no transfer in his lifetime to his wife; he died long subsequent to her death, and she therefore, could have received no claim to the property as his successor in interest. The only questions, therefore, to be decided are: Was this land the common property of Noe and wife, or, if not, then was the property of such peculiar nature as prevented the husband from disposing of the same? The defendants claim it was not common property, but ever was the separate property of the husband, free and clear from all claims of the wife and her heirs, and that he had a perfect legal right to dispose of the entire property to Horner in the manner shown.

Turning now to the question of the character of the property which passed

by reason of this Mexican grant it becomes apparent from what has already

been said that if this grant vested the title absolutely in the husband

as his separate property, and to the complete exclusion of his wife, then

the plaintiffs have not a valid cause of action against those defendants,

because they will then have failed to show any title whatsoever in themselves.

This grant to Noe was made by Governor Pio Pco under the Mexican colonization

laws of 1824 and the regulations of 1828, and is what is known as a "colonizing

grant."

These grants were made upon petition. Noe's petition recited that he had a numerous family who would receive the benefit of the grant. The grant issued to Noe is in his own name, but it may be assumed, or conceded, that he received it as the "head of the family."

This grant was made to Noe "on conditions," so to speak, that is to say, he was, on his part, to perform certain acts and refrain from others, the "conditions" being (1) that in fencing he should not disturb existing servitudes and (2) that he should solicit judicial possession. The land granted, likewise, was to be used as a cattle range. The grant being of one range of greater cattle. The grantee, however, was note required to pay any consideration therefor, nor was he obligated to fence, build, cultivate or reside upon the land.

In 1859 the supreme court had occasion, I believe, to first pass directly upon this matter and the nature of these colonization grants in Scott vs. Ward, 13 Cal., 459, although in the estate of Buchanan, 8 Cal., 507 (affirmed in Scott vs. Ward, supra), the law of Mexico with respect to the property of husband and wife was discussed and declared to be the same in effect there as here so far as it related to the merits of the question before the Court. In the Buchanan case, however, the land in question was acquired by purchase, and not by gift, and was therefore common property.

It is contended by plaintiffs that the grant in the case at bar can, and should, be distinguished from teh case of Scott vs. Ward, because it appears that Alviso, the grantee in that case was a retired Sergeant, and therefore the grant was, or may have been, for military services, and thereby became a grant, on consideration, and not a donation or gift. It is true that the Rev. Father Minister of the Mission of Santa Clara, in his report commending the application of Alviso to the favor of Governor Alvarado, states this fact and says Alviso is deserving "of any favor" for that reason, and also because he has a family and numerous cattle; but there is nothing to show that the grant in Scott vs. Ward was made because of Alviso's military services. He would undoubtedly have received it had he never performed sch services, and that fact is not even noticed in the Court, and, apparently, was not worthy of notice for the attorney in that case; William Mathews, placed no reliance thereon. The opinions in Scott vs. Ward were both delivered by Justice Field, all of the Associate Justices concurring. In my opinion this case decides the particular point in issue here, and it has been followed and repeatedly confirmed from the day it was decided down to the present time without a dissenting voice from any Court, so far as I am advised.

In that case the Court held that the colonization grant there under discussion vested a separate estate in the husband freed from any and all claims of the wife or her heirs, the language of teh Court, in that behalf, being as follows: "We are of opinion that the grant in question was a simple donation, and that the land it contained constituted the separate property of Alviso and passed under his last will and testament."

After reviewing several other cases, in which the same ruling was upheld, Judge Sanderson says:

The case of Berryessa vs. Schultz, 21 Cal., 513, arose, also, over one of these colonization grants like the one at bar. This grant, also, recited that the same was made for the "benefit" of the two brothers Berryessa, and "that of their families, their parents and brothers" and required them to build a house thereon within one year, which should be inhabited. Of this grant and recitals, the court said, "the position of the appellants is that this grant was inteded not merely for the benefit of the (two brothers Berryessa) grantees named therein, but also for the benefit in equal shares of all the members of the Berryessa family—the fathers, brothers, and children of the grantees."

The court held this position untenable, saying the grant vested the grantees therein named (and those alone) with the full and complete title to the land granted. The court in deciding the case adopted the language of another case (Frigue vs. Hopkins, 4 Martin, N. S. 214), saying: "By the regulations of the Spanish Government, if the individual who applied for land was unmarried, a certain quantity of land was given to him; if he had a wife, this quantity was increased, and if he had children an additional number of acres was conceded. Now, if the circumstance of this being married made the thing given become the property of both the husband and wife, we must, on the same principle, hold that where children were the moving cause, they too shouldbe considered as owners in common of the land conceded. But that such was the effect of the donee having a family, we believe was never even suspected, it certainly is unsupported by law."

I shall cite but one other case to sustain the proposition of law upheld in the foregoing authorities, viz.: Hood vs. Hamilton, 33 Cal., 698. The opinion in that case was rendered by Mr. Justic Sanderson, nearly thirty years ago, in the course of which he says, "We are of the opinion that Scott vs. Ward does determine that land granted under the colonization laws of Mexico to married men, become their separate proeprty and not the common property of themselves and their wives. Whether the grant there, before the court, was a colonization grant or not, it was so regarded by counsel and court. It was the law of those grants which was debated by counsel and declared by the court, and whether the correct result was reached or not, we do not feel at liberty to disturb it. Being of this opinion a rediscussion of the question would be idle and out of place. The rule in Scott vs. Ward has been repeated in Noe vs. Card, 14 Cal. 576; Fuller vs. Ferguson, 26 Cal., 546, and Wilso vs. Castro, 31 Cal., 438, and must now be accepted as a finality."

From the time of that decision to the present, it has never been disturbed. It woudl seem idle and superfluous for me to say more, to to devote more time to the discussion of this topic; indeed, it may well be said, that it seems like time and labor lost to have devoted so much of either to a rehearsal of these old and fundamental cases, whereby the contention of plaintiffs is shown not alone to find no support, but is thereby affirmatively and effectually demolished.

The industry of counsel for plaintiffs in presenting this case for his clients, and his apparent earnestness in contending that the case at bar could and should be distinguished from those heretofore cited and decided by our court of last resort, and led me to perform the labor in carefully examining those cases when comparing them with the case at bar.

I trust, and believe, I have clearly shown that a Mexican grant of pueblo or rancho property in California made to a married man for the benefit of himself an dfamily, upon conditinos such as those contained in the grant in question, vest the title absolutely in the husband as his separate property and estate, free and clear from any claim on the part fo the wife or her heirs.

The main point relied on by plaintiffs is wholly without merit, and the bringing of this suit based ont hat contention has been far worse than useless, for it has entailed much epense on litigants without establishing or reasonable hope of establishing any new rule of decision as to these grants.

Titles to proeprty, from one end of this State to the other, rest and are dependent upon the rule and decisions heretofore noted.

The land in question here was given outright by the Mexican Government to Noe in 1846. He paid nothing whatever for it, and some eight years later he sold it to Horner for $70,000, it appears, and now, a half a century later, the proeprty, largely covered by improvements, is said by counsel to be worth upwards of $50,000,000. Upon it are found the homes and probably the entire fortunes of thousands of inhabitants of this city, who have lived there in perfect legal security as to their titles, which have been unquestioned for nearly if not thirty years last past. At this late day an assault on this character upon these titles, based on a question and contention of law long since definitively fixed and settled by our courts, must strike the ordinary mind as wholly without justification, and prompt the wish and show the necessity for some remedy at the hands of our legislators whereby long-established owners of property, such as the numerous defendants in this action, may, if possible, be protected to some manner from bringing of suits like the present one against them to determine a question long since laid at rest, without being compelled to undergo the expense and annoyance of defending an unfounded action in order to keep their titles uclouded [sic]. There is no way under the present law, so far as I am advised, by which the good faith of the plaintiffs in such suits can be tested or guaranteed prior to trail, but this I believe can be effected by a proper law in that behalf. The necessity of such a remendy could not easily be more forcibly illustrated, in any opinion, than by the present suit.

The counsel for plaintiffs contends and seeks to show that if the proeprty conveyed by the Mexican Government ot Noe by virtue of the grant was a gift or donation, then that such gift or donation was "subject to the laws in existence at the time it was made, by which title to such gift or donation was controlled," and proceeds therefrom to apply the Spanish law of "dote" to such gift or donation. Primarily this law of "dote" signifies somethign given to the wife or to some one for her benefit; in other words, it is a marriage portion to the wife. The husband controls the "dote" during marriage, but on the dissolution of the marriage the entire "dote" returns to the wife, or her heirs. From what has already been said it is plainly apparent that this law of "dote" has no applicaiton whatever to the gift or donation comprised in this Mexican grant of land given to Noe, the husband. It was in no sense a marriage portion of the wife and never inteded to be, but simply a figt and grant of land to the husband. For the "benefit of his family" it is true, are the words found in the grant itself, but all of the cases cited expressly declare that those words of rectial innow way control the characer of the land granted; that in such grants the title invested exclusively in the grantee therein named, and that the same thereby becomes his separate rpoperty and estate freed from all claims on the part of the wife and her heirs, which might otherwise attach were it common property inestead of the separate estate of the husband, as the decisions quoted clearly and decisively declare it to be. Let judgment be entered for the defendants.

Among the property-owners in the Mission who are directly interested in the decision are:

Sigmund Augustein, Wellington C. Burnett, N. J. Benson, Richard Bullock, Maria Brandt, William C. Bush, O. D. Baldwin, Sarah J. Boyle, Arthur C. Burke, William E. Boyer, Charles C. Blakly, George J. Becht, Edwin D. Bennett, G. H. C. Beckerdorff, Edwin Barnett, May Chambers, Charles W. Chapman, Hugh Curran, Israel Cohen, William A. Caldwell, Thomas Breagmile, Morris A. Cohl, C. W. Courtridge, Annie Doyen, Mary Dunn, P. J. Dufficy, Daniel Donovan, Gus W. Dorn, Amand Durat, John Duffy, H. M. G. Dahier, Isaac Eliaser, Mendel Esberg, James L. Fraser, E. F. Freeman, Joseph Flach, James Feifelberg, Annie Grimpel, Michael C. Gorham, Eugene J. Goss, Golden Gate Park Land and Improvement Company, Carl Griese, Amelie Griese, John J. Galvin, Mathilda Holling, Milo Hoadley, Henry T. Holmes, Laura T. Holmes, Carrie Hund, B. W. Haines, R. P. Hammond, Mary Hoesch, Henry L. Johnson, Adele S. Jardine, Thomas Kelly, Homer S. King, Clement Kormil, Mark Levi, Mary T. Lawless, H. Laufranchi, Patrick Lyons, Charles Lionhardt Jr., Ida L. Lovelace, Prudence M. Luckey, John McLaren, Emma Meyer, Carl A. Muller, Market and Stanyan Street Land and Improvement Company, Emanuelitt McKentry, Johannes Moller, Henry Mauser, William W. Moore, Julia P. Magill, Ida Mentz, Edward E. Manseau, George L. Munro, James J. Macdonald, Robert McMillan, Jorgen Neilsen, Helen G. Noonan, Dennis Noonan, Julius Newman, Carl E. Olsen, Mary Post, George H. Porter, Henry Pilster, Bridget Philbon, John H. Pauls, Joseph Prosek, T. P. H. Penprase, Susie Roche, Frederick Rothchild, Henry Rothchild, Alex Rothenstein, John Rogowski, Edgar Strauss, Catherine Schieffer, Rebecca Silverstein, Michael J. Sawyer, Kate Steinmetz, Albert Schohay, Mary B. Stoner, N. Schlessinger, Samuel M. Thompson, Eliza Taylor, Mary J. Turner, Charles Warren, W. B. Walkup, Albert Waldier, John J. Walkington, Elsie A. Mayden, Castro Street Land Company, Jacob Heyman, Solomon Getz, C. G. Kenyon, John Caine, M. A. Austin, D. H. Austin, D. H. Burnham, Julius Bernoulli, Otto Blankart, J. Buck, William H. Chapman, M. W. Connor, Clarence De Vincent, Amelia S. Damon, Adolph Keller, Lewis J. Laplace, John J. Meyers, N. Ohlandte, Henry Ohlandt, Jean E. Rutherford, John R. Spring, William M. Fitzhugh, Forrest S. Rowley, Otto Jungblut, George O'Byrne, Joseph I. Lawless, John H. Rosseter, J. A. Miller, Elsie T. Niles, Frank A. Geier, John Van Tassell, Margaret Mayo, J. B. Lee, H. Lacy, Herbert E. Chesebro, W. H. Stanley, Thomas H. Betchell, Lillie Conklin, Robert H. Blanditig, Julius Blumenthal, Mary H. Jewett, L. H. Bonestell, Annie T. Dunphy, John Morgan, William Rickerby, M. Burns, H. Holman, Behrend Joost, John Pfor, Home of Peace Cemetery, Congregation Shereth Israel, John H. North, D. W. Gram, William Kelso, A. G. Forsberg, Peter H. Olson, J. H. Cattran, Charles Hellman, John J. Johnson, Thomas E. Ryan, William H. Miller, Henry G. Swan, J. W. Smith, James S. Campbell, [undecipherable] Miller, John H. O'Connell, Peter Kelly, Thomas R. Dunn, D. A. Curtin, William Doran, William W. Rednall, John H. Kusel, L. H. Wainwright, H. S. Greeley, J. M. Cox, Charles Lester, J. C. Holoway, George P. Dorgan, Margaret A. Skelley, William Patterson, Charles S. Marney, James Connell, A. Hattabough, L. G. Williams, M. A. Cachot, Fred C. Siebe, Jacob P. Selmer, William J. Welch, Sarah A. Madden, George Marzolf, M. Simpson, George C. Smart, Charles Nopper, J. W. Carr, Patrick Tiernan, J. Lynch, Samuel J. Marshall, John Harrigan, C. L. Tilden, Stanley Coghill, Charles M. Wiggins, James Keene, J. A. Cooper, M. L. Kelly, W. B. Swain, Alexander F. Homberg, H. Wilder, William Drury, Thomas J. Crowley, C. C. Darling, J. G. Klumke, L. E. Osgood, Patrick Cosgrove, J. C. Carroll, F. G. Brooks, Robert Benson, A. F. Caseboldt, Henry J. Foley, Richard H. Harris, Hugh B. Jones, James Moore, Henry Lamp Jr., Charles A. Pless, Max Popper, Arch. B. Thompson, Samuel Wyatt, Emma E. Chapin, William G. Barlow, James McMichael, B. A. Peckham, Joseph Sicke.

There are two other suits brought by the same plaintiffs involving the titles to property owned by about 4,000 defendants pending in court. It is believed, however, that they will be held in abeyance until the case decided by Judge Sanderson yesterday has been carried to a higher tribunal.

Attorney P. L. Koscialowski, who represents the plaintiffs in the action, intends carrying the case to the Supreme Court of the United States if the decision of Judge Sanderson is upheld by the Supreme Court of the State.

"It is very clear to my mind," said Koscialowski yesterday afternoon, "that Judge Sanderson does not yet fully comprehend the points in this case, notwithstanding the careful and earnest effort made to clearly set out the law and the facts. For instance, the honorable Court seems to have received the impression that the plaintiffs have endeavored to establish 'a new rule of decision as to the grants,' wherein plaintiffs have emphatically stated and shown that never has there been any rule adopted to control the title to such grants, standing in the peculiar position the plaintiffs do to the occupants of their lands, and consequently they regret that there is no method by which their good faith might be tested. I can assure the good people who live on the property in question that we are perfectly satisfied and firm in our belief that we are in the right, and expect to fight for the recovery of our rights in sincere earnest.

"The Court seems to have overlooked the fact that the question is whether or no [sic] under the law in force in 1853—not the law of to-day—Mr. Noe could dispose of the entire community property while the children of the marriage were minors.

"How the Court could come to the conclusion that when community property was sold it is presumed to have been sold for the payment of debts is beyond my comprehension unless it be in an effort to establish 'a new rule of decision as to these grants.'

"When it comes to the question fo the law of 'dote,' the translation of the Spanish law submitted to the honorable Court clearly reveals that fact that any stranger, even after twenty years of marriage, could give the husband property for the benefit of his family, and the property would belong exclusively to the heirs of the wife after her death. I have studied these questions closely and carefully during the past eighteen months and am perfectly satisfied that our position is the correct one, and that there are no decisions in the California Reports which cause me to think otherwise. Believing as I do that I am in the right and that the rights of property were vested in Mrs. Noe's children before the ratification of the treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo, and that said treaty guaranteed them protection and which is part of the supreme law of the nation and that no State law can override, I would be unfaithful to the trust reposed in me by my clients had I not entered into the suit with a full determination to fight for their rights to the highest court in the land. An appeal will at once be taken to the Supreme Court of this State, where the intricate points of the law in force here at the time of these transactions will again be reviewed and judgement asked for the plaintiffs.

"The question of 'dote' has never before been introduced in any of the cases touching title by Mexican grant, and if the Court has been asked to make an new rule at all, it is to make a rule in relation to this class of gifts. The Court admits that the grant was made for the benefit of Noe's family and holds that the said grant was a gift. It is therefore clear as the sun in the sky that such gift was made for the benefit of the family and therefore is a 'dote,' for that is exactly what is meant by the Spanish law of 'dote'; that is, a gift to the husband to maintain the family.

Source: San Francisco Examiner, 09 September 1896, page 9.

| Editor's note: If you are interested in early San Francisco property law and land titles, we highly recommend the following book: Colonial History of San Francisco, by Judge John W. Dwinelle, first published in 1867; also available in reprints. |