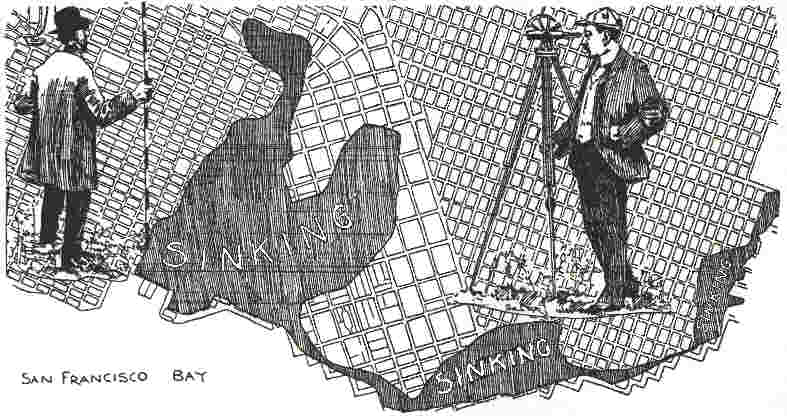

Sinking City

Sinking City

San

Francisco is sinking! This is the startling statement of the civil engineer

who conducts the work of the City and County Surveyor's office at the City

Hall. Sinking, slowly but steadily, each recurring year bringing additional

evidence that a large portion of the city would in a few decades be below

the waters of the bay.

San

Francisco is sinking! This is the startling statement of the civil engineer

who conducts the work of the City and County Surveyor's office at the City

Hall. Sinking, slowly but steadily, each recurring year bringing additional

evidence that a large portion of the city would in a few decades be below

the waters of the bay.

This is no wild or irresponsible statement, but a cold fact demonstrated and proved by the careful scientific observations of engineers in the service of the municipality, men who have been establishing levels throughout San Francisco for years, and have the data and records of the City Surveyor's office as the basis of their discovery. These engineers find in surveying, or leveling, in the unstable districts that the official monuments indicating the levels, or heights above the city base, have sunk with the land, and so it is necessary to being on firm ground and carry lines over those sunken marks, and always with the same result: streets, sidewalks, curbs, street railroads, buildings, all have gone downward together.

The peculiar nature of the sinking phenomenon is that the whole surface settles equally, a fact which has not only averted attention from the constant settlement, but also been the source of endless disputes between owners of land in the district, who imagine the grade is raised upon them by City Surveyors every few years. They say, "we are on the grade of the street, and now we are asked to spend money on raising the level." But they cannot realize that the new level, two feet or more above the street, is where that street was five or ten years before. The only remedy is to contribute to the cost of filling, raising buildings and building new sidewalks, an item of expense in connection with property now regarded in the settling places as something that cannot be avoided at least every ten years. Of course, since the settlement varies in different districts, the time for renewing the levels varies in length, as, for instance, on Market street, near the ferries depot. Fifteen years have elapsed since the land was raised to the official grade, and it is now being elevated to where it was then—just two feet in the air from the present street level, while on Sixth street, in the vicinity of Folsom and Harrison street, a raise was made in 1890, and now the land grade, as established and recorded at City Hall, is about sixteen or eighteen inches higher than the curbs. In other words, Sixth street in eight years has so far settled that its level in 1890 is an imaginary line in the air on a level with the knees of pedestrians now on that thoroughfare.

An interesting field for mathematical effort is opened through the City Surveyor’s figures upon this subject. The average sinking of those districts which insist on moving into nether regions, is two inches a year. There is a tendency to settle less as the years pass, though the settling does not stop, and the ratio of the decrease is so insignificant in comparison with the time as to be barely worth considering. Two inches may, therefore, be taken as the basis of calculating. In a hundred years the waters of the bay would be ebbing through the first stories of buildings, and the second floors would be what seamen call awash. Large vessels would find sufficient water in those streets to sail up to Sixth and Folsom streets and Market and California streets.

But as the inhabitants of San Francisco will keep on fixing the land, there will be no likelihood of such strange happenings as steamers coming up Sixth and Market streets. Earth will be piled upon earth until the sinking shall cease and then, in future ages, what a mine of vast geological significance will meet the eye of the traveler from Guam as he stands upon the ruins of San Francisco—a strange formation, indeed, with street upon street marking the strata two feet apart, and fragments of a past civilization in each, recording the fashions, characteristics and various brands of canned food of the early inhabitants.

The cause of this peculiar condition is a large area of the city is ascribed to the nature of the soil, which engineers describe a mixture of alluvium, washed down from the hillsides, ooze from the bay and decayed vegetable matter, the formation of ages upon the original bedrock. Formerly, before San Francisco encroached upon the bay, this area was partially covered with water, or consisted of swamp land bordering the bay. It was raised to the established official grades and soon covered with homes and business buildings, but the upper crust soon pressed down upon the ooze, and ever since more earth has to be added at repeated intervals to maintain the official levels. Engineers say that in places no bottom has been reached with piles sixty to eighty feet long, and the heavy structures erected thereon sustain the tremendous weight by force of friction, or resistance, against the sides of the piles. How deep is the ooze has not been ascertained in most places in the sinking area. Nor is it positively known whether the soft substratum moves on into the bay under the pressure, or merely packs firmer and so becomes more stable. When the Appraiser’s Building was erected long piles were driven to bedrock and it was found that the site was on the edge of the district. These piles indicated a sloping bedrock, the declivity being from Telegraph Hill southerly. After the massive building was finished, the Government engineers were astonished to find it moved in a southerly direction a few inches, the pile substructure sliding with it down the hillside.

One of the best authorities on the peculiarities of this area of uncertain soil is Edward J. Morser, the chief of the City Surveyor’s engineer staff. He has made a study of it in the last eight years during his connection with that office and watched each drop of the surface.

“In the last eight years,” said he, “this area has settled on an average of about two inches a year. This I have discovered by actual observations. On Sixth street in some places the settlement amounts to nearly double that, but the average in the district south of Market street is about two inches sinkage in the year.

“At the corner of Shipley and Sixth streets an exact measurement has been taken, and we found the settlement was more than two inches a year since 1890. Eight years ago it was found necessary to raise Sixth street from Folsom street to its southerly termination something like two feet to bring the street up to the official grade where it had been some years before. Quite recently a house was erected at Sixth and Shipley streets, and when the owner began to raise the sidewalk in front other property-owners protested against what they thought was raising the official grade. Then a careful examination was made and we found that the street had sunk just sixteen inches since 1890, and the new house was on the official grade, though sixteen inches higher than the present street level. At the corner of Sixth and Folsom it settles even more—fully three inches in a year; maybe three and a half inches. The land at that point is particularly unstable.

“The same thing applies to the district in that end of town, the settlement not being uniform, but varying in different places due, no doubt, to the character of the material used in filling and the difference in the consistence of the ooze underneath.

“A good illustration of the settlement toward the ferry depot is seen in the large buildings just finished or in course of construction between California and East streets, on Market street. They are on the official grade where the whole street was fifteen years ago, and the sinkage is indicated by the height of the new sidewalks in front of those buildings above the old levels—just two feet. Before long the whole street must be raised to the new level from which it has settled.

“When the Market-street Railway Company built its cable road to the ferries fifteen years ago the roadbed in the settling area was built upon piles and the line was laid on the official grade, to which the street was then raised. The raise was then about two feet. Now the roadbed has sunk with the street two feet from the official level, so that Market street has settled at least four feet to my knowledge.

“A house on piles doesn’t settle so much as other buildings; and still there is a slight tendency in them to settle. The piles hold merely by surface friction. Take Fair’s building at Washington and Drumm streets, in the settling district. It has settled about six inches in the past eight years, almost an inch a year and it was built upon piles.

“This settling had made much trouble in connection with the sewers, which in many places here broken, and sank below the outlets in the seawall. The settlement begins near First street and becomes more marked as you approach the easterly end of Market street. It will continue for years, but in time the tendency will be for the land to settle less than it has sunk in the past, or is now sinking.”