Norton I, Emperor of California

Norton I, Emperor of California

Norton

I, Emperor of California

Norton

I, Emperor of California

A Notable Chapter from the Story of Old San Francisco.

By James H. Wilkins.

NOTHING is sadder to contemplate than the mutability of human greatness. How many of those who climbed to a dizzy height in California's brief history have dropped from the pinnacle into the dismal company of "has beens"? How many of those who tested all the sweets of power, who were once admired, courted and envied are now as much forgotten as any of our arboreal ancestors? Governors, Senators, Mayors, Congressmen, leaders, bosses, agitators, fakers, have followed in orderly succession, as one wave succeeds another on the ocean, and have left no more trace on the mysterious sea of life. Only here and there some human islet rises among the waste of waters to remind us of the past. Just think a moment. Who was the lordly Mayor of San Francisco before the incumbency of James D. Phelan? Frankly, I don't know. Who was Governor of California before Hiram Johnson became executive? How many can tell that offhand, without consulting an authority? It is rather strange, then, that so many persons recollect that California once had an Emperor and retain a distinct impression of that august personality across a chasm of thirty-five years.

NOT all the pioneers of '49 were gold-seekers. Many were keen and experienced men of business and capital, who shrewdly surmised that the vast migration to the shores of the Pacific meant tremendous opportunities for trade. Among them was an English merchant of the old school who had been engaged in successful foreign commerce from youth to middle age. He settled in San Francisco in the days when the water came up to Montgomery street, and established one of the early commercial houses. Here again he prospered for a season. At the high tide of his fortune it is said he could have drawn his check for half a million dollars.

But in commerce in the early days was even more of a gamble than the games carried on at those-famous-haunts of Play, the Verandah and El Dorado. It was either enormous fortune or utter ruin. There was no world information concerning the immediate needs of the wonderful new commonwealth. In the absence of cables no accurate knowledge existed as to commercial movements. In each transaction every merchant took a gambler's chance. If a ship arrived with a cargo of goods in brisk demand the profits were enormous. But it often happened that one vessel after another sailed into port loaded with identical commodities for a market already glutted. As no sufficient warehouses existed the result was sometimes a total loss. They say that not a little of the "front" was filled with cargoes dumped overboard by luckless owners. A couple of disasters like this happened to the English merchant. He was just able to meet his obligations, like an honest man. But when the last check was drawn that squared his accounts his last dollar in the world disappeared.

There must have been a deep, agonizing mental pang, but it was mercifully brief. A cloud passed across his mind that blotted out every recollection of the past, and for, almost thirty years thereafter the old English merchant lived in a world of his own creation—the happiest man in San Francisco or anywhere else.

HIS name was Josiah Norton. When he came on the street after the financial clean-up no one could have been more serene, gracious and debonair. But about some very important matters his mind was a total blank and otherwise badly twisted. For one thing, he imagined himself the all-puissant ruler of the Pacific Coast. He scorned the imputation that he had ever been a merchant. What! He, Norton the First, Emperor of California and Protector of Mexico, degrade his order by mixing in the vulgar trade! He implored his faithful subjects not to connect him with such unworthy thoughts. And Emperor Norton I he remained until the unwelcome visitor, who spares no potentate, ended his long reign—1851 to 1879.

IN our time Emperor Norton would be locked up in a madhouse and the incident closed. But the old town, with all of its failings, had a fundamental goodness of heart, and, what was more to the point, an acute sense of humor, whereby the pleasure of existence is much enhanced. When the peculiar nature of Josiah Norton's affliction, or, rather, hallucination, became know to his numerous acquaintances they realized that the man was entirely harmless, both to himself and others, and they simply let nature take its course. But, in one way or another, provision was made for his support, which was well repaid. For instead of wearing himself out behind iron bars Emperor Norton became a part of San Francisco, a never-ending source of pleasantry and amusement—better known throughout the world than many of the genuine crowned heads.

IT was shortly after his assumption of imperial powers that his Majesty, Norton I, assumed the attire that never varied during his reign. This was of a fantastic military design, with pinchbeck decorations and surmounted by heavy epaulettes. The regular headgear was an ornamental soldier's cap, but, on state occasions, as better fitting his dignity, he substituted a high silk hat, with a bunch of feathers stuck in the front, usually the plumes of the turkey or domestic hen. These garments were constructed by a fastidious tailor, and were regularly renewed twice a year. A tale used to be current that an old friend went sponsor for the payment, but as various citizens were each named as the alleged benefactor it is safest to dismiss the story as a myth.

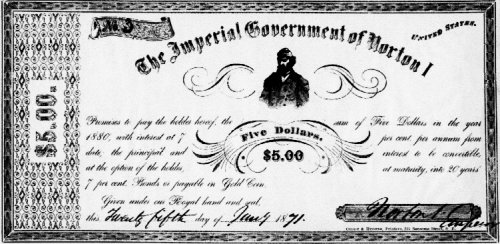

As

a mater of fact, His Majesty, was not without resources. Besides

promenading

Montgomery street of an afternoon, issuing printed proclamations

concerning

affairs of state and entering into elaborate correspondence with the

crowned

heads of Europe, Emperor Norton issued paper currency of his own, which

was always honored in certain quarters. The imperial obligations were

always

in [t]he sum of five dollars, and it was somewhat noteworthy that he never

presented more than one of these at a time to his "treasurer" in the

financial

district; and as these were very numerous in the old days he derived a

tidy income without imposing serious burdens on anyone. In fact, he said

it was the imperial pleasure to make taxation light. Therefore, there was

no need to conjure up an imaginary guarantor of his tailor bills. He lived

in good quarters, had three square meals a day and met his various small

accounts with unfailing regularity.

As

a mater of fact, His Majesty, was not without resources. Besides

promenading

Montgomery street of an afternoon, issuing printed proclamations

concerning

affairs of state and entering into elaborate correspondence with the

crowned

heads of Europe, Emperor Norton issued paper currency of his own, which

was always honored in certain quarters. The imperial obligations were

always

in [t]he sum of five dollars, and it was somewhat noteworthy that he never

presented more than one of these at a time to his "treasurer" in the

financial

district; and as these were very numerous in the old days he derived a

tidy income without imposing serious burdens on anyone. In fact, he said

it was the imperial pleasure to make taxation light. Therefore, there was

no need to conjure up an imaginary guarantor of his tailor bills. He lived

in good quarters, had three square meals a day and met his various small

accounts with unfailing regularity.

THOSE who recall Emperor Norton only in his old age, when he was stoop-shouldered, rather wabbly on his pins and presenting a woebegone appearance in general, may not realize that when the hallucinations first took possession of him, and for years afterward, he was quite a figure of man. He was tall, well-built, with a grave and stately mien that offered no suggestion of mental weakness. On any common topic he was sane enough. It was only when he opened up on the subject of imperialism that his wits went astray, and even then his talk was not disconnected or scattering.

To the best of my knowledge and information, Emperor Norton was the only potentate who had a consistent good time from start to finish. He had all the crcumstances of power without the worry. Governors, Congressmen, Mayors and policemen were only so many spokes in the wheel of his administration, and as he pronounced them a serviceable lot he never interfered with the ordinary discharge of their duties. He issued numberless proclamations, passed them along the line with a proper sense of dignity, and let it go at that.

EMPEROR NORTON'S nature was eminently conservative. Every kind of agitation afflicted him as a blow at royal prerogative. He was deeply concerned over the Denis Kearny movement; and the new constitution that followed it he denounced as equivalent to high treason. He watned to burn the obnoxious document, but under modern restraints, he wished Hall McAllister, the big attorney, to clear the legal way. But, as a rule, his life was unruffled and serene. He never could say too much about the loyalty of his subjects. What was, perhaps, more to the point, he never made himself a nuisance. He knew where to find the leading men at leisure hours, at luncheon and the like, when his presence only gave an opening to good natured jocularity.

The Emperor was deeply interested in higher education. When the University of California, in 1873, moved from the old barracks in Oakland to its new home in Berkeley, Norton I was not an infrequent visitor to those classic shades. His visits were the occasion of unbounded enthusiasm, sometimes approximating a riot. I know whereof I speak, for I was an undergraduate participant in these celebrations. His Majesty was a bit perplexed at the noisy character of the demonstrations of loyalty on the part of the student body, but soon became reconciled, and often said that we were the most satisfactory of all his subjects.

ON ONE occasion Dom Pedro de Braganza, the last Emperor of Brazil, arrived in San Francisco on a tour around the world to gain knowledge for the benefit of his people, who later on ungratefully drove him into exile. His chief aim was to study the various institutions of learning and at the invitation of President Gilman, His Imperial Highness visited the University of California. There was quite a formal reception in the assembly hall. President Gilman and the Emperor of Brazil were the central figures. Around them were ranged the college dons and various local dignitaries. Just as things were settling down to business, Emperor Norton breezed in. It happened that there was an empty seat on the platform. The temptation was too great to be resisted. Some of the young highbinders pointed out the seat to our Emperor, and whispered it was reserved for him.

Norton I was more than commonly resplendent. His uniform was new, his silk hat decorated with gorgeous plumage. I don't know what the real thing thought as the old chromo marched on the platform and took his seat. To the credit of our common humanity, be it said, nobody laughed, although a big room full of people were on the hair-trigger edge of a mighty explosion.

President Gilman whispered an explanation to the Brazilian monarch, who seemed to be mightily amused, and later in the day the two Emperors met, with mutual and distinguished consideration.

NORTON

I always took very seriously his position and responsibilities as one of

royal stock. He kept fairly well posted on the movement of the kingly

class,

especially as to the record of births, deaths and marriages. He always

took official notice of these joyous or mournful events, and probably

every

sovereign in Europe received some kind of communication, written on the

letter-head of the Emperor of California. He was deeply shocked when

Napoleon

III lost his throne, and wrote him a touching letter of sympathy. When

Napoleon died a little later Emperor Norton donned a mourning emblem and

offered his widow, Eugenie, an asylum in California.

NORTON

I always took very seriously his position and responsibilities as one of

royal stock. He kept fairly well posted on the movement of the kingly

class,

especially as to the record of births, deaths and marriages. He always

took official notice of these joyous or mournful events, and probably

every

sovereign in Europe received some kind of communication, written on the

letter-head of the Emperor of California. He was deeply shocked when

Napoleon

III lost his throne, and wrote him a touching letter of sympathy. When

Napoleon died a little later Emperor Norton donned a mourning emblem and

offered his widow, Eugenie, an asylum in California.

THE old man had a couple of strange companions. D.O. Mills, the great banker, owned a fine dog, with highly aristocratic antecedents. As a rule, a dog is wide awake to the main chance and seldom changes masters, except for good and sufficient reasons, even hanging on to a bad bargain with a fidelity that challenges at once human wonderment and admiration. Why a dog, with a well-balanced mind, should have thought it expedient to desert D.O. Mills for Emperor Norton is one of the mysteries of canine nature with which I do not purpose to grapple. Let is suffice to state the fact. The D.O. Mills quadruple attached himself to his Imperial Majesty, and evidencing, moreover, a penchant for saloons with free lunch-counters, together with a general "lazzaroni" disposition, nothing could be more appropriate and natural than the name "Bummer," which he received by universal consent.

Bummer, in the course of time, acquired the opulent and supercilious manner inseparable from good living, and, in due season, he, too, gathered in a dependent on his prosperity. A sad-eyed, despondent, broken-hearted dog became his familiar. He never presumed to interfere with the feasts set before Bummer, but when his superior's appetite was sated the melancholy canine gobbled up eagerly the remaining crumbs. By a common inspiration this lean and hungry dog was christened "Lazarus."

EMPEROR NORTON and his companions, Bummer and Lazarus, were among the notables of San Francisco for many years. You could see them any day on Montgomery street, the Emperor in the lead, with his weird, snaky cane under his arm, Bummer close behind and Lazarus, the plain dog, inheritor of of [sic] many bars-sinister, bringing up the rear at a respectful distance. Those were the last of the gold days—that proceeded the age of brass.

The old Emperor did not die too soon. His faithful friends, Bummer and Lazarus, had gone the way of all flesh, canine or human. The remaining pioneers were few and far between. A rising generation had come to think of him more as a clever imposter, rather than as one unbalanced by a cruel blow of fortune. His health was breaking badly. He was neglectful of his person. From being a monomaniac he was drifting rapidly into a condition of complete mental decay. But again fate interposed mercifully. As he neared the point where he was doomed to become a public charge he suffered a stroke of apoplexy in the streets, which proved fatal in a few hours. That was in the fall of 1879. In his room was found a bundle of currency for 1880—the year that never came, so far as His Imperial Highness was concerned.

IN the noble collection of Californians which Mr. G.H. Barron, curator

of the Park Museum, has been collecting for twenty years past, and which

constitute a history in itself, are to be found many personal and literary

mementos of the Emperor. These will best illustrate how strong a hold this

strange person had on his day and generation, and will also throw a

pleasant

light on the character of the pioneers, whose kind deeds and thoughts

lightened

the heavy burdens of adversity.

Mr. Wilkins personally knew all his characters and, so, writes from

a vantage ground. Each of the articles will be complete in itself.