Under the Code in the Old Mission

Under the Code in the Old Mission

by

Walter J. Thompson

by

Walter J. Thompson

There are two phases of remembrance connected with the Mission district which appeal forcibly to the old-timer. They have no direct clinch of attraction to the newcomer outside of the glamour of romantic interest attached to the section through a general knowledge of its history and development as handed down by writers and gossips.

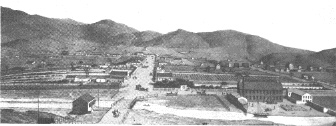

The first phase is of a nebulous formation and is made up of what he recalls of events that transpired when he was very young and before the footsteps of the padres had been entirely obliterated from El Camino Real and when the Mission was a suburban pleasure ground for the residents of the city. It was there that the amusements of the time were staged in a big array of variety. The dreamy quietness which hung over the place and which was made so much of by Bret Harte and other impressionable personages, and which had clung to it ever since the coming of the fathers and the founding of the Mission Dolores Church in 1776, had departed. It was, however, a spot fair to look upon, with fields of flowers basking in soft sunshine around the old adobe residences of the Spanish families and other buildings, and with vistas of green willows marking the spots where the creek waters ran. Birds trilled their lays on every hand and the pall of gray fog that haunted the sandy wastes westward of the city never reached that region. So the gringo found the old Mission and he immediately set up his amusement tents.

Soon were there two plank roads connecting it with the city, one along the Mission road, starting from Happy valley at Montgomery street, and the other winding a sinuous way through St. Ann’s valley and by Yerba Buena Cemetery, close by the present Civic Center. Along these roads ran the busses bearing loads of merry amusement seekers. There was no Sixteenth street then—it was called Center street, and was a wide thoroughfare from the Mission road to the old church facing the plaza at Dolores street. Besides the bear and bull arena close to the church and near the Mission road, were two race courses. They were fairly good racks and numerous were the equine speed contests that were pulled off there. Bill Shear, a popular boniface of the day, kept the noted Nightingale at Center street, and the road, and a short distance away was the well-known Willows. Other roadhouses were scattered about in charmingly picturesque profusion, and there certainly was always a “lot-doing” in the amusement line. . . . No interference was there with the wild whirling of the wheel of chance by officious policemen. No halt was there called in the display of exuberance in the race for enjoyment whatever angle it might take, and it can be said in all fairness that the pioneers did not reach a pitch of extravagant license.

There was one feature of that old Mission life that lurks in the old-timer’s memory wrapped in a robe of awe that yet awakens with serious faces and lowered voices the tragedies of the code of honor that took place there. According to these legends the pop of the pistol was frequently heard among those willow copses and several spots were pointed out which were almost as famous in local annals as any around Bladensburg’s blood-stained turf.

The code of honor was in a discredited condition in many parts of the world when gold was discovered in California. Men were beginning to realize that they had a right to hold opinions antagonistic to their neighbors without being called upon to have their appetite for a matutinal meal spoiled, probably for good and all, by backing up those opinions at the muzzle of a frowning pistol. Yes, the code was beginning to lead a back-alley existence when some hot-blooded admirers picked it from the gutter, furbished up its impressive title and lugged it from scene of its ignominy far across mountain and plain and overseas to this new land with its new population and its new methods of life. For awhile it found a resting place where existing conditions were in accord with all the traditions of its bellicose past. Here was a spot where manhood was reveling in its pride of strength, its arrogance of power, its lust of gold. Life was a whirligig. Each man was a law unto himself at the beginning, and if there was a semblance of right governing his dealings with his fellow man it was but the thin skin over the hard muscles of might. The charter of the new land was based upon the pistol and bowie knife and men’s passions in every walk of life often slopped over the brim of Reason’s bowl until human life was held cheaper than the yellow metal for which they schemed and worked.

For ten years the code held sway and among its votaries and victims were some of the best and brightest citizens of the town. Early in the its tumultuous career the code was divided into two divisions—the high and low degree. The code of high degree was the duello, with all the punctilious ceremony that was its own in the palmy days of yore. More democratic methods prevailed as to the low degree. It was a case of passing an insult, then drawing a gun to avenge it, and the man who drew first and was quickest with the trigger won out. The low degree code did not survive the first vigilance committee, organized in 1851. It was quickly regulated out of existence. But the code of high degree held on, encouraged by a certain clique in the community that considered it the only way to settle differences between gentlemen. Thus the Mission came to be reckoned as the place to settle these differences, and many were the parties that escorted two belligerent gentlemen out the Mission corduroy road and saw to it that in some secluded nook one or both of the pair received a bullet puncture, which, whether fatal or otherwise, was reckoned as a token of satisfaction according to the code. If death attended the meeting a funeral followed, but seldom an investigation. No record was ever known to be kept of these Mission duels, but during the early fifties they numbered a score or more. There was several downtown rounders and also habitues of the Nightingale who could count them off on their fingers and give names and dates and results. No affair could be pulled off without their knowledge, and if they did not attend they soon had all the details of the encounter. These knowing ones could tell you of many an unmarked grave out in the Mission willows, and they could tell of encounters between two combatants with no witnesses and whose bodies had been found, each with a bullet hole in the heart. The Nightingale was often a stopping place for combatants on the way to the field of satisfaction. Frequently would they line up at the bar, each duelist at an end of the counter and with mutual friends between, and absorb a drink or two before proceeding on their way to the battle ground. At those times not a word was spoken of the purpose of their journeying and an ordinary observer would set them down as a party of gentlemen out on a little enjoyable spree. No sign was observable either to tone and manner of the bitter feeling that rankled in the hearts of the prospective combatants and which each felt could only be abated by the death of the other. Nor from the cheerfulness or demeanor that swayed those two men would one get the impression that they were on serious business bent and that they realized that perhaps within an hour that golden sun just peeping through the mists of the east would look upon their corpses staring blankly in the morning sky.

One of these Mission duels had its provocation in the Nightingale. It was between two gamblers, “Curly” Dan and Joe Mendoza. Both had come down from the mining camps of the American river with considerable loot won from miners at the enticing game of monte, which both could play to perfection. After a long session at bucking the tiger at the El Dorado, in which fortune had played them scurvy tricks despite their cunning, these two cronies of the cards, in ugly mood, landed at the Nightingale and proceeded to pour libations of fire water into their systems. The ugliness of their moods increased and soon by the course of argument, the lie was passed, allowed by an attempted blow by Mendoza. “Curly” reached for his gun, and there would have been a low-degree affair then and there, but Boniface Shear interposed with a warning that his place wasn’t a shooting gallery. And Bill Shear was somewhat of a determined character himself, and when he gave a warning it was just as well to take notice of what he said. Both gamblers knew that. So “Curly” hissed out: “You don’t dare follow me.” “Follow you any where and any time,” retorted Mendoza, “and you’d better start right now.” As the two angry men passed out, “Curly” looked around and said: “We don’t need any help in this, so you fellows mind your own affairs.” It is to the credit of the Nightingale bunch that they did mind their own business and betrayed no inquisitive spirit. The next day the body of “Curly” Dan was found up along the line of Seventeenth street, a bullet in his heart. Mendoza never came back. As there was every indication that “Curly” had been shot from the front and that, as his gun showed, he had had a shot at his opponent, no search was made for him. “Curly” Dan’s funeral was quite a big one.

Grim tragedy did not prevail at all of these Mission duels. Often there was a serio-comic side to them. For instance, there was that affair involving William M. Gwin, United States Senator, and the haughty head of the chivalric element of the Democratic party. He had a dispute to settle with another prominent citizen, one J. W. McCorkle. They decided upon rifles at thirty paces, an agreement which should properly, with good marksmanship, have resulted to both being laid out. An exchange of shots was had in the little glade wherein they met without damage being done to either party, and mutual friends effected a reconciliation. But things were not all right by a jug full. Even as they shook hands an irate man jumped into the arena and wanted to know what all the shooting had been for. “Cause,” said he, “I want to tell you you’re a bum lot of marksmen and somebody has got to pay for my mule that’s lying dead over there.” The mule was there, sure enough, and it was dead. So Gwin and McCorkle tossed a coin to see which should pay for the mule, and Gwin lost. Everybody returned to town in rare good humor. Another affair that threatened to have a most grewsome tragical ending wound up a comedy owing to the antics of an odd character known as “Huckleberry Joe,” who was well known in all downtown resorts and roadhouses everywhere. Two sports of the kind that afterward left town to avoid complications with the vigilantes had a falling out and a challenge followed.

They made a special agreement by which each was to have a choice of weapons. One favored a bowie-knife contest and the other a pistol affair. It was settled that each should have one shot, and if nothing came of the exchange of lead they should fall to with bowie knives. Great secrecy was maintained over the matter, and only a few of their closest friends were let in on it. The contest was set for a vacant space on the outer southern edge of the Mission, and all parties were on hand promptly. The shots were exchanged and neither bullet found a billet. Then, with hate-distorted faces, the two men sparred around each other with long-bladed bowies in their right hands. It was looked upon as a duel to the death. Suddenly there was a wild whoop and a man dashed into the open space from the chaparral. It was Huckleberry Joe, whom everybody knew for his dislike for work and his ability of living at the expense of his friends, as well as for a flowery vocabulary that would have been the making of a dozen poets. Right among them he dashed, crying: “Scoot, ye fragrant daisies and dew-bespangled buttercups. The bull bitin’ is a-pourin’ out after ye, an’ the tread of their hoofs is like a herd of bufflers. Scoot, I tell you. It’s hanging’ if they git ye.”

No one knew what was coming off from this disjointed warning, but Joe’s excitement seemed real, and several of the party had no fancy for falling into the hands of the authorities. So the scooted, every one, the combatants leading the way. Later it developed that the flowery-tongued one had been hired to break up the affair and he had been successful.

The Mission narrowly missing being the scene of the famous Broderick-Terry duel, which marked the collapse and passing of the code in California. It was fought out near Lake Merced. But the blood trail of the code left its impress upon Mission history.

There are other and more pleasant things attached to the other phase of retrospect which the old-timer may prefer to remember. He likes to think of the Mission, perhaps, when the willow copses were cleared away and the old steam dummy train gave way to the street cars, with the merry jingling bells on the horses’ necks; of the passing of the corduroy roads in favor of the well-laid-out streets, lined with pretty, garden-surrounded homes. He likes to recall the days of that paradise of picnickers and amusement seekers, Woodward’s Gardens; the days of the big recreation park, where giants of baseball of that halcyon period fought their mighty battles; he likes to let his thoughts dwell upon old Red Rock, that trysting place of Mission swains and their fair companions upon sunny afternoons and moonlight summer evenings; and also to recall happy hours when the night air resounded with the melody of “The Spanish Cavalier” or “When the Leaves Begin to Fall,” or “Mollie Darling,” as some Mission troubadour threw all the feeling of his heart into his arms and fingers as he manipulated an accordion or a concertina for the delectation of his fair one.

How old melodies trickle through one’s memory and cast a soothing spell over all!