Care Free San Francisco

By Allan Dunn

Care Free San Francisco

By Allan Dunn

Before

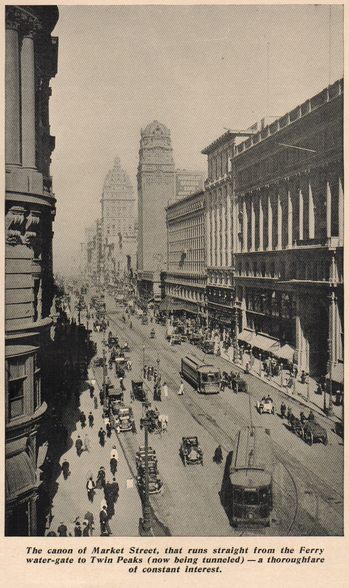

the fire, when cable cars clattered up Market Street, that thoroughfare

divided the city into two parts, and one was born and raised "north" or

"south of the slot," and thus classes as artistocrat or plebian. The "slot

southron" was of the horny-handed, tougher type of humanity; his district

was of the Bowery order. To the north the homes of the classes with more

money and more leisure fringed the down-town commercial district and climbed

Nob Hill, while the higher they climbed the more they literally "looked

down" upon those of the lower levels. The entire waterfront, as ever in

a seaport town, had its fringe of the humanity that go down to the sea

in ships. Telegraph Hill was then, as now, the Latin Quarter, close neighbor

to Chinatown, and both fringing Russian Hill, still the Art Colony—a Bohemia

of all orders, from the artistic to the rough-and-ready. This portion is

unchanged, but Market Street, though the main artery of the city, is no

more the dividing line.

Before

the fire, when cable cars clattered up Market Street, that thoroughfare

divided the city into two parts, and one was born and raised "north" or

"south of the slot," and thus classes as artistocrat or plebian. The "slot

southron" was of the horny-handed, tougher type of humanity; his district

was of the Bowery order. To the north the homes of the classes with more

money and more leisure fringed the down-town commercial district and climbed

Nob Hill, while the higher they climbed the more they literally "looked

down" upon those of the lower levels. The entire waterfront, as ever in

a seaport town, had its fringe of the humanity that go down to the sea

in ships. Telegraph Hill was then, as now, the Latin Quarter, close neighbor

to Chinatown, and both fringing Russian Hill, still the Art Colony—a Bohemia

of all orders, from the artistic to the rough-and-ready. This portion is

unchanged, but Market Street, though the main artery of the city, is no

more the dividing line.

South of it now are manufactories, the railroad yards, cheap hotels and a melange of Greek and Servian restaurants, boarding-houses and amusement places. Its original population has drifted south into the district of the Mission and down the peninsula, into a healthier form of living, rearing a sturdier generation.

The so-called poorer classes live under happier conditions here. You can't submerge a "tenth" in an out-doors land, and foraging is easy in a climate where ice in summer and coal in winter are really luxuries, never necessities. There is no anemia and little indigence. The gum-selling, match-vending urchins of the Rooseveltian families of the Latin Quarter are full-cheeked, round of limb, with stomachs well lined with spaghetti. Even sleeping out in a barrel or a box loses its terrors where King Frost owns no realty. Blue noses, shivering limbs and chilblains leave the most unfortunate alone. The streets are an everyday playground, and there are parks everywhere, from Golden Gate, with its fifteen hundred verdant flower-set acres to Portsmouth Square, set between Chinatown, the Italian Quarter and the darker places of the city.

Nob Hill, with its homes of the wealthy, remains, though many of the owners have supplementary country places in the southern suburbs. There is a gap, partly filled by apartment houses, where the dwelling houses once joined the down-town business district, but far out to the west, across the breadth of the city, stretches the residence district, and southward, past the Mission by aristocratic Burlingame, Menlo Park and Redwood City, bungalows humble and elaborate alternate with palatial country estates.

Take

your right hand. The extended thumb well represents the peninsula at the

head of which, on the nail, stands San Francisco, with its growing population,

ever squeezed out downwards, past the knuckle. Between thumb and fingers

is the southern arm of the great bay. To the north the other half of this

island sea balances it with, at its upper end, the combined streams of

the navigable Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, ever combatting the saltiness

of the waters. The western shore of this northern arm curves down to make

the northern portal of the Golden Gate. The city occupies the whole nail.

In early days it was easily divided into the Presidion and Potrero with

the Devisadero (now Divisadero Street) between; the Mission and the Embarcadero,

good old romantic and yet practical names. Today, the inside of the nail

forms the main waterfront, which swings north along the rim, but mainly

faces east and the mainland.

Take

your right hand. The extended thumb well represents the peninsula at the

head of which, on the nail, stands San Francisco, with its growing population,

ever squeezed out downwards, past the knuckle. Between thumb and fingers

is the southern arm of the great bay. To the north the other half of this

island sea balances it with, at its upper end, the combined streams of

the navigable Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, ever combatting the saltiness

of the waters. The western shore of this northern arm curves down to make

the northern portal of the Golden Gate. The city occupies the whole nail.

In early days it was easily divided into the Presidion and Potrero with

the Devisadero (now Divisadero Street) between; the Mission and the Embarcadero,

good old romantic and yet practical names. Today, the inside of the nail

forms the main waterfront, which swings north along the rim, but mainly

faces east and the mainland.

Opposite, at the second knuckle of the first finger, lie the transbay cities of Oakland, Berkeley and islanded Alameda, at the foot of the Berkeley hills. By the outer corner of the nail rim is the Presidio as of yore, and the Ocean Boulevard following the outer curve. Straight across the city, east and west, runs Market Street. Twin Peaks at its end are to be burrowed through, the Panhandle of the great Golden Gate Park juts from the main grounds and ties up the Pacific Ocean with the city and the inner sheltered bay.

To feel the pulse of a city and to test its temperature, watch its streets.There are scenes of San Francisco highways so distinctive, so unique, that the memories of them never fade.

Let us take Market Street, partly commercial thoroughfare, shopping district, amusement center and boulevard. With its broad sidewalks, running to sunrise and sunset, backed by high cliffs of stone and "reinforced concrete," it has two climates, two temperatures of sun and shade. They say you can wear flannels on one side and furs on the other, which is not uncomfortably true, though people really only wear furs as they follow the season's fashions in San Francisco—for exhibition purposes, to encourage the shopkeepers and for visiting purposes to climes less favored than this,

For we only know it's Christmas by the calendar out here.

Before noon Market Street is a bustle of business men. At noon the bright-eyed blooming youth of the office forces debouche for luncheon and a "how-d'ye-do." Then come the down-town cars to discharge shopping matrons, and forth come the butterflies of leisure and of pleasure. Towards the half light the working bees buzz out again and turn drones for the hour before dinner (the five-o'clock promenade.) Playtime has commenced. Actor, soubrette and ingenue, both professional and amateur, soldier and sailor, clerk and boulevardier, workingman and workingwoman, a dozen tongues, a dozen grades of color, a dozen national costumes—miner from the desert, cowboy from the range, chekako or sourdough from Alaska; upper, lower and half world; full of the joy of being, or forming one of the lively throng, exchange greetings more or less conventional, gaze in the brilliant store windows, buy—or hope to—and go to dinner, clubward, homeward, to restaurant and boarding-place.

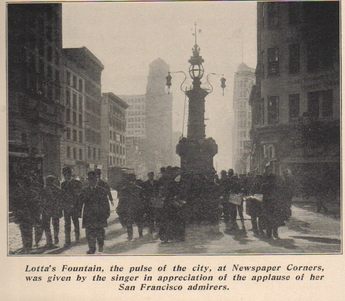

The

afternoon editions are out; Lotta's Fountain at Newspaper Corners is a

swirl of newsboys. Fans discuss the display of the final baseball scores.

Swains and flower-loving folk are buying nosegays by the Chronicle Building,

the safety stations are crowded with waiting car-riders traveling ferry

or suburb-ways, the dusk settles into night, and Market Street has its

quiet hour.

The

afternoon editions are out; Lotta's Fountain at Newspaper Corners is a

swirl of newsboys. Fans discuss the display of the final baseball scores.

Swains and flower-loving folk are buying nosegays by the Chronicle Building,

the safety stations are crowded with waiting car-riders traveling ferry

or suburb-ways, the dusk settles into night, and Market Street has its

quiet hour.

Then the lights flash out above stores and restaurants, nickelodeons and dimeodeons, dental parlors, saloons and cafes. Down town comes the throng again, and the scene of the afternoon is repeated. The street keeps lively till the theatres are closed, the restaurant tables piled, the "rabbit" editions out and the all-night cars start up their intervaled procession.

Not

always though. On Christmas Eve a hundred thousand gather at Lotta's Fountain

and listen with silent rapture and rapturous applause while Tetrazzini

or Bispham sings and Kubelik plays, managers smiling the while at the advertisement,

with no risk for voice or violin in the pleasant air. On New Year's Eve

the whole population, young and old, wedge the sidewalks, harass the police

while the parade passes, and then swarm the streets, carnival clad—a confetti-tossing,

horn-blowing, bell-ringing, shouting, laughing charivari of color and clamor.

Bands blare, and the crowd "rags" in gay abandon. Windows ablaze disclose

the older, less enthusiastic lookers-on. Sightseers from the "leisure ranks"

try to steer at slow speed through the throng and submit, laughingly, chauffeur

and passengers alike, to the chaff and confett throwing of the happy hoi

polloi. All is good humor, and "rough house" is tabu by a happy mixture

of sentiment and police regulation.Dawn wags a warning finger behind the

tower of the Ferry Building before the crowd goes home; the strings of

electrics go out, and the deserted street looks garish with its streamers

of serpentine hanging everywhere and drifts of confetti being swept up

by those unfortunate enough to have to work on New Year's morning.

Not

always though. On Christmas Eve a hundred thousand gather at Lotta's Fountain

and listen with silent rapture and rapturous applause while Tetrazzini

or Bispham sings and Kubelik plays, managers smiling the while at the advertisement,

with no risk for voice or violin in the pleasant air. On New Year's Eve

the whole population, young and old, wedge the sidewalks, harass the police

while the parade passes, and then swarm the streets, carnival clad—a confetti-tossing,

horn-blowing, bell-ringing, shouting, laughing charivari of color and clamor.

Bands blare, and the crowd "rags" in gay abandon. Windows ablaze disclose

the older, less enthusiastic lookers-on. Sightseers from the "leisure ranks"

try to steer at slow speed through the throng and submit, laughingly, chauffeur

and passengers alike, to the chaff and confett throwing of the happy hoi

polloi. All is good humor, and "rough house" is tabu by a happy mixture

of sentiment and police regulation.Dawn wags a warning finger behind the

tower of the Ferry Building before the crowd goes home; the strings of

electrics go out, and the deserted street looks garish with its streamers

of serpentine hanging everywhere and drifts of confetti being swept up

by those unfortunate enough to have to work on New Year's morning.

A great place for illuminations and display, this city. Most of the windowsills down town are set with standards, ready for flags kept stored for all emergencies. The municipal staff has an enormous property warehouse of banner-bearing poles and electrical connections. The occasion sees a systematic force moving along the main thoroughfares and leaving them wreathed and draped and festooned in a blaze of light and color. The Ferry tower and the domes and outlines of the big office buildings and hotels are always ready socketed for a chance to brighten up.

The

heart of the shopping district proper, where prices are not so much a matter

of consideration, lies north of Market Street in a district bounded by

Powell and Kearny streets, Sutter and Market. There are stores not bettered

by any in the New World, few in the Old. All the heart feminine, or masculine,

can desire of raiment or decoration, of furnishings for self or home, is

centered here, imported from afar or near, the choice of the world's choicest.

Not so many afoot here as on Market Street. The patronesses alight from

gas or electric-driven cars of every expensive, exclusive style and make.

Here fashion reigns, and the furs are ermine and mink. Your Market Street

maiden will wear white serge at Christmas if she fancies it becoming, her

admirer sport his straw in March and only abandon it in November because

the football season has commenced and vaguely he fancies it incongruous.

Not so on Post Street or Grant Avenue. The Boston bull wears an uncomfy

but swagger suit of knitted wool matched to harmonize with his mistress's

toilette and the lining of her limousine. Outside the White House, the

City of Paris, Shreve's and the like magazines of trade, stand uniformed

commissionaires, stolid and polite as the liveried chauffeurs. Here is

one phase that helps San Francisco to be fancifully named the "Paris of

America."

The

heart of the shopping district proper, where prices are not so much a matter

of consideration, lies north of Market Street in a district bounded by

Powell and Kearny streets, Sutter and Market. There are stores not bettered

by any in the New World, few in the Old. All the heart feminine, or masculine,

can desire of raiment or decoration, of furnishings for self or home, is

centered here, imported from afar or near, the choice of the world's choicest.

Not so many afoot here as on Market Street. The patronesses alight from

gas or electric-driven cars of every expensive, exclusive style and make.

Here fashion reigns, and the furs are ermine and mink. Your Market Street

maiden will wear white serge at Christmas if she fancies it becoming, her

admirer sport his straw in March and only abandon it in November because

the football season has commenced and vaguely he fancies it incongruous.

Not so on Post Street or Grant Avenue. The Boston bull wears an uncomfy

but swagger suit of knitted wool matched to harmonize with his mistress's

toilette and the lining of her limousine. Outside the White House, the

City of Paris, Shreve's and the like magazines of trade, stand uniformed

commissionaires, stolid and polite as the liveried chauffeurs. Here is

one phase that helps San Francisco to be fancifully named the "Paris of

America."

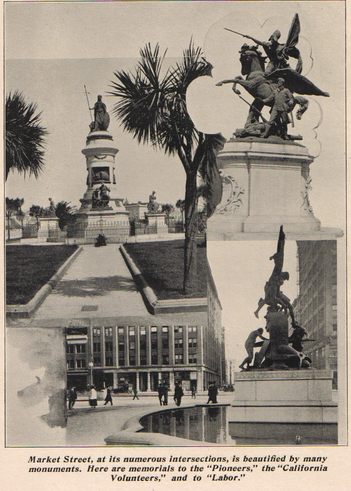

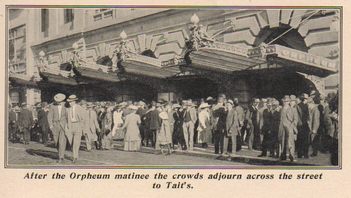

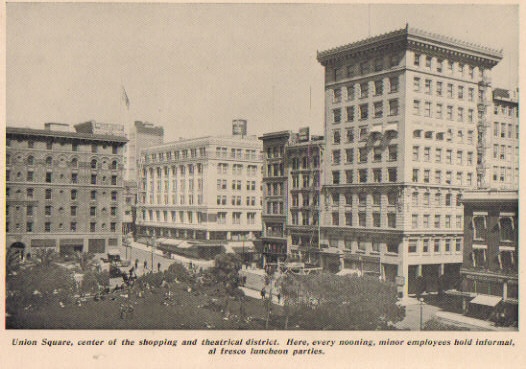

Hard

by is Union Square, a city block of verdure, palm bordered, flower bedded,

path checkered; the gray column of a graceful statue to Admiral Dewey at

its center; faced by the striking facade of the Saint Francis Hotel and

fine commercial buildings. Within two blocks are the Bohemian, Family and

Olympic Clubs, the Columbia, Cort and Orpheum theatres at hand, close to

Tait's and Techau's restaurants. It is the hub of down-town leisure life.

Its benches are always crowded, not with vagrants, but with naught-to-dos,

reading the papers, discussing politics, philosophy and what not. Not of

the wealthy class, these seat-holders; yet not of the tramp community.

Most of them are newly shaven and cleaned, their shoes are patchless, their

trousers unfringed. Bohemians in fraternity, out of work perhaps, but hopeful;

out for air probably, interested in the world in general. On seats reserved

for women are a few similars of the other sex, a maid or two with children.

Others lounge on the sunny turf, for there are no "keep off" signs here,

save one—"Loose Dogs Not Allowed"—a prohibition referring not to habits

but to liberty. No stern policeman orders idlers on. At nooning the lawns

are a pretty sight, with groups of girls and boys at picnic lunch together,

junior clerks and "salesfolk," cash girls and office boys, chumming together,

getting a real midday rest, with health and perhaps a little romance thrown

in. A kindly music-man turns loose from an upper window a flood of phonographic

melody each midday, and aids to make the place unique, delightful.

Hard

by is Union Square, a city block of verdure, palm bordered, flower bedded,

path checkered; the gray column of a graceful statue to Admiral Dewey at

its center; faced by the striking facade of the Saint Francis Hotel and

fine commercial buildings. Within two blocks are the Bohemian, Family and

Olympic Clubs, the Columbia, Cort and Orpheum theatres at hand, close to

Tait's and Techau's restaurants. It is the hub of down-town leisure life.

Its benches are always crowded, not with vagrants, but with naught-to-dos,

reading the papers, discussing politics, philosophy and what not. Not of

the wealthy class, these seat-holders; yet not of the tramp community.

Most of them are newly shaven and cleaned, their shoes are patchless, their

trousers unfringed. Bohemians in fraternity, out of work perhaps, but hopeful;

out for air probably, interested in the world in general. On seats reserved

for women are a few similars of the other sex, a maid or two with children.

Others lounge on the sunny turf, for there are no "keep off" signs here,

save one—"Loose Dogs Not Allowed"—a prohibition referring not to habits

but to liberty. No stern policeman orders idlers on. At nooning the lawns

are a pretty sight, with groups of girls and boys at picnic lunch together,

junior clerks and "salesfolk," cash girls and office boys, chumming together,

getting a real midday rest, with health and perhaps a little romance thrown

in. A kindly music-man turns loose from an upper window a flood of phonographic

melody each midday, and aids to make the place unique, delightful.

It is a parade point also, like Lotta's Fountain. Bands play here on occasions, and reviewing stands are set up. When civic weal demands, speeches are made here, and from here at times firework displays are made. It is a part of distinctive San Francisco.

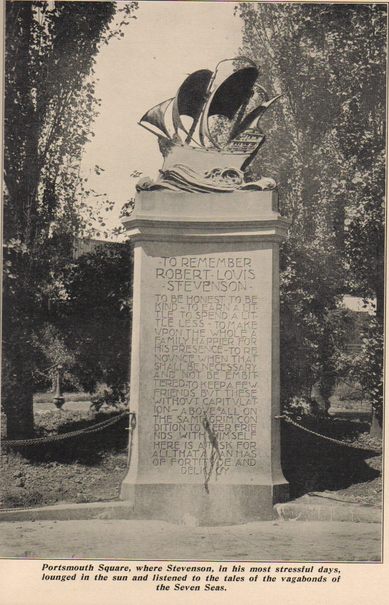

Not

very far away, nearer the bay, between upper Kearny Street and Grant Avenue,

as those streets merge into China City and Latin Town, is Portsmouth Square,

sloping towards the Hall of Justice, a place of history, with its own peculiar

loungers and its own particular monument. Once the custom house was here,

"when the water came up to Montgomery Street," a block away. Now the arbiter

of protective duties has receded harborward with the curbing of the tide.

Commodore Montgomery, of the sloop of war "Portsmouth," raised the American

flag here during the Mexican War; public meetings against lawlessness were

held here by the alcalde in the days of '49; Vigilantes hung their sentenced

criminals on the timbers of neighboring adobes; it has known barricades

and mobs, has been the scene of lawmaking and rioting in the days when

it was the Plaza.

Not

very far away, nearer the bay, between upper Kearny Street and Grant Avenue,

as those streets merge into China City and Latin Town, is Portsmouth Square,

sloping towards the Hall of Justice, a place of history, with its own peculiar

loungers and its own particular monument. Once the custom house was here,

"when the water came up to Montgomery Street," a block away. Now the arbiter

of protective duties has receded harborward with the curbing of the tide.

Commodore Montgomery, of the sloop of war "Portsmouth," raised the American

flag here during the Mexican War; public meetings against lawlessness were

held here by the alcalde in the days of '49; Vigilantes hung their sentenced

criminals on the timbers of neighboring adobes; it has known barricades

and mobs, has been the scene of lawmaking and rioting in the days when

it was the Plaza.

Facing the stately Hall of Justice, on the opposite side of the square, are the back doors of Chinatown, on either side of the dingy alleyways of the ungilded portion of the "tenderloin." A motley crowd invests the square, crosses its pathways, drinks at its fountain.

Shrill-laughing Chinese children, butterfly garbed, play American ball between the shrubberies; wornout hulks of wanderers by many lands and seas sit in the sun, boasting or railing, according to the degrees of their wrecked manhood, and above them a bronze galleon, with surging sails, tops the monument to him who knew and pitied all; humanity, flotsam and jetsam alike—a monument whereon is carved, "To Remember Robert Louis Stevenson," and, following, that sermon of sweet manliness that starts, "To be honest, to be kind—"

Then there is Van Ness Avenue, running at right angles from Market Street—most of the tributaries of the northern bank join that thoroughfare gore fashion—once a stately way of luxurious homes, now coming into a second dignity. Here the great fire halted on the eastern side, and here was set the temporary shopping district during the rehabilitation. West of it lies the better-off class residential district. On it are still some stately homes and some magnificent structures (largely recent) of religious and fraternal significance. Part of it the motor sales industry has pre-empted. At its junction with Market Street the new Civic Center is to be reared, dignified with City Hall, Auditorium, Opera House, Art Gallery, planned to be worthy of the future greatness of the city. The avenue is to be the main thoroughfare tying up the city proper with the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, and it will hold many memories to be of a dignified and pleasant boulevard.

California

Street, toiling from the Ferry through the wholesale and banking districts,

by Chinatown, up steep grades to Nob Hill, is not for the pedestrian, save

when the summit is reached. Up it clank the cable cars at safe but alarming

grades. Crowning it stands the Fairmont Hotel, copy of an European palace,

flanked by the Pacific-Union and Family clubs and the Art Institute. From

it unrolls a view magnificent. Beneath, to north and east, the commercial

city pitches to the view of gleaming bay, the shipping, the islands and

mountains of the farther shores; to the south and west shines the unsurpassed

panorama of the residential lands. Hills rise here and there, dark with

trees or brightly blocked with houses. All is checkered with light and

shade, dazzling sun against sombre masses, a fog finger stealing in from

the ocean, guided by mysterious currents; gleam of water, the sea breeze

in your face, a gull overhead, below stretching to misty horizons the City

Beautiful.

California

Street, toiling from the Ferry through the wholesale and banking districts,

by Chinatown, up steep grades to Nob Hill, is not for the pedestrian, save

when the summit is reached. Up it clank the cable cars at safe but alarming

grades. Crowning it stands the Fairmont Hotel, copy of an European palace,

flanked by the Pacific-Union and Family clubs and the Art Institute. From

it unrolls a view magnificent. Beneath, to north and east, the commercial

city pitches to the view of gleaming bay, the shipping, the islands and

mountains of the farther shores; to the south and west shines the unsurpassed

panorama of the residential lands. Hills rise here and there, dark with

trees or brightly blocked with houses. All is checkered with light and

shade, dazzling sun against sombre masses, a fog finger stealing in from

the ocean, guided by mysterious currents; gleam of water, the sea breeze

in your face, a gull overhead, below stretching to misty horizons the City

Beautiful.

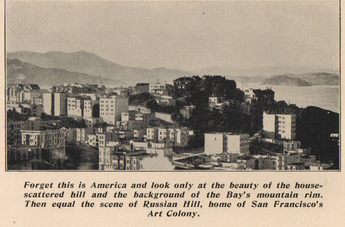

All about are the houses of the wealthy. Above Nob Hill again rises Russisan Hill, named from the forgotten, lost graves of obscure sailors buried there four score years ago. Here the view is yet more superb to reward the climber, with the vista in all rightfulness pre-empted by lovers and portrayers of the beautiful. About the artist-planned houses are terraced gardens, and though the old-fashioned homes have passed, the place is full of charm and beauty.