Care Free San Francisco

By Allan Dunn

Care Free San Francisco

By Allan Dunn

The

best part of life in San Francisco is spent out of doors. The most seductive

of repasts needs appetite, and hotels, however luxurious, are not capable

of much walled restraint where the climate laughs in at the window after

breakfast every morning.

The

best part of life in San Francisco is spent out of doors. The most seductive

of repasts needs appetite, and hotels, however luxurious, are not capable

of much walled restraint where the climate laughs in at the window after

breakfast every morning.

There be fogs in San Francisco, gentle reader. It was the fog outside the Golden Gate that retarded the heralding of the harbor until the moment was suspicious for revelation. It is the fog that fosters bloom upon the ladies' cheeks and makes velvet their skins. But it is a kindly, convenient fog. It will tone up the atmosphere all night and sometimes hang around till the breakfast dishes are cleared, but it is only done in friendly wrestle with the sun, and good-naturedly retires well before noon. Usually it stays outside the Golden Gate and beneficently charges the air with coolness. It is an equalizer of temperature, preserving an average the year around of under sixty degrees.

It has only the Golden Gate to enter through, and should it linger too late, Phoebus comes charging in his chariot and it beats a swift retreat. Mostly it is ornamental in its delay with veily wisps or floating cloaks about Tamalpais and the peaks. It helps the roses to keep blooming and the fair-greens verdant, it should never be denied, good friend as it is. It is an ally, not an enemy, as the record of over three hundred days of sunshine attests.

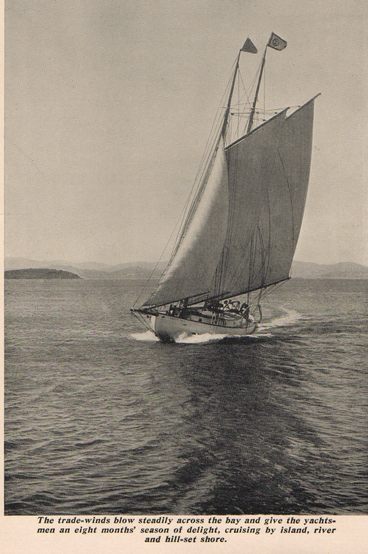

Come you to San Francisco by steamer from the Orient, or trainbound from the Occident, you enter by the water-gate, the Ferry Building, and perforce cross the Bay. I spell it with a B (and a capital one at that) because it is beautiful. Sir Thomas Lipton, who is of a surety a judge of harbors, said, at the risk of being thought unpatriotic, "It is the most beautiful Bay I have ever seen." It is, and the same is true for you. It has a thousand moods, a dozen climates. Sometimes it recalls the frowning but majestic fjords of Norway, graysea'd, windswept, high-cliffed; awesome, majestic, almost desolate. Oftener it smiles beneath blue skies, its hills checkered with gleaming buildings, forested above with the mountain summits purple as the heart of an amethyst. Verdant isles rest on its bosom, gulls are a-wing on its windways, craft of a score of flags, battleship, submarine, freighter, liner, barque and schooner, a fleet of yachts, brown lateen sails, junks of China, sampans of Japan, whalers and scow-hulled river craft; busy ferries, fussy tugs and smart launches, dazzle everywhere. It is the Mediterranean over again, with something of the semi-tropic suggestion of South American ports.

There's nothing just like it. Two great rivers, navigable a hundred miles and more, the Sacrament and the San Joaquin, send down their sweet waters to temper it, the great tides chafe about the boundaries; one shore will gleam in brightness, another loom forbidding under the passing clouds or scurrying mists. Sand dunes, tree-set hill and towering mountain rim it, with cities breaking out like an irresistible contagion everywhere.

At night the city lights invest the harbor like great diamond snakes of some djhin-jeweler. The ferry-boats are fairy boats of mystery plying between haven lights made from great rubies and emeralds. The wind sighs of lands beyond the Gate, of palm-fringed shores and pagoda'd cities, full of the lust of life and the zest of adventure. Half a dozen lighthouses wink wisely of narrow escapes and tragedies before their time. Listen, and if your mind is atune, you can hear the pulse of Progress beating steadily, day and night.

The same winds greet you on the hills, on the links, if you are a golf player, in the park, across the Presidio valleys, in the hollows of a hundred hills where iris and violet, Johnny-jump-up, lupines purple and yellow poppies of California—cup of gold—smile as you cut short their life to help your holiday. Great masses of eucalyptus, recent intruders, old oaks that defy any month to take toll on their leaves, all tell the tale of this heritage of ours, speak of its youth, abounding vitality and promise.

Come

to the Park, the fifteen hundred acres of Golden Gate, made into a garden

by the grace of God, manifested through John McLaren, superintendent, Scotchman

and master gardener. In 1870 here were shifting dunes, a waste of sand,

wind waved, desolate of herbage. Today are seventeen miles of driveways

set with trees from every clime, that open on enchanting glades and vistas

of mountain and sea. Here are lakes where wild ducks breed and paddocks

where elk and deer and buffalo graze under unconscious guardianship. The

conservatory is a rainbow of tropic blooms matched by the living splendor

of the aviary. Flowers are everywhere, luxuriant in clustering fragrance.

Old folk, families, lovers, babies, all find their charm. The children

have their swings and donkey rides in their special playground, their grizzly

bears and other strange beasts of the Zoo, and their sand bed games; the

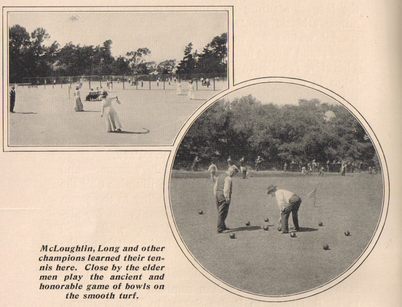

young men and maidens use the tennis courts whence national champions have

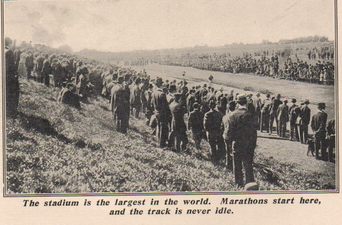

issued. There is baseball for the young, bowls for the old, the largest

stadium in America for marathons or minor athletic events, a course for

speedy horses, special waters for model yachtsmen, and a great stone stand

where music for the million is dispensed. The view from Strawberry Hill,

above Stow Lake, takes in the Golden Gate, with Tamalpais beyond, the Berkeley

Hills, the loom of Mount Diablo and, closer, the Cross on Lone Mountain.

Below, on the bridged and isleted lakelet is the Japanese tea house in

its quaint garden, a bit of Chrysanthemum Land inlaid in the great play

table of the Park.

Come

to the Park, the fifteen hundred acres of Golden Gate, made into a garden

by the grace of God, manifested through John McLaren, superintendent, Scotchman

and master gardener. In 1870 here were shifting dunes, a waste of sand,

wind waved, desolate of herbage. Today are seventeen miles of driveways

set with trees from every clime, that open on enchanting glades and vistas

of mountain and sea. Here are lakes where wild ducks breed and paddocks

where elk and deer and buffalo graze under unconscious guardianship. The

conservatory is a rainbow of tropic blooms matched by the living splendor

of the aviary. Flowers are everywhere, luxuriant in clustering fragrance.

Old folk, families, lovers, babies, all find their charm. The children

have their swings and donkey rides in their special playground, their grizzly

bears and other strange beasts of the Zoo, and their sand bed games; the

young men and maidens use the tennis courts whence national champions have

issued. There is baseball for the young, bowls for the old, the largest

stadium in America for marathons or minor athletic events, a course for

speedy horses, special waters for model yachtsmen, and a great stone stand

where music for the million is dispensed. The view from Strawberry Hill,

above Stow Lake, takes in the Golden Gate, with Tamalpais beyond, the Berkeley

Hills, the loom of Mount Diablo and, closer, the Cross on Lone Mountain.

Below, on the bridged and isleted lakelet is the Japanese tea house in

its quaint garden, a bit of Chrysanthemum Land inlaid in the great play

table of the Park.

The Presidio, heavily forested with eucalyptus sheltering its open places, great guns embanked, players on the links, soldiers on the parade ground, gives a delightful walk. The sea fringes it and the view is magnificent. Motorcars are allowed and the street cars enter one of its gates.

This same car line, that of Union Street, runs up and down the fringe of hills that mount from the northern shore and winds up at the Ferry Building. It looks down upon the water site of the Exposition and across Alcatraz to the low mountains of Marin, topped by Tamalpais, it skirts Russian Hill and skims through the Barbary Coast to the waterfront.

Here, if you find imagination good company, walk the length of it. What a heterogeneous mass of shipping. The fishing boats, army transports, freighters, oil tankers and mail liners of the Pacific bound for Panama, for Hawaii, for Australasia and the Orient; lumber ships, deck laden, from the north, a lumber raft maybe, river steamers and bay ferries, launches galore, ship, schooner, barque and barkentine in steam or at dock, loading, unloading, being scraped and painted and overhauled. Whalers, a treasure-hunting schooner outfitting, a copra carrier from the South Seas, boats of the police patrol, fire boats, ships of the lighthouse service and fish commission, quarantine and custom tugs, shore boats and launches of the cruisers and battleships sure to be in in naval row; and the strange mixture of mankind that serves them all. To walk the docks is to find in workmen and loungers the characters of a whole month's issue of those magazine that specialize on adventurous fiction. From the warehouses come subtle smells that conjure up tales of Stevenson and the Swiss Family Robinson and visions of Oriental ports. It is a fascinating world of its own, bounded by so-called snuggeries and saloons set in dark streets that after nightfall are best left untrod—the real Coast of the High Barbaree, where clubs are trumps, where they

To

the motorist San Francisco out-of-doors gives many opportunities. The old

Camino Real, the King's Highway, ran northward, a day's journey at a time

from San Diego, mission by mission, ending at the Mission Dolores, San

Francisco. It is pleasant journeying, starting by the beach boulevard,

to turn southwards toward San Jose city, fifty miles away, center of the

orchard-covered Santa Clara Valley. The way lies through constant suburbs,

by palatial estates, by country clubs, by humbler dwellings, all flower

set, tree shaded, and the return can be made easily by looping the trip

with the Hotel Vendome at San Jose as center of your curve and returning

by orchard and through more miles of civic environs to Oakland and back

by ferry. Close to San Francisco are the beautiful lakes of the water system,

bounded by a road that leads through verdant hillways to old-time fishing

villages. The motorcar can be shipped also on the river steamers to Sacramento

in preparation for a glorious day's run to Lake Tahoe, a mile up in the

Sierra.

To

the motorist San Francisco out-of-doors gives many opportunities. The old

Camino Real, the King's Highway, ran northward, a day's journey at a time

from San Diego, mission by mission, ending at the Mission Dolores, San

Francisco. It is pleasant journeying, starting by the beach boulevard,

to turn southwards toward San Jose city, fifty miles away, center of the

orchard-covered Santa Clara Valley. The way lies through constant suburbs,

by palatial estates, by country clubs, by humbler dwellings, all flower

set, tree shaded, and the return can be made easily by looping the trip

with the Hotel Vendome at San Jose as center of your curve and returning

by orchard and through more miles of civic environs to Oakland and back

by ferry. Close to San Francisco are the beautiful lakes of the water system,

bounded by a road that leads through verdant hillways to old-time fishing

villages. The motorcar can be shipped also on the river steamers to Sacramento

in preparation for a glorious day's run to Lake Tahoe, a mile up in the

Sierra.

There are numberless excursions through picturesque Marin County, through vineyarded Napa and Sonoma, up to the waters of Lake County, about Mount Diablo, all trips over good, well-defined roads—ventures of a day or two at most, with pleasant hostelries to tempt extensions.

Golf has been lightly touched upon. To the enthusiast there are many opportunities at hand, and it is a year-round sport. The San Francisco Country Club at Ingleside has a course in many respects ideal, with natural hazards, springy turf on the fair greens and a view of the ocean at every resting place. The Presidio reservation links, open to the public, but upheld by a club, has a sporty range of full eighteen holes and great scenic beauty, overlooking, as it does, the Golden Gate. Across the bay in the Piedmont Hills is an almost perfect course and a beautiful clubhouse. Rewards are plentiful for the steady, but difficulties rife for him who fails to play straight. Down the peninsula are the well-kept links of the Burlingame and Menlo Park clubs, and in Marin County the greens of San Rafael, all easy of access.

For those who love the water, there are four or five yachting organizations, led by the San Francisco and Corinthian Clubs, with a fleet of schooners, sloops. yawls and launches that keep in commission eight months of the year, some of them all year. The bay, though tricky to sail by reason of current and tide-rip, is a delightful pleasure ground, and invites the planning of a series of ferry and boat trips—to Sausalito, Belvedere, to Mare Island Navy Yard, to Yerba Buena with its Naval Training School, Alcatraz with its prison, or up the rivers to Sacramento and Stockton.

Rodmen and gunmen can find good sport in season. There are salmon in the bay and outside the heads, striped bass in estuary and slough, black bass in river and lake, steelhead in lagoon and river, and rainbow a-plenty in a score of coast streams. Ducks and geese are plentiful and, while most of the ground is preserved, there is plenty of open water. Close by, too, are deer and dove and quail.